By Joseph Pepper (long-time TTT subscriber).

Note from PT: this is TTT’s longest-ever piece, but it’s well worth going to the trouble to read. Print it out and voilà! – you have (almost) a book. (Hell, Joe has already split it into chapters for you.)

Part 1. Pascal’s Triangle.

“In practical life we are compelled to follow what is most probable; in speculative thought we are compelled to follow truth.” ― Baruch Spinoza, The Letters

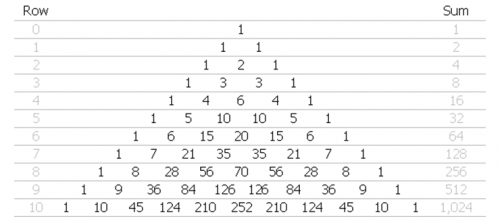

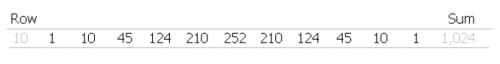

The above image is of Pascal’s triangle, named after French mathematician Blaise Pascal. It is a triangular array of the binomial coefficients. More importantly, it also explains how Liverpool’s 2013-14 Premier League season became the most extraordinary league campaign of the modern era.

The first row of Pascal’s triangle is just the solitary number 1, and the second row is two 1s offset to either side. Each row after that contains one number more than the previous row and begins and ends with a 1. All numbers in between are the sum of the two offset numbers above it.

One useful function of Pascal’s triangle is that it tells you the probability of getting a certain number of heads or tails from a given number of coin tosses. Counting from zero and going down, the row number tells you the number of coin tosses. The far right column, “sum”, is the sum of all the numbers in that row, and tells you the number of unique possible outcomes from those coin tosses. For example two coin tosses (row 2) has four possible outcomes (heads-heads, tails-tails, tails-heads, heads-tails) ). The number of unique possible outcomes is also equal to 2-to-the-power-of the row number. For example 2 to the power 3(row 3) is 2x2x2 = 8.

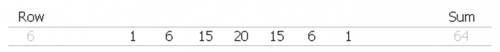

To see the probability of getting n number of heads from a given number of coin flips (the row number), take the nth number in that row, and divide it by the sum total in the far right hand column of that row. For example, say you wanted to know the probability of getting three heads from six coin tosses. Go to row number 6 (the 7th row down, remember it counts from zero).

Look at the 3rd number in that row, again counting from zero, (20) – then divide it by the sum on the right hand side of that row – (64). This gives you 20/64. Or 31.25%. So when tossing a coin six times, the probability of getting exactly three heads (and three tails) is 31.25%.

At this point, intuition may be telling you that the probability of getting an equal number of heads and tails should be 50/50, not 31%. Each coin toss is as good as 50/50 and each coin toss has no bearing on the next one, so why is the probability of getting an even heads/tails split not 50-50? The answer is that whilst it’s true that each coin toss does not influence the next in any way, an even split of heads and tails is just one of many combinations that could result from a given number of coin flips.

If we look at ten coin tosses instead of six, we can see that the probability of an exactly even split is even lower. This is because there are even more unique possible outcomes from higher numbers of coin flips. In the case of ten coin flips, go to number 10 (11th one down), look for the the 5th number (again counting from zero) – 252, and divide it by the sum on the far right of that row – 1024.

This comes to about 24.6%. Compared with our chances of an exact 50-50 split from six coin tosses (31.25%), it shows that the probability went down, relatively speaking, by almost a quarter. It is exactly analogous to being less likely to have a winning a lottery ticket (one unique outcome), the more people have entered the lottery (more unique possible outcomes).

This comes to about 24.6%. Compared with our chances of an exact 50-50 split from six coin tosses (31.25%), it shows that the probability went down, relatively speaking, by almost a quarter. It is exactly analogous to being less likely to have a winning a lottery ticket (one unique outcome), the more people have entered the lottery (more unique possible outcomes).

But what if, instead of looking at the probability of an exactly 50-50 split, we look at the probability of getting all heads with a given number of coin flips? In our two above examples (six coin tosses, and ten coin tosses), counting down and across again, we see that the probability of getting all heads are 1/64 (1.6%) and 1/1024 (0.097%) respectively. In relative terms, this means the probability for getting all heads went down by roughly a factor of 16(!) as we went from six coin tosses to ten. This is compared with a probability reduction of only about a quarter for the even heads/tails split. Since we already observed that all the numbers in the far right hand column equal 2 to the power of the row number, and since we can see that all of the numbers along the edges of the triangle are 1s, this tells us that the probability of getting all heads (or all tails) reduces exponentially with every added coin toss.

In summary (and really this is the important bit), what this means is that the more times you flip a coin, the less likely it is that you will get all heads (or all tails). By extension, the more times you flip a coin, the less likely you are to deviate from a 50-50 distribution of heads and tails, since (relatively speaking), the odds of getting mostly heads, or mostly tails, is reducing exponentially with each consecutive coin toss. You can easily test this if you have the patience. Flip a coin four times, and record the relative distribution of heads and tails. Then do it eight times and do the same. Then repeat for 16 coin flips, 32 coin flips, 64, 128 and so on. The overall pattern you will see is that for higher numbers of coin flips, the relative distribution of heads and tails will converge closer and closer to 50-50. If you don’t see this, then something highly statistically improbable has happened. Do it again!

