Blackburn’s recent record had been abysmal. They had won just one of their last 17 away league games, and had failed to keep a clean sheet in 20 matches. Liverpool, however, are having trouble putting teams away; they are unbeaten in their last eight home matches, but have drawn four of them. And they have the worst shot conversion rate in the league this season, a miserly 8.6%.

First half

Blackburn moved away from their default 4-4-2/4-4-1-1, electing to start with a 4-1-2-3 instead. This was probably due to injuries to key defensive players, as the 4-1-2-3 offers more protection for the back four. N’Zonzi played the holding role, with Dunn and Gamst-Pederson just in front of him. Interestingly, Hoillet started on the left with Formica tucked in on the right.

Liverpool started with their usual 4-4-2, but with an untested combination up front. They played with inverted wingers, which usually means starting with double false nines. However, this time Dalglish opted for the less mobile but more directly attacking Carroll as the main striker. In theory this should have been the most attacking Liverpool team this season, with six attackers (the front four plus the two full backs as quasi-wingers) and a more traditional centre forward-creative forward partnership up top.

As I argued before the match, Liverpool needed to put as much pressure on Blackburn as possible, partly because of their injury problems and partly because of their general lack of defensive ability and tactical cohesion this season.

With Carroll freeing up Suarez to roam everywhere in the final third (wide or deep), and the full backs to provide overlapping runs and presence in the attacking zone, Liverpool certainly had an attacking line up. Yet they started the game rather slowly. They lacked intensity and attacking drive, the team looked static and disjointed in terms of movement and passing.

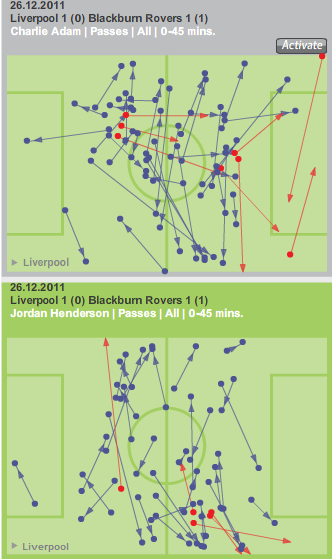

Blackburn’s midfield trio strangled the centre of the park and limited attacking opportunities for Adam and Henderson. Both Dunn and Gamst-Pederson tried to close them down as soon as possible, forcing them to knock the ball back to the defence or sideways to the flanks. N’Zonzi, playing behind these two, could either cover the gap left by a pressing midfielder or drop into the defensive line and offer additional protection to the defenders once Liverpool went down the wing. As a result, Liverpool lacked attacking penetration through the centre, with all of their attacking patterns pretty much one-dimensional and easy to anticipate for Blackburn’s defensive players.

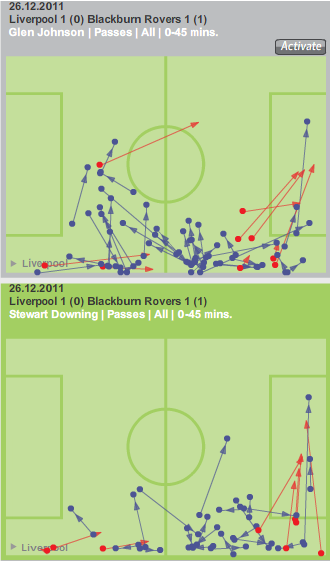

With the centre flooded, Liverpool were forced to play in wide areas. They favoured the right where both Downing and Johnson could target Blackburn’s inexperienced left back (the 17-year-old Henley). As a result, Liverpool stretched the play on the right with Johnson and Downing taking turns over who would run at the defender and who would tuck inside slightly as the passing outlet. Theoretically, this should have liberated the players on the left flank to roam inside and get closer to the front two. That would overload the defence by allowing the attackers to play quick passes with each other and by getting more bodies into the final third. In practice it never happened due to poor ball distribution and poor timing of runs, off the ball movement and generally poor team cohesion.

The rest of this post is for subscribers only

[ttt-subscribe-article]