By Paul Tomkins.

A study in the implications of the “new rewards” of the Premier League era.

Whether you are a traditionalist, a modern fan, or a mix of both, the truth is this: being in the top four matters. This is now a fact.

That 2nd to 4th used to be almost irrelevant – that it used to be “nowhere”, to paraphrase the old Liverpool quote – is neither here nor there.

The value of prizes and trophies in football is not constant. Unfortunately, money – and not just heritage – drives the importance of competitions. For instance, if £1billion was to be awarded to the winners of next season’s League Cup, the competition would be taken a hundred times more seriously by all the big clubs. The problem is, the League Cup, for all the satisfaction in winning it, is fairly irrelevant, therefore no-one will bother to attach such a prize to it. In 2011, the winners got £100,000. The difference between finishing 16th and 17th in last season’s Premier League was £800,000. Indeed, simply for finishing bottom of the Premier League in 2013/14 the reward will be £60m.

Now, I think fans of all clubs outside the top four, if they are aware that there’s a good chance a cup run will harm league form, would accept finishing one place lower if a trophy came as a reward. But when a minor trophy comes at the expense of tens of millions of pounds – which teams in the top four will benefit from as an advantage over the rest, and teams in the Premier League will benefit from over Championship sides – then it gets serious. That money offers the chance to buy far better players, and of course, clubs in the Champions League are more attractive than those who aren’t, and clubs in the Premier League are more attractive than those in the Championship.

It’s logical. Players want to join clubs in the Champions League; they’re not really drawn to the winners of a domestic cup, as enjoyable as winning a domestic cup can be. You might be able to tempt them, as City did, by paying Champions League wages before they were even in the Champions League, but then they knew they could fall back on billions of pounds if they fell short. They knew that within a few years they’d get there, one way or another. Liverpool could attract Champions League players if the club did what City did a few years back, and what Monaco are doing now: namely, paying players over £200,000 a week. But Liverpool don’t have the cash riches to fall back on.

Since the turn of the millennium a total of 28 domestic cups (14 FA Cups and 14 League Cups) have been won. In total, 17 of those were won by teams who finished in the Champions League places that same season. Perhaps you’d expect that, as they’re the best teams, but it’s still a whopping two-thirds. Three more trophies went to teams who’d been in the Champions League within the previous two seasons (Chelsea in 2000, and Liverpool in both 2003 and 2012), taking it up to 20 out of 28 “Champions League” sides, or 71.4%.

(Six of the remaining eight trophy wins went to clubs no longer in the top flight: Leicester, Blackburn, Middlesbrough, Portsmouth, Birmingham and Wigan.)

In the 21 seasons prior to the launch of the Premier League, the chances of a team who finished in the top four also winning a domestic cup was just 35% (seven of 21 FA Cups, eight of 21 League Cups). Basically, it has risen from one-third then to two-thirds now.

Now, are these clubs winning trophies because they’re in the Champions League (and its virtuous cycle), or is it because their wealth is already so far ahead of the others that they had an advantage anyway? Perhaps it’s a bit of both. I certainly don’t have all the answers, but it’s an interesting question all the same. Money buys the better players, and the better players all but guarantee better income.

Between 1970 and 1992, the average league finishing position of the FA Cup winner was 8.6, with eight teams from 10th or below winning the trophy, two of whom were from the second tier. Between 1993 and 2013 it was down to an average league finishing position of just 4.5, and but for Wigan’s triumph in May, it would read 3.8.

It’s a similar, if less dramatic, story with the League Cup. The 1970-92 average was 9.4, the 1993-2013 average 7.0. Three times in the earlier period a team from the second tier won the cup; whereas the lowest-ranked team to lift the trophy in the Premier League-era was Birmingham, at 18th. Since it was launched, no-one outside of the Premier League has won the FA Cup or the League Cup, whereas five clubs managed it between 1973 and 1992.