The coin doesn’t have a mind of its own. It doesn’t care whether it lands heads or tails. Each coin flip is completely independent of the one that preceded it and is not affected by it in any way. A coin toss can be thought of as a statistically independent, discrete probability event. But when multiple coin tosses are taken as a whole rather than in isolation, there is a clear convergence. A regression to the mean. Randomness is reduced as a factor in higher numbers of flips. The more discrete events with a certain probability there are in a given scenario, the more accurate the representation of the underlying probability will be.

Incidentally, this does not mean that if you get heads on one flip, you are more likely to get tails on the next. This is otherwise known as the “Gambler’s fallacy”.

Part 2. What The Hell Is He Doing?

On the 12th of January 2014 Liverpool defeated Stoke City at the Britannia Stadium. At the time of kick off, Stoke had conceded seven goals in ten matches and Liverpool had not won a league game at the Britannia in the Premier League era. With 66 minutes on the clock, Liverpool were leading 3-2 having managed to reclaim the lead following a disastrous first half surrendering of a two goal cushion. At this point Brendan Rodgers decided to bring on striker Daniel Sturridge. Rather than protecting a lead that had already been so catastrophically lost barely a half hour earlier, the Liverpool manager was opting to extend the reclaimed lead rather than protect it.

On the 12th of January 2014 Liverpool defeated Stoke City at the Britannia Stadium. At the time of kick off, Stoke had conceded seven goals in ten matches and Liverpool had not won a league game at the Britannia in the Premier League era. With 66 minutes on the clock, Liverpool were leading 3-2 having managed to reclaim the lead following a disastrous first half surrendering of a two goal cushion. At this point Brendan Rodgers decided to bring on striker Daniel Sturridge. Rather than protecting a lead that had already been so catastrophically lost barely a half hour earlier, the Liverpool manager was opting to extend the reclaimed lead rather than protect it.

The plan worked – just! Liverpool extended their lead, saw it clipped back again, and then finally scored again to end the game 5-3 winners with substitute Sturridge pivotal in both goals. Liverpool’s hoodoo at the Britannia was over, as was Stoke’s impressive defensive record there. More crucially, Liverpool had added to a long list of score-lines from the 2013-14 season that, collectively, could best be described as “absolutely fucking ridiculous”.

It is a list that feels wholly unnatural and false. Spurs away 5-0. Swansea at home 4-3. Spurs away 4-0. Everton home 4-0. Everton away 3-3. United away 3-0. Arsenal home 5-1. Norwich 2 Liverpool 3. Cardiff 3 Liverpool 6.

Fulham 2 Liverpool 3. Crystal Palace away 3-3. Stoke 3 Liverpool 5. Scoring 101 goals, this was the most prolific scoring season in the club’s history. In Suarez and Sturridge Liverpool had the highly unusual distinction of boasting both of the league’s top two goalscorers.

But to dwell on the team’s mind-boggling attacking prowess is to tell only half of the story. Liverpool also “boasted” a defensive record that was worse than that of Premier League minnows Crystal Palace, with an astonishing half century of goals conceded (almost double that of Chelsea who finished behind the Reds in third). In short, to state the obvious, Liverpool’s matches contained lots and lots of goals. Regardless of which team was sticking the ball in the back of the net, the interesting point of note is that the ball was being stuck in the back often. Very often.

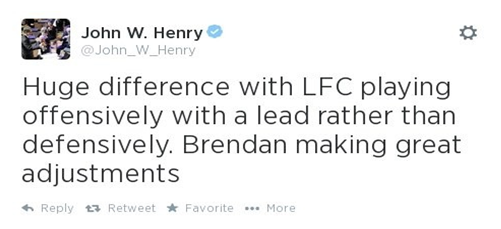

Three months prior to the Stoke game, Liverpool had comfortably seen off an inadequate Fulham side at Anfield with a 4-0 victory, prompting the above tweet from Liverpool owner John W Henry. He was praising the team’s ethos for attack when in a leading position, as opposed to a “sterile domination” approach, or “closing the game out”. Why had Liverpool beaten Fulham 4-0? Why not 2-0, or 2-1, or 1-0? Perhaps the most obvious answer is that Fulham managed to combine breathtaking ineptitude with an abominable lack of effort. But looking at the tweet above, and at Liverpool’s results in a wider context, the broader reason was something far, far more interesting. Here was Brendan Rodgers, holding on to leads in matches by trying to extend that lead rather than kill the game off. Not only that, but the owner of the club was directly praising his strategy.

The old-fashioned way of describing such a strategy is to say “attack is the best form of defence”. Was that the thinking of Brendan Rodgers and the Liverpool players? Maybe. But before we blithely dismiss these events with an old cliche, it’s probably worth taking a moment to see just how unusual these events were.

