Some people in football get tarred with a dirty big brush early on, and struggle to rid themselves of the coal-black stain.

I have a sneaking suspicion that, for some Liverpool fans (as well as those outsiders who like to criticise), Damien Comolli could be the next Rafa Benítez: foreign, studious and mocked. Above all else, misunderstood.

There’s some tetchiness creeping into the fanbase, albeit possibly just the usual knee-jerk suspects who cry foul each and every season. I’ve received messages from supporters criticising almost everyone: Comolli (“he has to be sacked!”), FSG (“they don’t know what they’re doing!”) and even Dalglish (“stuck in the past!”). Football365 published a mailbox that appeared to damn everyone involved with player recruitment at the club.

Most of this has been based on the summer’s transfer activity – including players merely linked with moves in and out via speculation – and ignores the fact that Liverpool made massive strides last season when FSG, Comolli and Dalglish were in tandem. Inheriting a side languishing in 12th, Dalglish’s Liverpool finished 6th; but it would have been 3rd based purely on results following Hodgson’s departure. (A few people got a bit uppity when the Reds lost the final two games, but by then, to quote Dalglish, the club simply ran out of fit senior players.)

Comolli and Dalglish have very different skill sets. Between them, they can cover a lot of bases. By all accounts, following extensive scouting by himself and his team, Comolli creates a shortlist for Dalglish to choose from, rather than forcing signings onto the manager. The Frenchman knows that the manager has to be happy with who he receives, and his job is to narrow down the field.

There’s also been a small backlash that, due to appointing Dalglish, Chelsea were free to pursue Andre Villas Boas, with some suggestion that appointing ‘King Kenny’ was harking back to the past. (A view I might have shared a few years back, but which was clearly wrong.)

I’ve little doubt that Villas Boas would have been ideal for FSG and what they are trying to achieve. However, it ignores that Chelsea are in the Champions League, not to mention his previous strong connections with the West London club (so it’s not like he would have certainly turned them down in favour of Liverpool – just as procuring elite players this summer will be nigh-on impossible given the incredible emphasis that almost all of them place on the Champions League).

Also, it has to be noted that FSG were delighted with the way Dalglish performed, and that no manager alive would have had as much chance of uniting the club at what was clearly a time of crisis on the pitch. Based on results and, just as importantly, how he handled both himself and his players, he merited the job. If Villas Boas fits the FSG model, Dalglish fits Liverpool FC. At a time when harmony was restored, both on and off the pitch, to have jettisoned Dalglish would have been crazy.

The Fall Guy

Perhaps Comolli is the easiest to blame when fans start to see things they don’t agree with. He’s young, French, never played professional football, and occupies a position that is greatly mistrusted in the English game. Directors of Football, and others who work primarily behind the scenes, are easy to write off, and dismiss as offering nothing; you can’t see what they do, so it doesn’t exist.

At Spurs, Comolli was widely derided, and yet if you look at his player recruitment record, it’s actually very impressive. Not every player worked out at the time, but many have since come good, both at Spurs and elsewhere. (See our analysis on the TPI site.)

The Daily Mail’s Martin Samuel has today written a bizarre piece about Comolli. It’s interesting that he puts all the ‘blame’ for the club’s English buys at the Frenchman’s door, when Liverpool have already explained that recruitment is a groupthink strategy. (Others, who think Dalglish is a dinosaur, are putting the blame solely at his door.)

Had Roy Hodgson been buying these players, you suspect that Samuel would have been telling us how right the manager was for Liverpool. But maybe I’m a hypocrite: had Hodgson been buying them I’d be far more worried, but mostly because everything he touched turned to tripe, including the way the Reds played.

Choosing to focus on some strange angles, Samuel spends two paragraphs talking about a young Spurs keeper who cost £1m, and has played only one first team game. So what? Even the best reserve keepers can fail to get a look-in. Even though Samuel accepts that it was low-risk, criticism is still implied. (And of course, if Comolli was buying too many foreigners, you can imagine the outcry.)