Only four times out of the 42 main domestic finals during the past 21 years has a team that finished lower than 11th in the top division won one of the those cups (9.5%). And yet it happened 12 times during the previous 42 finals (28.6%). In other words, the chances of a club below mid-table winning a trophy (if we say 11th is mid-table) has withered from one-in-three to one-in-ten. The Premier League appears to have made its participants stronger, just as the Champions League makes its participants stronger still.

Perhaps this is all a case of stating the obvious – money breeds success – but sometimes it helps to go over the data.

Prizes

The two best prizes have for many years been the league title and the European Cup, although probably up to the ‘90s the FA Cup was seen as a premier cup competition, because of its age and history. Young fans might be surprised to discover just how valued the FA Cup was; some past generations say that it even trumped winning the league.

The Premier League’s money-oriented evolution has helped see to that. The FA Cup is no longer especially important. Whether you like it or not, it’s true.

If you want to know how important something is, measure it by the desire to cart it through the streets in an open-top bus.

Of course, you also don’t parade finishing 4th around the streets of your city or town. But clubs don’t really have open-top bus parades with the League or FA Cup, either. Not any more; not unless they’ve never won anything before. However, you would parade the Champions League trophy around the streets. And finishing 4th, as Liverpool did in 2004, unlocks the gates to a potential Istanbul. Winning the League Cup, in this day and age, does little.

Another way to judge a competition is the strength of the XIs selected for it. While you may get rotation in the league, seriously weakened sides are only fielded in extreme circumstances, usually towards the end of the season when nothing is in the balance. And it only happens in the Champions League if the tie or the group is already won.

However, the domestic cups, and the Europa League, are different. The League Cup has become a quasi-youth competition for the major clubs, and therefore if you beat Manchester United or Arsenal you’re not really beating their proper side; and if someone else has already beaten their weakened side then that just means that the competition wasn’t as strong as it could possibly be. Of course, sometimes a second string XI will be more motivated, and/or less fatigued. But it’s still not like facing a highly motivated, strongest XI.

It used to be just Champions League clubs who fielded shadow sides in the cups, but it has recently become any club fearing relegation (which can mean from mid-table downwards), plus teams seeking promotion to the top flight. So the strength of the competition is yet further diluted.

There’s clearly a distinction in terms of the number of domestic cups won by the following three specific bands of teams: first, those who qualify for the Europa League, perhaps having attempted to make the top four; second, those who finish mid-table; and finally, those who get relegated.

The teams who finish 5th, 6th and 7th are clearly better than those who finish between 10th and 14th. Yet since the start of 1992/93, the teams who have finished in those higher three positions (21 seasons x 3 league positions = 63 “teams”) have won a domestic cup only three times (4.8%). And yet the teams who have finished in those five “mid-table” positions (21 seasons x 5 league positions = 105 “teams”) have won the domestic cups on eight separate occasions (7.6%).

Meanwhile, no team that has narrowly escaped relegation (finishing in the four spaces above the bottom three) has won a domestic cup in the Premier League era, and yet twice (both in the last three seasons) a club possibly expected to avoid relegation won the League Cup (in Birmingham’s case) and the FA Cup (Wigan), only to find themselves demoted to the Championship.

Indeed, in the last 13 seasons, as the importance and influence of the Champions League has grown, there seems to be a kind of exclusion zone from 12th down to 17th, where clubs have focused on Premier League survival, and achieved it without adding to their trophy cabinet. Perhaps this shows that they placed little importance on the cups?