Part 3. Craziness in Context.

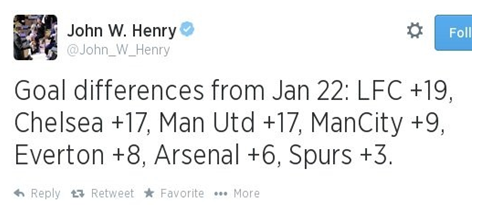

By the time the 2013-14 Premier League season had drawn to a close, Liverpool had attained the remarkable distinction of climbing from 7th place in the league to 2nd. It was an accomplishment marked by some of the most exciting, free flowing football seen in England for a long time. Liverpool had however not managed to combine this free flowing adventure with ruthless defensive capability, ultimately conceding, as mentioned above, more goals than lowly Crystal Palace. In the end this cost Liverpool the Premier League title as they lost out on the final day of the season to big spending Manchester City.

Only a short time earlier back in late March of 2014, after Liverpool had beaten Tottenham Hotspur 4-0 at Anfield, the Reds had a “Goals Per Game” average of 2.75. This was thanks to plundering 88 goals from 32 matches at that stage. As things stood at that point, with Liverpool having only six games left to play in the whole season, their goal scoring feats simply made the jaw drop. The last team to better Liverpool’s 2.75 goals per game average (as it then stood) over the course of a top flight season were Spurs’ north London rivals Arsenal.

At this stage you may be thinking… “That’s impressive, because it’s a decade now since that great team of Henry, Pires, Viera etc. What a side that was!”

No, not that Arsenal team.

“That’s even more impressive. If you have to go as far back as the 1998 Arsenal team that’s really a whole generation of football. Bergkamp, Anelka, Overmars. Double winners. Well, no shame in not beating their record. They were a force of nature as an attack.”

No, not that team either.

“As far back as the Rocastle, Smith, Davis, Thomas, Limpar side under George Graham? That side’s achievement was so iconic it was made into a book by Nick Hornby, Fever Pitch. And even a film!”

No, not that team either.

“The early 70s Arsenal side? Bertie Mee’s 1971 double winners?”

Nope, not them.

“Well they didn’t do much in the early sixties. Is this statistic correct. They are Arsenal’s best sides post war”.

Who said anything about post war?

Try the 1932-33 (Nineteen Thirty Two To Nineteen Thirty Three) Arsenal side, managed by the great Herbert Chapman, and led by striker and goalscorer extraordinaire Cliff Bastin. So that’s just the seven years before the outbreak of World War 2! And although their rate of goal return declined slightly in the remaining few games, it was nevertheless true that at the end of March 2014, if you wanted to find a top flight team with a higher season average of goals per game than Liverpool, you would have to go back to a time when Bob Paisley was 13 years old.

Clearly, that’s a difficult stat to comprehend. What makes it even harder to reconcile is the fact that this was a team that barely a year earlier had spluttered to a 7th place Premier League finish, with question marks over the manager’s tenure (not least, somewhat infamously, by yours truly).

Perhaps the best way to contextualise this statistic is to note that in 1933 England were not even members of FIFA, because the British authorities (as the official history of the PFA puts it) “deemed the standard of play abroad as too poor”. Let the magnitude of that statement register for a moment. England didn’t even bother playing against Brazil because they thought they were shit. That’s how long ago it was that someone had a better goal scoring record than Liverpool as things stood at the end of March 2014.

Wow.

Whilst Liverpool’s goals per game eventually tailed off slightly to 2.66, it was nevertheless still enough to rank this Liverpool side 9th in the all time list of the most free scoring sides in English football top flight history. Not only that, but Premier League Golden Boot winner Luis Suarez had missed Liverpool’s first five games of the 2013-14 season for biting an opponent. In the five games he missed at the start of the season, the Reds only averaged a solitary goal per game. This means that in the 33 league games the Reds played after his return they scored 96 goals in 33 games. An average of 2.91 goals per game. Only two teams since World War 1 (that’s “One”) have bettered that. An average of 2.91 goals per game over the course of a full season works out at a total of 110 goals.

Simply put, Brendan Rodgers had made Liverpool so attacking that the quest to overhaul 20 League titles from “that lot down the East Lancs Road” now seemed quaint and almost parochial. The Reds were bearing down on records that stretched back to an industrial age when the Manchester Ship Canal was still only beginning to shift economic power eastwards.

Part 4. Charlie Adam gets on base.

“Virtually every player transaction now has a dollar sign in sports associated with it. You have to have analytics”

“I don’t think we were really prepared for buying a team in the English Premier League…we’ve learnt a lot of things that I never thought I would have to learn about.”

— John Henry at The Sloane Sports Analytics Conference

In November of 2010, French executive Damien Comolli was appointed “Director Of Football Strategy” at Liverpool by John Henry and Fenway Sports Group. A friend of Oakland A’s General Manager Billy Beane, Comolli was seen as Beane’s spiritual heir in the world of soccer. Like Beane, who had used “Sabermetrics” to gain an edge in the world of Baseball, the Frenchman was known for employing unusual scouting metrics to unearth undervalued players. A kind of Sabermetrics for the world of football.