Here’s more from Samuel:

Sound familiar? It was a policy Comolli inherited and then pursued at Tottenham with conflicting results. The club had already established its penchant for the bright British prospect when Comolli joined in September 2005, following the acquisition of players such as Calum Davenport, Sean Davis, Michael Dawson, Michael Carrick, Jermaine Jenas, Jermain Defoe and Andy Reid by the previous regime.

At the very least, Comolli maintained this project and arguably accelerated it with buys including Darren Bent, Gareth Bale, David Bentley, Jonathan Woodgate, Ben Alnwick, Danny Rose, Alan Hutton and Chris Gunter.

He bought from abroad, too, but Tottenham were largely known for taking a punt on a domestic prospect. The difference being it was not such an inflated market then.

Having looked at transfer prices and inflation in Pay As You Play, that last point is bogus: since the time Comolli was at Spurs the average price of a transfer has risen considerably. (See Dan Kennett’s piece on why English talent has been overpriced for years, and in current terms, may actually be cheaper right now; £48.8m on Shaun Wright-Phillips to Chelsea and £41m for Michael Carrick’s move to United in 2011 money?)

This doesn’t alter the fact that Comolli made several game-changing transfers at Spurs, and just as Alex Ferguson buys flops like Tosic and Bebe, it’s the signings like Rooney and Hernandez who win him trophies.

“He bought Bale for £10m and the player could one day be sold for five times that; except Bale’s career was going nowhere until rescued by Harry Redknapp and this time last year the jury would have been very much out on his worth.”

Is it Comolli’s fault that Bale took a couple of years as a very young man to realise his potential? And why didn’t Redknapp rescue his career before last year, having taken over as far back as 2008? Why the need from the writer to include that meaningless caveat? Comolli’s job was to find untapped talent. If you buy a 17-year-old, then unless you are particularly stupid, you accept that he might not be an overnight sensation.

(More on Comolli at Spurs: Berbatov, as he was then, Bale and Modric would get into most sides in the world, even if the Welshman is a little overhyped at times. Darren Bent failed under Harry Redknapp, but has succeeded at Sunderland and Aston Villa. Kevin-Prince Boateng had an excellent season on loan at AC Milan last year, and this summer they took up their option to buy him. And Adel Taarabt, now at QPR, has immense natural talent. In many cases it was just the timing that was out: Bale, Boateng and Taarabt were simply too young and/or new to English football to immediately prove themselves; as was Modric, who was mocked after a slow start. And while never going to be ‘world class’, Darren Bent continues to outscore the players Redknapp bought to replace him, and to be sold for high transfer fees. Roman Pavlyuchenko has done fairly well, without ever being exceptional; but a damn sight better than Robbie Keane since his ill-fated return to the club in 2009. Assou-Ekotto and Alan Hutton have also done pretty well. However, Comolli’s major mistake was appointing Juande Ramos as manager.)

Samuel also misses a key point: namely that Liverpool have to buy English, and preferably young. Why?

Catch Up First, Moneyball Later

One of the most commonly overlooked concepts of the Moneyball principle is that you overpay to plug gaps. Perhaps the best example of someone failing to do this is Arsene Wenger at Arsenal. Having built an exciting, vibrant team that looked capable of challenging for the title last season, the good work appeared to be undermined by the lack of an experienced, established goalkeeper. Such a clever exponent of finding cheap young talent (once with Comolli’s assistance), Wenger did not appear to do enough to adequately fill arguably the most important position in any side. Even if Arsenal had to pay £10m over the market price, it’s possible that the rewards would have been far greater.