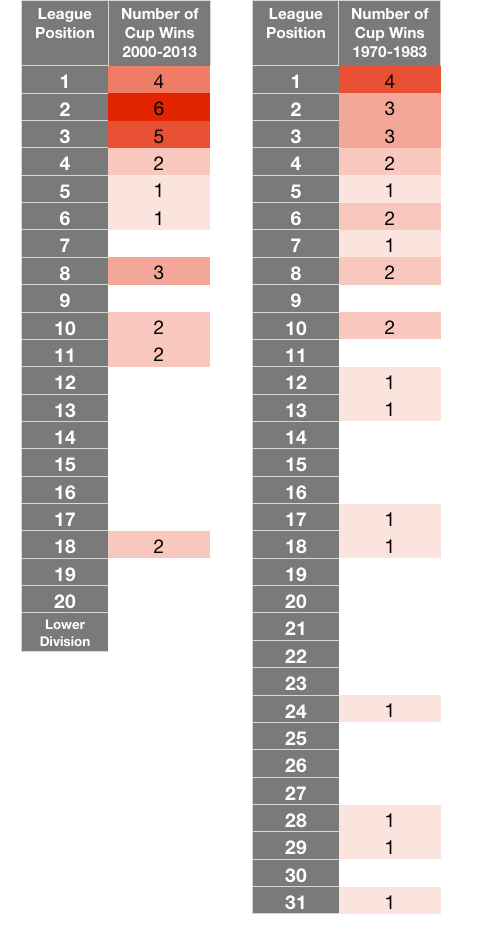

If you look at the heatmap below, you can see that the top three have won the vast majority of domestic cups in recent times: 15 between them since 2000.

Then it drops off, with 4th winning only two, 5th and 6th winning one apiece, 7th winning none, and a spike at 8th, with three. Is this spike due to those out of the running for the top four being able to concentrate on trophies, or is their focus on the trophies harming their league position? (It could of course be neither.)

Between 8th and 11th there are almost twice as many trophy winners than there are between 7th and 4th.

It’s almost as if the top three can relax and enjoy the cups, but the teams competing for 4th are putting all their energies into that end. Safely mid-table teams can also focus on the domestic cups, but those with a remote hint of relegation dare not take the risk. On the two occasions when they not only took the risk but won the cup, they were relegated.

It seems that, in the modern age, the team most likely to win a domestic cup will finish 2nd, perhaps because they are one of the best teams over a 10-month period, but find themselves in a position where can neither win the league (therefore turn to the cups) nor fall out of the Champions League places (therefore the cups present no risk).

The distribution of domestic cups between 1970 and 1983 seems far more natural. The number of wins descends steadily down from the best teams to the worst teams. There are no strange gaps, in the way that the new rewards seem to create in the modern table. The only blank area correlates to teams right towards the foot of the table, and that’s fairly natural, as they are the worst sides, who are having a bad 10 month period.

Serious

If every club takes a competition seriously, then it has value. If only half the clubs take it seriously, it is heavily devalued. These changes do not necessarily happen over night, but there’s an evolution, as priorities shift. The greater the rewards for being in the Premier League, the less the clubs from mid-table, down to the clubs mid-table in the Championship, care about the cups. It’s not just about money; it’s about prestige. They want to be playing Liverpool, United, City, Chelsea, Arsenal and Spurs, instead of Huddersfield, Doncaster, Yeovil, Barnsley and Burnley.

Take the FA Cup’s own evolution. First, Manchester United dropped out in 2000. Then weaker XIs started to be fielded by major sides. “Cup Final day”, which used to be live from nine a.m. on terrestrial TV at a time when there were just three channels, has over time shortened to just a few hours before the match. Then lesser teams started fielding shadow XIs. Next, the final itself started being played at five p.m., with Premier League games at lunchtime. Cup Final Day was no more, and the match itself almost seemed an afterthought.

It may seem sad, but it’s a fact of life. That’s how it has evolved. By all means campaign to celebrate the way things were, but clubs can only focus on what matters now.

Still, the FA Cup remains the domestic knockout trophy of preference for the top three; of the fifteen domestic cups won by the top three since 2000, ten (66.6%) have been the older, more revered competition. The League Cup remains won more often by a team outside of the top four than within it. The League Cup is won most frequently by a safely mid-to-upper-mid-table side (finishing 8th-11th).

Titles

It seems fair to say that traditionalists value league titles above all else. However, if you want to win the league, then you need to have been in the top four the season before. Barring a freakish outlier that has yet to appear, it remains essential.

It’s a stepping stone that cannot be skipped over. Winning the League Cup means nothing the season after. However, being in the top four can lead to a virtuous circle.