Sabermetrics was a term coined by Baseball statistical researcher Bill James. It is derived from the acronym SABR, which stands for the Society for American Baseball Research. At it’s heart, it is an attempt to discover empirical, objective facts about Baseball. In Michael Lewis’ book “Moneyball” (later turned into a movie of the same name), Beane searched for metrics which were underutilised in the sport, most famously on-base percentage among hitters. “Embracing the unconventional” was how Henry had described FSG’s approach when taking over Liverpool. Beane, eschewing traditional metrics like batting averages, had done exactly that at Oakland, and the results had been spectacular.

In 2002 John Henry and Tom Werner, fascinated by the work Beane had done in Oakland, tried and failed to hire him as General Manager for the Red Sox. Their ultimate failure to recruit Beane, however, did not prevent the Red Sox from going on to win three World Series championships, including their first (in 2004) for 86 years. In a neat parallel, this World Series win also provided the setting for the American version of the aforementioned Fever Pitch movie.

And so in 2010, Damien Comolli began to apply the same approach to transfer dealing at Liverpool. Players like Charlie Adam and Stewart Downing were highlighted for statistics that were felt to be undervalued by the sport at large. In the case of Downing, his well above average crossing percentages at Aston Villa had stood out. After signing Charlie Adam, Comolli had said “We were looking with Kenny at data on how well Blackpool did at set pieces last season. If you look at them, they are at the very top of the Premier League. That’s another reason to bring him in”.

In both cases attributes had been highlighted that appeared to be answers to a major, burning question. How do you get the best out of Liverpool’s 35 million pound striker Andy Carroll? The question which seemingly hadn’t been asked was whether crossing the ball for a big man to head into the goal was a strategy that would work at the top level of the game.

In the end, it wasn’t. Both Comolli, and then later manager Kenny Dalglish, were sacked – thanks primarily to under-performance in the Premier League. But with the dust settled, the generally negative consensus on Comolli’s record could be seen as not entirely fair. The club’s greatest signing of the era, Luis Suarez, is perhaps partial redemption for the metrics Comolli had employed. As Comolli himself had put it, “For Luis, I looked at the stats over the last three years, notably the number of games played which is an important factor. We turn enormously toward players who don’t get injured. We also took into account the number of assists, his performances against the big teams, against the smaller clubs, in the European Cup, the difference between goals scored at home and away.”

What chance a metric for games missed due to biting players on the other team?

Some time after being fired from his job at Liverpool, Comolli gave an interview in the Times in which he recalled make or break talks with the the club’s ownership. “I went to Florida in March to stay at John Henry’s house for three days,” recalled Comolli.

But a holiday at the beach, sunbathing and playing golf, it was not. Henry and club chairman Tom Werner were not happy, and they left Comolli in no doubt as to why.

Werner had asked Comolli about then manager Kenny Dalglish. “Do you think Kenny is the right person?”, came the question. “Definitely” replied Comolli, and John Henry agreed. Comolli explained to the two men that he felt Dalglish deserved more time and reiterated his opinion that it was not wise to sack Dalglish.

But the men who ran Fenway Sports Group seemed less interested specifically in who was or was not going to be in the manager’s hot seat. Instead they were preoccupied with something else. Something Comolli had not expected. “They thought we were not playing enough positive football, so we had a discussion about that” said Comolli. “They were not happy…”, he went on, “…about the fact that we were not scoring enough goals”.

Part 5. I Bring scientists, You Bring a Rock Star.

“MALCOLM: You see? The tyrannosaur doesn’t obey set patterns or park schedules. The essence of Chaos.

ELLIE: I’m still not clear on Chaos.

MALCOLM: It simply deals with unpredictability in complex systems. The shorthand is the Butterfly Effect. A butterfly can flap its wings in Peking and in Central Park you get rain instead of sunshine.

Ellie gestures with her hand to show that this has gone right over her head.”

– Jeff Goldbum and Laura Dern in a scene from Jurassic Park.

The power of Pascal’s triangle to show the probability of any combination of heads and tails in a given number of coin tosses lies in the fact the coin toss is a discrete event. Independent from the coin toss before or after, its discrete nature fits neatly into a model. It may be the simplest probability model imaginable, but therein lies its elegance.

As discussion raged about the application of Sabermetrics in football, the quintessential debate centred around the fundamental differences between the two sports. Like a coin toss, baseball lends itself to data modelling by virtue of the fact that it can pretty much be split into independent, discrete events. The effect of one pitch on the next, or one hit on the next, whilst not completely zero, is low enough that certain assumptions can be made to extrapolate empirical facts about cause and effect in the sport. In football of course, with a few exceptions, the same cannot be said. The fluidity of the game, interchange of positions, randomness and near infinite number of unique situations make it almost impossible to decipher which metrics are the most meaningful. Whilst perhaps not impossible in theory, arguably impossible in practice.

