So, according to Derek Llambias, the Newcastle managing director, Andy Carroll is worth ‘fuck all’. Of course, having bragged of turning down a bid of £30m, at which point Liverpool could easily have walked away, they must have had some sense of his value, but that’s by the by. Either way, at £35m, Andy Carroll remains a news story. Welcome to the goldfish bowl.

The price tag won’t go away, and perhaps that’s the Geordie’s biggest handicap. People expect a lot, and expect it immediately.

Recently I’ve been trying to think back about notable target-men – their goalscoring records and their ability to bully defences – and how long it took them to develop their game. The evidence (which I will come to) suggests that, actually, Carroll – at just 22 – is very well developed in relation to other players of his ilk. That doesn’t mean he’ll go on to prove a smash-hit sensation – potential of all shapes and sizes has sped down the drain – but people often make the mistake of not taking the type of player into account when looking at age.

I’ve always felt that smaller, quicker strikers peak young, and slower, bigger strikers peak later. This is a general rule, and there will of course be exceptions. As a rough guide, I feel that it has a lot of merits.

Pace can get forwards into goalscoring chances, so an average 17-year-old with jet-heels can beat even the best defenders now and then; but without pace, a striker needs to rely on movement, cunning, positioning; and as with the arts of the centre-back, these are skills honed with time and experience. Centre-backs peak after their mid-20s, and I believe the target-man does, too.

When previously considering this, I tended to think of slower strikers as the type who dropped deeper and looked for openings; the clever no.10, who played the passes for the nippy no.9 to run onto. But what about the ‘old-fashioned’ no.9? (Which, in itself, is a term that does players like Carroll no favours; a nod to the old days of English football when, it seems, every forward was a giant.)

As hard as I’ve tried, I’m yet to discover any target-men who were at their best – or at least, already highly prolific – in their teens; I can’t find the target-man ‘major league’ equivalents of Michael Owen, Robbie Fowler, Nicolas Anelka, Fernando Torres, Lionel Messi, Kun Aguero and Wayne Rooney, who were probably capable of 20 goals a season in the strongest divisions by the age of 18. Maybe they exist, and I’ve just overlooked them, but they don’t leap as readily to mind.

But more on that a little later.

Target Style

Andy Carroll isn’t as slow as people make out, but he doesn’t have that extra change of pace to get away from defenders, and obviously, when up against sprinters for centre-backs, he can look laboured. He has good technical ability, in terms of lay-offs and hold-up play, and has a sweetness in his left-foot that many strikers of any size would envy. However, although it can be coached, his movement off the ball isn’t yet that great.

His status as a ‘traditional’ no.9 is based on his size and aerial ability, although at Liverpool his heading has been fairly wayward; to me, evidence of a lack of confidence, given the way he frequently rose to meet crosses with towering headers at Newcastle. Again, this sense of unease with his own game is down to developing gradually within a familiar environment, with low expectations, then dramatically yanked out of his comfort zone and suddenly expected to play like a ‘£35m player’. It takes time to develop, and it often takes time to adjust to a new club.

I actually think that Carroll is starting to come of age for the Reds away from home; it gives him the chance to hold the ball up for Suarez and the midfield support, and it also means that he’s not facing the kind of packed defences he encounters at Anfield, where it’s more likely he’ll be crowded out. His understanding with Luis Suarez has blossomed in away games in particular, and overall – and somewhat counterintuitively – Carroll has played just behind his strike partner in most of their games together.

With five goals in 21 matches for the Reds (albeit just 14 starts), he’s doing okay. This season, all three of his goals have come on the road, and none has been headed. Part of the problem has been his team-mates too frequently hitting long balls in his direction, to the point where Liverpool have probably played its best football in his absence; however, there have been plenty of games where the ball was kept on the deck with the big no.9 in the side, and also some poor performances when he’s been absent.

Although the Kop support him, I sense that he hasn’t had quite the goodwill afforded to Peter Crouch, even though it took the gangly £7m striker 19 games to finally find the net for the then-reigning European champions.

Had Carroll cost £7m, he’d be viewed more favourably on his performances thus far. Fees clearly affect perceptions (as well as the player’s own game). But if everyone can just get past the price tag, and view him as a component of the team, rather than a costly individual, he might stand a chance.