Getting into the top four doesn’t mean you will soon win the league, but you have to set up camp there first to stand a chance. In the Premier League’s entire 21-year history, no-one has ever won the title when finishing lower than 3rd the year before.

And 17 of the 21 titles have been won by the team who finished either winners or runners-up the season before.

In other words, 81% of the title winners since the old First Division was changed to the Premier League had a foothold in the top two, and of the four (19%) to have finished 3rd and then go on to win the title, two – Arsenal in 1998 and Man City in 2012 – had only missed out on 2nd by goal difference. So how can being in the top three be anything but essential?

The last team to finish outside of the top three the year before they won the title? Perhaps fittingly, Leeds United, the very last winners under the old system. No-one has done it since the changeover 21 years ago. And since the mid-’90s, when Newcastle finished 2nd, no-one who wasn’t in the top four the previous season has even managed to finish as runners-up.

Of course, people in the ‘70s and ‘80s moaned about Liverpool’s success, and the way they “always won the league”. Indeed, 13 times between 1970/71 and 1991/92 – the 21 seasons before the Premier League was created – a team from within the top three went on to win the title, with the Reds themselves retaining their crown on four separate occasions.

However, nine times – 43% of the time – the winners burst to the title from outside of the top three; compare that to the 0% of the past 21 years. Including Leeds and Arsenal, who both moved up from 4th to 1st in the final two years of the old system (1991 and 1992), the average prior finishing position for those nine teams was 9th. Aston Villa and Everton won the title in the ‘80s having finished 7th the season before. No-one has jumped from below 7th since 1978; no-one has jumped from below 3rd since 1992.

Derby County, in 1972, moved up from 9th to first, and Arsenal, in 1971, jumped from a lowly 12th to take the title. Most remarkably, Nottingham Forest finished “25th” – i.e. 3rd in the old second tier, behind 22 top-tier teams – before winning the title upon their first season back in the big time.

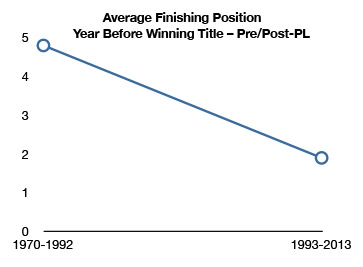

The graph below shows the finishing positions of teams the season before the they won the title.

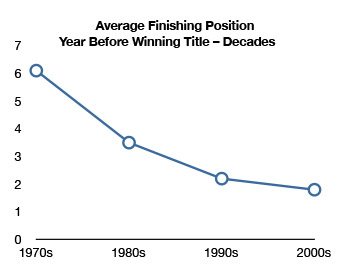

On average, a team with a finishing position of 6.1 would win the title in the 1970s – Liverpool dragging that number down, Forest dragging it back up – whereas between 2001-2010 it was a mere 1.8.

The following two graphs break down the average finishing positions, first comparing the 22 years before the Premier League was formed with the past 21 seasons; then, in the graph below, the decade-by-decade averages.

You can never say never, but it’s fairly certain that the next champions will come from United, Chelsea and City, because of the 21-year precedent. Therefore, if you want to win the league, you must surely prioritise getting into the top three, then strengthen for the next push.

They also happen to be in possession of the three über-squads in the Premier League; with TPI inflation taken into account, their 2012/13 squads were all worth over £320m each, whereas the two next-highest (Liverpool and Arsenal), were £185m and £174m respectively.

Liverpool may not have won the title since 1990, but the Reds’ two second-place finishes in the Premier League era (2002 and 2009) came when already in the Champions League. So, traditionalists who want the league trophy back at Anfield (and let’s face it, all Liverpool fans want that) need to accept that making it into the top three is the only way this is going to happen.

Also, cup competitions are easier if you are in the Champions League, because you can attract better players and afford stronger reserves. If you look at the non-Champions League teams that do well in the cups, it often seems to prove costly to their league form.