Clear-cut chances created, assists, key passes, tackles, pressing actions, goals scored, headers won, one-on-one successes, interceptions, aerial duels, ground duels, pass completion, pass accuracy. The list goes on, and on and on. Each successive recording of one metric occurring in a scenario utterly unique and different from the last. If a player has poor pass completion stats, does that mean he has poor accuracy when passing the ball, or are his team mates poor at moving into space? How do you tell the difference, and what do you use to test it? Heat maps? If so what kind of heat maps? Even if you can somehow establish that he is in fact empirically good at passing, is this a valuable attribute? How valuable? How do you know?

The sheer volume of information recorded now in any one game by organisations such as Opta shows that the above list of metrics is merely the tip of the iceberg. As Jeff Goldblum had said in Jurassic Park, this was the “inherent unpredictability in complex systems”. Perhaps the exact same inherent unpredictability that had made football the most popular sport on the planet by many orders of magnitude. And whilst Dr Malcolm’s line about chaos theory went over the head of his paleontologist companion Ellie, it was a point that was not lost on John Henry. When asked, for about the 800th time, about “the use of Moneyball in football” Henry had replied… “Everyone is fixated on Moneyball or Sabermetrics. But football is too dynamic to focus on that.”

Nevertheless, it didn’t stop an avalanche of statistical analysis flooding the game, with the online community (including contributors to The Tomkins Times), often at the forefront of finding new and interesting ways to correlate seemingly obscure data with on pitch success. It was indicative of an era where statisticians were becoming the quasi rock stars of the day. “I bring scientists, you bring a rock star” was how Richard Attenborough’s John Hammond put it when describing Goldblum’s “chaotician” character. And whilst maybe not exuding the same charisma, the likes of Nate Silver have indeed become celebrities (if not quite rock stars) by expanding the use of Sabermetrics to other fields. In Silver’s case this was most notably by predicting, with almost spooky accuracy, the 2012 US Presidential election.

The sea change was nowhere more evident than in football. The growth of this analytical, data savvy sub-culture, along with it’s inherent struggle to grasp the game’s fundamental secrets, were summed up beautifully by Brian Phillips of Slate Magazine, when he said..

“The notion of soccer as a kind of quaint, starry-eyed endeavour that can’t be explained by the numbers is a little outdated. There’s just one problem with the sport’s newfound sophistication, which is that soccer happens to be a quaint, starry-eyed endeavor that can’t be explained by the numbers.”

As for FSG’s first appointment – Damien Comolli, his experiment to bring the world of sabermetrics to Liverpool had failed. The team had floundered in the Premier League, and Comolli had been sacked. Football had been shown to be too fluid a game, too random an endeavour and too enigmatic a spectacle to pin down mathematically. Analytics in football had been defeated.

Or had it?

Part 6 Carpet Baggers

“These guys are nothing more than carpet baggers” – JoeP, TTT reactionary.

“One thing I can guarantee is that they (Fenway Sports Group) have a plan and they will implement it.” Jeff Reed, American TTT stalwart.

From an early age John Henry had shown a proclivity for understanding probability and the numbers underpinning it. Shortly after publishing a paper with an instructor at UCLA about how to win at blackjack, he has said that at the age of 22 he was thrown out of a Las Vegas casino. The reason for this premature ejection? Card counting. Card counting is a casino card game strategy (used mostly in games like, funnily enough, blackjack) where a player or players keep a running tally of all “high” and “low” valued cards seen by the player. By doing this, players were able to more accurately predict whether the next card would be higher or lower. That is to say – predict with a higher degree of accuracy than is achieved from random guessing. This shifting of the odds (however slightly) in the favour of the player empowers him or her to bet more with less risk when the count gives an advantage. In turn it also allows the player to minimise losses when observing an unfavourable count.

Card counting is still technically legal in the United States but is frowned upon by casinos for obvious reasons. The popularity of a game like blackjack, and the profit accrued from the vast number of non card counting players, easily makes up for any losses that may be incurred from “advantage players” like the young John Henry. For this reason, Casinos prefer to keep blackjack as a casino revenue stream, and simply ban/throw-out those who appear to perform better than random guessers. Whilst the image of a gangly young man being escorted across a casino floor by a Joe Pesci-style enforcer might sound mildly amusing, being a math (Maths) nerd has served Henry well in the years since.

When trading commodities after inheriting the family soybean business, Henry looked for trends in markets that belied the underpinning market conditions. Henry’s philosophy was that, broadly speaking, people were trend followers reacting to certain events in ways that were essentially predictable. “Markets are really people. If you make a certain type of statement, you can make a pretty good prediction of how George Steinbrenner [longtime principal owner and managing partner of Major League Baseball’s New York Yankees] will react” Henry remarked.

The key to Henry’s thinking was to recognise the extent to which trends had arisen simply for the sake of people following a trend. If the world believed the price of commodity X would rise, was that belief born out of some external, empirical logic, or were people believing it simply because everyone else was believing the same thing? If the latter, that could indicate that the market value of commodity X was artificially inflated. Self-fulfilling prophecies in the market were prone to being nothing more than temporal distortions. Henry knew this and saw that what was good for the market was good for the world of baseball.