You can always argue that such a fee could have been better spent, but with Suarez, Enrique and Bellamy all bargains, you can’t win ‘em all; some signings will seem cheap at twice the price, others expensive – it’s the way it goes. The key is now coaxing the best out of the big no.9, rather than obsessing with what he’s not (i.e. Kun Aguero. Or, indeed, Luis Suarez…).

Most importantly, given Carroll’s age, and the type of player he is, if comparisons are to be made, they need to be like with like. Observers need to appreciate the longer learning curve of the target-man.

Perhaps this type of player is rarely viewed as world-class – unless they have pace, they find it hard to be consistently devastating – but many have proven increasingly prolific (even pretty mediocre versions, like Kevin Davies), on top of the focal point/spearhead qualities they bring.

Compare and Contrast

No two players are identical; therefore comparisons can always be criticised. In thinking of a whole host of target-men over the past 20 years or so (mostly in England, but also further afield), I realised that some were quicker than others, and that there was a wide range of heights, even though I set the minimum at 6ft; the maximum topped 6’8”.

I wanted to do my best to avoid comparing apples with oranges; all the while accepting that, given differences within the different striking genres, I may have to compare apples with pears, and oranges with clementines. Once I’d worked out how the traditional no.9s performed I could then look at the differences in trends between target-men and the generally smaller, more mobile variety of forward: only then comparing the apple and the orange.

I looked only at performance in the top divisions main five European leagues (England, Spain, France, Germany and Italy), and only compared goalscoring records in league games; to exclude games against substandard opposition, either in weaker leagues or in cup ties where strikers can fill their boots. (Target-men obviously do much more than score goals, but it’s the most obvious comparison that gets made; and assist and chance creation data goes back only so far.)

Given the nature of this site, I tried to include as many Liverpool players as possible, but the list mostly comprises non-LFC players. Obviously the players I looked at have been in teams of varying quality; some good, some bad, some great, some woeful, and so on. So again, it makes comparisons difficult, but I’ll try all the same.

Exceptionally quick and/or skilful tall strikers like Zlatan Ibrahimovich and Thierry Henry were excluded, as they could just as easily fit into the ‘oranges’ category I wanted to later compare against. I also excluded target-men who’d started as wingers (such as Emile Heskey), as it’s harder to say when they became a target-man.

In total I looked at 23 ‘target-men’, and 11 strikers who relied more on a combination of pace, skill and finishing than aerial challenges and hold-up play. All names (beyond those with an LFC connection) were chosen randomly and without bias – the ones that sprung to mind, and the suggestions other people made to me.

(Some further names – and good ones at that – were mentioned to me after I’d crunched the data, but maybe I can go back and expand it at a later date. I’ll mention some of those names at the end of this piece, but they are not included in the overall averages.)

Overall, the target-men in the mini-study average 97 top-league, top division goals apiece, at 8.8 per season. The mobile goalscorers average 130 goals each, at 10.7 per season.