Swansea and Liverpool both went on poor runs after winning the League Cup, perhaps because of its position in the calendar, where players, having won something, relax in February. Birmingham were safe when they won the League Cup a few years ago, but went into free-fall and were relegated. Wigan had the best day of its history in the FA Cup, but were relegated days later. It may be coincidence, but they managed to survive seven seasons without a trophy, and as soon as they won one it came at the expense of their top flight status. Maybe their fans see that as a price worth paying? In many ways it is, although will it keep them warm on a Wednesday night in Huddersfield?

In the early years of the Premier League, Sheffield Wednesday, Arsenal and Middlesbrough all reached both domestic cup finals in a single season. Wednesday, who had previously finished 3rd in the final old First Division, dropped to 7th when reaching those finals. Arsenal, whom they played both times, dropped from 4th to 10th. And Boro, who had some wonderful players, ended up getting relegated, dropping from mid-table to 19th. It’s perhaps no coincidence that Liverpool, in reaching two finals in 2011/12, endured the worst second half of a season in living memory. The first half of the season was going well – the Reds were on course for 68 points – but the cup runs perhaps led to that total dropping to a poor 52.

Eschewing the smaller cups isn’t about disrespecting the club’s history, it’s about playing the ‘winners’ game in the current climate. While I can fully appreciate why some fans don’t like the way it is, you can’t pretend that the FA Cup is still as important as it was in 1965.

Crewe, Chesterfield and Carlisle have all won a trophy since Arsenal’s last success. But it was the Johnstone’s Paint Trophy, open only to the bottom 48 teams in the Football League tier. It’s all very well existing to win trophies, but they have to be the ones that are meaningful in your day and age. And as I’ve mentioned, Birmingham and Wigan, two more teams to win a trophy since Arsenal, suffered as a consequence.

In 1955, the FA didn’t even think the European Cup worthy of the time and energy, and Chelsea weren’t entered. In thirty years from now, perhaps the World Club Championship will be seen as more important than the Champions League, instead of an annoying distraction in December. (Although in South America, they already prize it very highly indeed, as their one chance to go head to head with Europe, where they know all their best players tend to end up. Look how crazy they go when they win, whereas European teams don’t need it.)

In the old days, Liverpool used to live to win trophies, and those main trophies would put the club into the European Cup (winning the league or winning the European Cup itself). For the last twenty years, non-champions have been able to get in by the back door, and whether it’s a good idea or not, those who can do so would be foolish not to walk through.

Once there, as shown in 2005 and 2007, it can define an era at your club. Istanbul was a miracle, we know, but the road to Athens, for example, was far more exciting and rewarding than any League Cup campaign. Being at the Nou Camp to see the Reds win 2-1 against Messi, Ronaldinho, Iniesta, Xavi, Deco and co., will live longer in my memory than beating Cardiff at Wembley or Birmingham in Cardiff.

The Liverpool team of 2008/09, which won nothing, was miles superior to the one that won the League Cup in 2003. In terms of the last 20 years, the 2008/09 was more like our Holland from 1978, and the 2003 team was closer to Greece in 2004.

The Premier League is the place to be, and the top four is the place to be within it. It’s almost like another division entirely, one up from the likes of Fulham, Norwich and West Ham, who, without the sudden arrival of billionaire owners, will almost certainly never gain access to the exclusive club.

Maybe that’s the way to look at it: the top four is the VIP area of the Premier League. You are all in the same venue, but you look on enviously at those behind the velvet ropes, to where the talent gravitates.

Relegation from the VIP area is very costly. Everyone talks about £40m games, £80m games, £120m games, but they do so for a reason. Football is no longer a relative meritocracy, as we outlined in Pay As You Play, but a sport where the imbalance of money leads to success for certain clubs. If Liverpool’s rivals have sugar daddy owners and Champions League income (and cachet), how do the Reds compete?

The top four is the place to be. But with the exception of investing a billion pounds, don’t ask me how to guarantee breaking into it. And while it’s not easy for a team to stay there after breaking in, it can lead to a virtuous circle.