There is a scene in the movie Moneyball that crystalises the potential folly of trend following for its own sake. Brad Pitt’s Billy Beane, seated around a table of old-school baseball scouts, responds to concerns that a potential new signing has had copious off-field problems. “His on-base percentage is all we’re looking at now and he gets on base an awful lot for someone who only costs $285,000 a year” says Beane. In Baseball, the use of batting averages to effectively judge a batter’s worth was a trend born of received wisdom. Beane knew this, and John Henry later knew this too when he tried to bring Beane to Boston.

In Oakland, the unconventional had been embraced, and the rest was history. The old school scouts seated with Beane at the table were trend followers. To a degree, they were trend followers who followed those trends simply for the sake of following a trend. The very essence of received wisdom. It took a certain perspective to see through it, ultimately originating from outside professional baseball by the likes of Bill James. Using something like batting average as a reliable metric to predict baseball success was, at least to guys like Beane, Henry and James, shaky.

“The goal shouldn’t be to buy players, what you want to buy is wins. To buy wins, you buy runs. You’re trying to replace Johnny Damon. The Red Sox look at Johnny Damon and they see a star worth seven point five million a year. When I look at Johnny Damon, I see an imperfect understanding of where runs come from.” – Jonah Hill as Peter in Moneyball.

John Henry, when discussing anything and everything relating to his ownership of Liverpool Football Club, had shown an abnormal predisposition towards attacking play, and goals in particular. When describing the decision to replace Roy Hodgson, Henry was unequivocal. “We knew we wanted to change the type of football we were playing, we wanted to change to a much more positive … philosophy” he said.

Was Henry saying he wanted Liverpool to “buy goals” in the way Peter Brand (Hill’s semi-fictional character in Moneyball) had told Beane to “buy runs”?

Part 7: I will fight for my life

“Per aspera ad astra” (through adversity to the stars) – Brendan Rodgers

Almost two years after Hodgson had been dispatched (whatever became of him?), and after the failed transplant of Sabermetrics onto the world of football courtesy of Damien Comolli, Liverpool were in the market for a new manager. Enter Northern Irishman Brendan Rodgers. At Swansea City Rodgers had achieved an unusually high possession percentage statistic (the highest of every team in the division bar champions and billionaires Manchester City) whilst managing a team with the lowest wage bill, in relative terms, of any in the history of the Premier League.

Before his appointment, Rodgers had presented to John Henry and Liverpool Chairman Tom Werner a 180-page dossier on his plans to transform the fortunes of the beleaguered Premier League giants. Rodgers described his manifesto in plain terms. “The vision is simple – firstly to win the most trophies we can… the second is to play attacking, attractive football to win games”.

Brendan Rodgers is an attack-minded coach, favouring an ambitious, expansive style of football. Almost immediately after taking over at Liverpool he had started to instil in every player the possession-focused philosophy that had served him so well at Swansea. A feature of Rodgers’ management was to free his players from the burden of making a mistake. As he had done at Swansea, Rodgers publicly took the fall for individual player mistakes, citing his imposition of extreme passing for what were deemed inevitable teething problems. Even in his first competitive game in charge he had done exactly that. A mistake from Martin Skrtel had gifted a win to West Bromwich Albion, but Rodgers was at pains to stress that this was nothing more than inevitable teething as players learned his system. And if this meant that Skrtel sometimes looked like a polar bear on ice attempting neat, triangular interplay on the edge of his own area, then so be it.

Gradually, towards the end of the 2012-13 season, Liverpool began to click. At Newcastle United, even whilst missing the talismanic Suarez, Liverpool put six past Alan Pardew’s men without reply. It was the club’s joint-biggest margin of victory in an away league match since 1896. But as the team’s logic-defying attacking form continued into the extraordinary 2013-14 season, one giant looming problem remained. The defence. Or perhaps more accurately, the chronic inability of Liverpool to stop opponents from scoring goals. Lots of them.

As any logical, sensible person would, Rodgers saw the 2014 January transfer window as the perfect opportunity to rectify Liverpool’s defensive shortcomings. For once the Liverpool management, the media, the fans, the bloggers, the analytics guys, the lunatics on twitter…, everybody was of the same opinion. Liverpool had to get players who were better at defending. Not just at full-back and centre-back, but also in midfield. The club at the very least, it was thought, needed to start by purchasing a specialist defensive midfielder.

The Reds did not really have an ‘out and out’ defensive midfielder other than Lucas Leiva, who had suffered more than his fair share of injuries. This meant that, for many, all that remained unanswered was who were Liverpool going to buy to play in those defensive positions? And which position would be prioritised first?

Excitement rippled through the fan base when French defensive midfielder Yann M’Villa was spotted at a Liverpool away game. It appeared to be only a matter of time before the team that was breaking scoring records for fun, but also leaking them for slightly less fun, moved heaven and earth to find defensive reinforcements.