By January 2011, Liverpool had a number of holes in the squad, the most notable being up front. After his failed dalliance with Robbie Keane in 2008/09 (thanks again to Redknapp for taking him back for up to £15m), Rafa Benítez had wanted to reinvest the recouped fee on Stevan Jovetić, the accomplished young Fiorentina striker. According to Benítez, he was told he could spend the money recouped on player sales, plus £20m; only for the extra money to be withdrawn later in the summer, after Glen Johnson and Alberto Aquilani were purchased. As players continued to be sold and the money used to service the debt under Gillett and Hicks, then so the squad thinned out. FSG inherited that problem.

It left a hole up front that was not filled by Roy Hodgson, whose purchases were mainly aging midfielders and aging left-backs; a hole which threatened to widen into a chasm with the exit of Fernando Torres. And while Luis Suarez was an exciting signing, he was not seen as adept at being the spearhead striker, and had he been the only replacement for the Spaniard, the hole would merely remain the same size. Liverpool needed to make a statement.

So, despite being prepared to pay over the odds (because they were selling Torres for such a high fee), Liverpool required a proper centre-forward and Andy Carroll was that man. And yet Carroll also helped fill another gap: he was young and English, at a time when the club lacked in that area.

When Benítez overhauled the Academy in 2009, one of the reasons was the lack of English youth internationals at the club; sufficient quality was not being found, and it was driving the manager mad. (In my 4-hour interview with him in 2009, this was his most passionate topic.) Finally, two years ago, he got his chance to revamp the failing youth project.

His appointments – Barcelona duo Pep Segura and Redolfo Borrell, Liverpudlian Frank McParland and legend Kenny Dalglish – helped change that, to the point where the club currently has no fewer than six kids in the England U17 party at the youth World Cup, and a few weeks ago, five starlets starting for England U19s (and it may have been six had definite starter Jonjo Shelvey not been injured); all as part of 25 youth internationals now on the books. (Segura recently said that there were just two back in the summer of 2009.)

However, despite this brilliant teenage potential aged 19 and under, how many England U21 players did the club possess back in January of this year? By my reckoning, just Martin Kelly (with Jay Spearing yet to be called up, and not making this summer’s tournament squad, and is now too old). The additions of Andy Carroll and Jordan Henderson make it three, and interest in Phil Jones and Connor Wickham shows an intent to increase that.

As I noted here, Henderson and Carroll may have inflated fees but will surely be on far more reasonable wages than some of the recent ‘free’ transfers.

A big part of FSG’s strategy is to lower the wage bill, and to not overcommit on long, expensive contracts to the likes of injury-prone Sylvain Marveaux, who chose Newcastle because they offered a longer, more lucrative deal which was too risky for LFC. Roma’s keeper Doni didn’t want to take a 60% pay cut and sit on the Anfield bench watching Pepe Reina. Brad Friedel, aged 40, simply didn’t want to sit on the bench, whatever the money, in the twilight of his career. All three are non-Brits, but they turned Liverpool down for their own reasons. None were high-priority targets, though, and with that in mind, Liverpool did not go the extra mile to land them. That may be different with the left-back targets of Clichy and Enrique, but as both are 12 months away from being free agents, it may be a case of deciding how much of a deduction in price is appropriate.

But like it or not, Liverpool need to have a certain number of English players in the match squad, and with further quota plans mooted, it may need to be as many as six in the starting XI.

Back in January, aside from Kelly, only Glen Johnson was young enough and good enough to feel confident about lasting the next few years, so work needed doing, until what could possibly be a golden generation filters through. Hodgson’s English solutions – Cole and Konchesky – were disastrous, and along with Gerrard and Carragher, did not have age on their side.

Do I expect Liverpool to keep ‘overpaying’ for English talent? No. In time, Comolli and FSG can afford to be more patient in their recruitment – which is not to say that they are panicking or buying in haste now, just that the situation should smooth itself out in the coming seasons.

However, when the Reds are meeting the asking prices, they are being criticised for overpaying; when they refuse to meet wage demands and/or big fees, they are slated for lacking ambition or moving too slowly.