All About Age

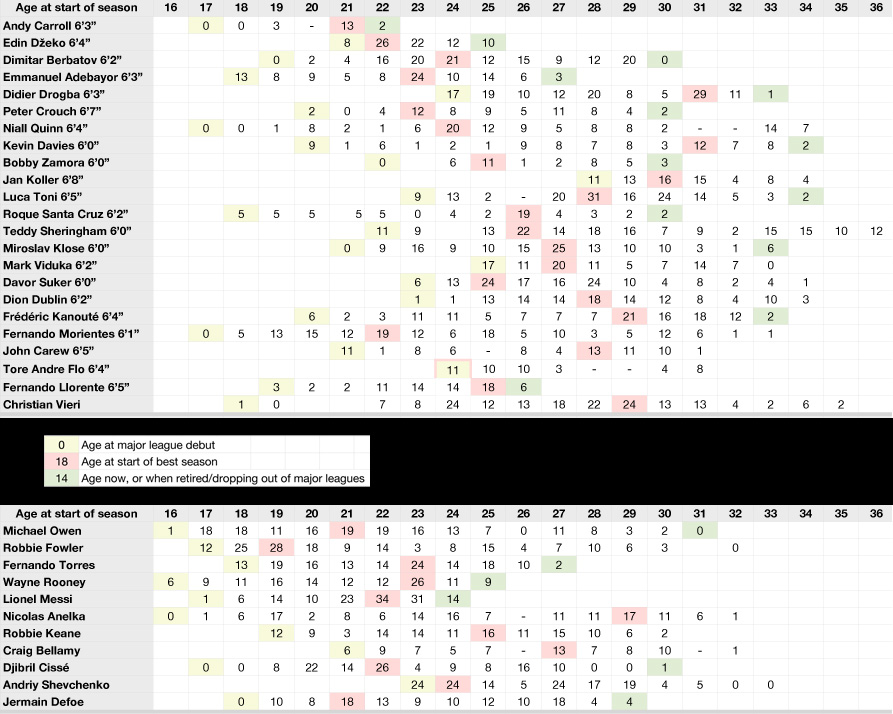

Only three of the 23 target-men I studied made their league debut as early as 17, and Carroll was one of them. Three more made their debut at 18, but the overall average for playing their first game in a major league top division worked out at 21. Clearly, as suspected, target-man is not a young man’s game; by contrast, the average of the 11 smaller/quicker strikers is just 18, with three of that category making their first league appearance at just 16.

(In calculating age, I worked out how old the players were at the start of each season.)

Out of the 23, only two had managed double-figures in a qualifying league before the age of 20; with 13 the highest amount registered. However, eight of the 11 smaller/quicker strikers had reached double-figures at the age of 19, four of whom exceeded 17 league goals in a season.

In total, 15 of the 23 ‘apples’ had their best season (or best season to date) aged 25 or over, whereas six of the 11 ‘oranges’ had their best season aged 23 or younger (only two of the 11 peaked after 25). Above all else in the study, this, to me, is the most revealing stat. Whatever the relative merits of the different kinds of players, that seems highly pertinent.

Of course, Carroll, at just 22, is still some way off his mid-20s, and Edin Dzeko is 25 right now; therefore neither are applicable here when it comes to peaking after 25. So in essence it’s 15 out of 21 who peaked aged 25 or over. In other words, three out of every four target-men will have his best season in his mid-20s or later. (Going back further, I just checked John Toshack’s stats: slow start after joining Liverpool aged 21, and his best season aged 26, in 1976.)

Excluding Carroll and Dzeko, two of the three remaining strikers to have experienced their best season when under 25 – Emmanuel Adebayor and Peter Crouch (both 23 at the time) – are still playing, and quite conceivably yet to have their best season (though this seems less likely with Crouch, now that he’s 30 and not at a big club).

Eight of the 21 had their best season aged 28 or over, and three of those had their best-ever season in their 30s. Only Fernando Morientes peaked young, with his best season aged 22, although he had some highly effective seasons up until the point he joined Liverpool in his late 20s. For Andy Carroll to have managed 13 league goals in a single season at the age of 21, having moved clubs halfway through – and moving clubs has hampered many on the list for a year or two – and missed a large chunk of the campaign, is highly impressive; look below at how few other target-men were posting similar figures in a tough division by that age.

(Click to view full size. Where players have two or more best seasons, the one with the fewest games played is counted.)

(Click to view full size. Where players have two or more best seasons, the one with the fewest games played is counted.)

The overall average age for best season for target-men is 26.4, with it standing at 25.7 for players still active in the relevant leagues, and 26.5 for those who have either retired or moved to less-competitive environs. Compare this with the average age of 23.4 for the peaking of the 11 non-target-man strikers, and again, it suggests that although they may not burn as bright to start with, they come into their own later in their careers.

None of this means that Carroll will develop into the kind of striker he has the potential to become; the no.9 Rio Ferdinand felt could be ‘unplayable’. But it does go to show that even though he’s not the finished article, he’s arguably ahead of many of the great names we now look back on as masters of the art at the same stage of their careers.

(Target-men not included: Gabriel Batistuta, major league debut at 22, best season aged 25; Les Ferdinand, major league debut at 20, best season 25. Smaller strikers overlooked: Ian Wright, debut 22, best season 29; Kevin Phillips, debut 27, best season 27; Kun Aguero, debut 18, best season 22. Alessandro Del Piero, Serie A debut 19, best season 23.)

Further analysis of the target-men in the study follows, for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]