Then, on the 20th January 2014, Liverpool made an offer of around eight million pounds to Swiss club Basle for Egyptian attacking winger Mohamed Salah. Somehow, the team with the best scoring record in the Premier League (but also a “goals against” column that recalled the horror of Ruddock and Babb), were prioritising the signing of an attacking Egyptian winger from the Swiss league. To many onlookers it was nothing short of madness.

Brendan Rodgers had clearly noticed the problems in Liverpool’s defence, and was anxious to rectify them. But the rest of the FSG installed transfer committee – Head of Recruitment Dave Fallows, Head of Performance and Analysis Michael Edwards, and supposed deal broker Ian Ayre – were prioritising the signing of attackers. As it happened, Liverpool were gazumped for Salah. And as usual, it was by Chelsea sugar daddy Roman Abramovich, who offered way more than Liverpool’s valuation for the player in both transfer fee and wages. In short, the Salah deal was dead.

And so as the January window drew to a close, fans, media, onlookers and anyone with a passing interest expected Liverpool to finally deliver what must, indubitably, have been priority all along… defensive reinforcements. And, almost like clockwork, the Liverpool hierarchy dumbfounded the watching world of football once more, as Ian Ayre was sent on the eve of the deadline to Kiev to sign attacking left-winger Yevhen Konoplyanka.

Once again it was a deal which fell through on the whim of an oligarch – this time Dnipro’s owner refusing to sell – and Liverpool ended the January transfer window empty-handed. As fans bombarded the internet seething with contempt for yet another seemingly “botched” transfer window, underneath the hyperbole was a lingering question. Why were Liverpool acting like a man spending all his time and energy making improvements to his state-of-the-art, luxury kitchen, whilst at the same time his bathroom was flooding and getting worse by the minute? It appeared thoroughly bizarre.

FSG’s Liverpool hierarchy seemed to be acting on information that the watching world of football had not been made privy to. Why was John Henry preoccupied with Liverpool being attack-minded and positive? Football was of course all about scoring goals. That much is obvious. But it is also about defence. About stopping the other team from scoring goals. Where were the tweets from John Henry praising defensive play? What trend had John Henry seen that was a trend for trend’s sake?

Quite simply, why was John Henry so utterly fixated on scoring goals.

Part 8. The Roaringly Obvious

“In all affairs it’s a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.”

— Bertrand Russell

In the wake of Comolli’s failure at Liverpool, and the ongoing debate about the use of analytics in football, two clear world views were becoming entrenched. In one camp was the world view of those searching for the mathematical holy grail of football. The secret formula. Football’s “theory of everything” that would unite the quanta of interceptions, pass completions and pressing action, with the more general and more special theories of how to win European Cups and league titles. In the opposing camp was the world view of those who saw analytics as an inevitably fruitless fool’s errand. Like trying to predict Central Park’s weather by analysing Dr Ian Malcolm’s proverbial butterfly wings. That inherent unpredictability in complex systems.

There was always of course the other, third world view. That of the football establishment, where any kind of original thinking is frowned upon. If Billy Beane had been frustrated by his colleagues’ antiquated fear of on-base percentages, he would have been astounded by the world of English football. This was a world where the Match Of The Day sofa regulars appeared to view outside opinions as some sort of affirmation of witchcraft. But the debate over analytics existed nevertheless, and it was going to take something extraordinary to settle the argument.

The record-breaking run of the Oakland As under Billy Beane was the ultimate vindication of using unusual, empirical metrics to define a baseball strategy. But what of football? How could the world of football reconcile its chaotic fluidity with uniform, rigid metrics? What was the consensus on which metrics mattered?

Bill Gerrard, Professor of Business and Sports Analytics at Leeds University, explained that, in fact, there was no such consensus – “In soccer, beyond the roaringly obvious….that scoring a lot of goals is generally a good thing…there is no such agreement to be found” he said.

But whilst Bill Gerrard was rightly pointing out that no agreement had been found, his namesake, Steven, was busy leading a Liverpool team to execute the strategy which contradicted this claim. Not the claim about any lack of consensus, but the other nugget, right in the middle of Bill Gerrard’s statement, hiding in plain sight. “Beyond the roaringly obvious… that scoring a lot of goals is generally a good thing”.

“..scoring a lot of goals is generally a good thing…”. Evidently, not as roaringly obvious as Bill Gerrard might think.

Could the perspective of an outsider help discover a truth that was all but invisible to those who had been immersed in the game for so long? Were the people who “knew football” so bogged down by minutiae that they couldn’t see the wood for the trees? By trying and failing to impose Sabermetrics on the world of football, FSG (and former card counter John Henry in particular) didn’t just learn that what worked in baseball would not work in the fluid, random world of football. They also learned why it didn’t work. And only by stumbling upon the quintessential difference between baseball and football, courtesy of Damien Comolli, were they able to see one tiny, yet striking, common characteristic shared by the two sports.

In the battle of world views surrounding the beautiful game, it was indeed going to require something extraordinary to settle the argument. And, in 2014, extraordinary is exactly what Liverpool delivered.