Comolli’s Way

If there’s one thing I’m sure of, it’s that FSG know what they’re doing. Or rather, they have clear ideas on strategy and how to run sporting institutions, even if football is new to them, and what they attempt might not work – although so far, if the proof is in results, they’re clearly succeeding.

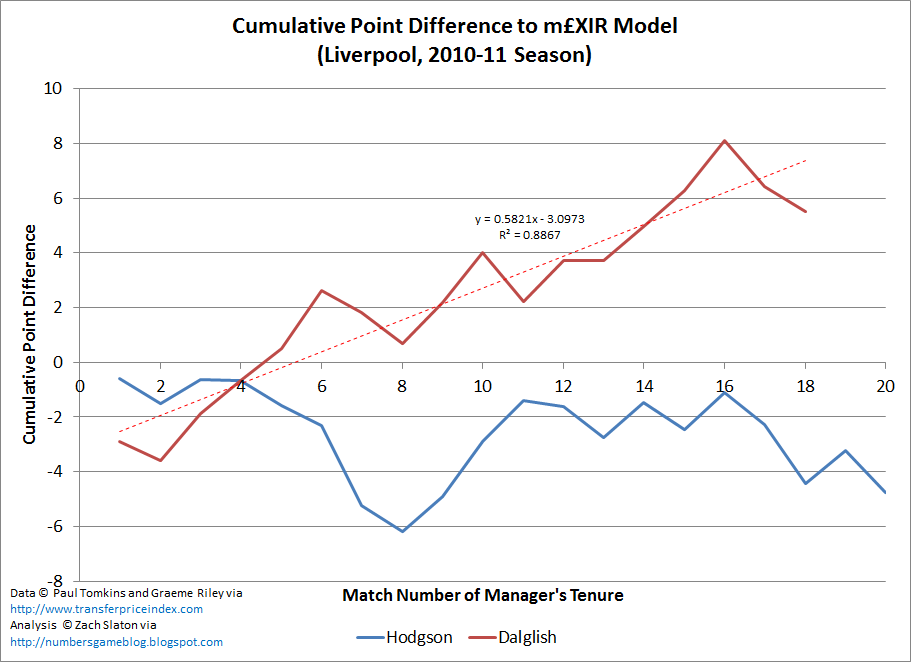

The second half of this article by Zach Slaton outlines how Liverpool improved after FSG’s first major decision last season. While it may not make sense out of the context of the piece (which is fairly complex, so be warned), the graphic below plots Liverpool’s results last season under Hodgson and Dalglish, in relation to their odds of winning matches (based on the cost of the XIs, with inflation taken into account).

FSG’s whole modus operandi is built on the power of information, not simply winging it.

As such, Damien Comolli is one of the key figures in Simon’s Kuper’s outstanding piece on the new data revolution in football.

Comolli’s three years at Spurs encapsulated many of the early struggles of the data revolution. British football had always been suspicious of educated people. The typical football manager was an ex-player who had left school at 16 and ruled his club like an autocrat. He relied on “gut”, not numbers. He wasn’t about to obey a spreadsheet-wielding Frenchman who had never played professionally himself. Comolli was always having to fight “nerds versus jocks” battles. With hindsight, he unearthed some excellent players for Spurs: Luka Modric, Dimitar Berbatov, Heurelho Gomes and the 17-year-old Gareth Bale. Yet eventually Comolli was forced out.

. . .

From his perch at Anfield, Comolli often chats to the father of Moneyball 5,000 miles away. Beane says: “You can call him anytime. I’ll e-mail him and it will be two in the morning there and he’ll be up, and he’ll e-mail me and say, ‘Hey, I’m watching the A’s game’, because he watches on the computer. The guy never sleeps.” At Liverpool, Comolli has genuine power. He has said that data informed the club’s recent purchases of Andy Carroll and Luis Suarez for a combined £60m.

The same level of research applies to Jordan Henderson, who has suddenly become a bit of a joke figure, in the way that the Brits love to knock their own. Last October, Steve Bruce was talking up Henderson, using statistics: “He’s a fantastic footballer. Jordan’s got the lot. He’s 6ft 2in but he covered 13 kilometres against Aston Villa without giving the ball away. He can tackle, he can pass, he can cross, he just needs to score a goal but he can do that, he can hit the ball. How many 20 year-olds are playing week in week out in the Premier League?”

Henderson went on to be one of the league’s top chance creators, and Comolli will have assessed how he went about doing that. Nothing guarantees that he will do the same under greater scrutiny at Liverpool, but if he’s given time to settle, he can grow as a player and pick out passes for the likes of Gerrard, Suarez, Carroll and Kuyt. The way Dalglish handled Flanagan and Robinson last season – putting them at ease, removing the pressure – suggests that Henderson could blossom under Liverpool’s greatest living patriarch (as opposed to the way playing for England could simply be throwing him to the wolves.)

Stewart Downing is another accomplished chance creator. He’s not a ‘glamourous’ winger, but he is a versatile team player who delivers for others, and who can score himself. Most of us would prefer Mata or Hazard, but thanks to Gillett and Hicks, whose decisions turned a top-four team into one fighting relegation just eight months ago, Liverpool are a slightly harder sell right now. The likes of Downing and Charlie Adam would undoubtedly improve the squad, and it just needs the Reds to scrape 4th place to look a far more exciting proposition in 12 months’ time.

Comolli will continue to make mistakes, just as anyone in football does. My theory is that only 50% of transfers work out, for a variety of reasons, and maybe only 20% are what I call game-changers. But he learned a lot of lessons from his time with Spurs, and he’s determined to reduce the odds for making errors. With his intelligence and Dalglish’s experience, Liverpool could have a winning back-room team, providing they work in unison (and so far, there’s nothing to suggest otherwise).

Philosophies

In this excellent interview with Leaders in Performance, Comolli outlines some of his philosophies.

The process of recruitment is, more than ever, a strategic operation. At a first team level, due diligence must be afforded to potential multi-million pound acquisitions. The initial player recommendations of the scout are followed up by at least 3 to 4 more viewings from ‘other’ senior staff. Subsequently, three positive reports will trigger a ‘buying’ mechanism, ‘the beauty of having different people is that different people watch different things. They have a slightly different eye, depending on their experience, their personality or background as maybe a coach or maybe a player… the diversity is key… you want to develop a situation where people can challenge, challenge me or the manager. You know, saying that’s my opinion, you may not agree with me but I’ll give you my opinion because that’s the way I think and that’s what I’ve seen… you want your scouts to be strong, not sit on the fence, make a recommendation, yes, no, why. You want a strong recommendation either way.’

Anyone panicking should read that. And this:

As for the future of talent recruitment, Comolli extends his need to understand every detail of a player before the club decide to sign them. The need for (accurate and reliable) data and information; physiological, physical, technical, psychological and social is critical to help inform decisions. As is the case in America, he believes that psychological profiling prior to signing a contract will emerge in England and in Europe. The sense of knowing the person as opposed just the player appears critical. At the earlier age Comolli would like to be able to predict the work load capacity of a player before signing them. In essence, he wants to know if they can cope physically with the demands of top-level football. Something similar occurs in US baseball with the physical assessment and work load capacity of the pitcher’s arm. Comolli’s not quite sure whether this will transfer or translate to football just yet, but I’m sure he’ll find out pretty soon.

It might take time, but the more we try to understand what’s going on at the club the better our chances of judging transfer activity. Of the other big clubs, only Manchester United have signed anyone of note, but they are also one of the only big clubs to lose key players this summer (Van der Sar, Scholes).

A little patience is required. Last season, Steven Gerrard barely played under Dalglish, and never started alongside Andy Carroll. These two alone could feel like big summer signings if they are fit and raring to go come August.