Part 9. Twenty More Goals

“I’m looking to bring another twenty goals into the team” Brendan Rodgers in the summer of 2013

In the build up to the momentous 2013-14 season, Brendan Rodgers was on a pre-season tour of Australia with the Liverpool team. After a year in charge, the signs were that his tactics were starting to click. Liverpool had become a more expansive, ambitious side and had noticeably been putting teams to the sword, in particular the division’s weaker teams. It was on the Melbourne leg of this tour that Rodgers sat down to give an interview with popular Liverpool podcast The Anfield Wrap. In the interview Rodgers was asked about concerns over Liverpool’s apparent inability to defend crosses and track opponents running from midfield. In reply, Rodgers explained some of the improvements that had already been made.

“The season before I came in, we were deemed a very, very good defensive team. And what we did (this last season) is we only conceded three more goals than we did the previous season, yet we went from 49 goals scored to 71 goals. Which is quite a big turnaround in terms of the numbers”.

In the same podcast, host Neil Atkinson had picked up on Rodgers’ declaration in another interview that he intended to add yet another twenty goals on top of the tally that Liverpool had achieved in the 2012-13 season. He had also picked up on the team’s apparent proclivity for winning by big margins against weaker teams. “Strong results against the bottom ten, ratcheting those points up” was how Atkinson put it when discussing targets for the coming season. “Absolutely” was Rodgers’ candid reply.

Atkinson went on …. “You mentioned earlier about increasing the number of goals….For once the fixture list has been kind to us.. you look at the first 8-9 home games, and they’re all against sides you’d expect to finish in the bottom thirteen, apart from Manchester United. Have you deliberately pushed the players harder in training… in order to really go at the start of the season, to take those opportunities, to take those points that are available in the sort of games which at the back end of last season we did really well in? Are you targeting these games thinking ‘these are games where we can really rack some points up early’?”

“I totally agree” replied Rodgers.

Rather than being overly respectful to weaker opponents, or giving the politically correct reply that no game would be easy, or they would take things one game at a time, Rodgers had been much more forthright. He was openly admitting that Liverpool would target the games against the weaker teams to try and capitalise and make a strong start to the season. Whilst he ultimately also went on to acknowledge the importance of doing well against top 4 rivals, the admission was still tacit.

Whether Rodgers and Atkinson knew it, and regardless of whether or not they cared, they were describing a real world example of an asymmetrical, lop-sided version of Pascal’s triangle.

Part 10: Florida Revisited

“We absolutely annihilated England. It was a massacre. We beat them 5-4.” Bill Shankly.

It is a scene from Moneyball 2, the much anticipated sequel to the hit movie – Moneyball. Frenchman Damien Comolli (played by Ben Affleck) is in Florida. He is arriving at the grand entrance to a 27,000 sq ft estate in Boca Raton Florida, the vacation residence of Boston Red Sox and Liverpool FC owner John Henry (played here by Bill Nighy). It is March 2011 and Comolli has travelled across the Atlantic for a three-day sojourn to discuss his work at Liverpool. He is there to meet with Henry, but also with Liverpool FC Chairman, and Henry’s fellow Fenway Sports Group board member, Tom Werner (played here by Danny Devito. I don’t know. It doesn’t matter).

It is mid-afternoon. Comolli greets both men in the grand entrance hallway. He then follows them down a corridor, before turning into the main living room of the house. A white board and projector are set up on one side, but Henry and Werner offer Comolli a seat in a comfortable armchair on the opposite side of the room.

Henry: “Damien, thanks so much for coming, we really appreciate it”.

Comolli: “Sure – thanks for having me. It’s nice to be here. Your house is beautiful, and of course it’s nice to be in the sunshine”.

Henry: “Great!”

Werner: “Damien, we really wanted to get your thoughts on how you felt things were going over there. You’ve been in the job for over a year now, how are we doing?”

Comolli: “Well I think things are going really well. As you know we’ve made a fantastic signing in Luis Suarez. He is becoming one of the best players in European football and we are all really happy about that.”

Henry: “Yes absolutely. In fact I distinctly recall you citing his goals record against the weaker teams as the reason you signed him”.

Comolli: “Well, sure – that was one of the reasons. But we also looked at things like his injury record, number of assists, that kind of thing”.

Henry: “Right, right. I just remember the thing about the goals against weak teams for some reason”.

Comolli: “Yes, it’s true. That was one of the reasons.”

Henry: “Do you guys want a drink? Coffee? Anybody want some coffee?” Both men nod, and Henry picks up a phone on the side table next to his chair. Henry: “Could we get some coffee?”

Werner: “Let’s talk about Stewart Downing.”

Cut to an exterior of an empty tennis Court at the Boca Raton Estate. Time is passing and the sun is getting lower in the sky.

Cut back to living room. A maid is clearing away coffee cups, as a nervous Damien Comolli continues to talk.

Comolli: “… and the thing about Charlie, you see, is that his set piece deliveries are really quite extraordinary. The number of goals Blackpool scored last year from them is quite incredible…”

A long, awkward silence fills the room.

Werner: “What do you think about Kenny? Do you think he’s the right guy to get us where we need to be?”

Comolli: “Definitely”

Henry: “Absolutely.”

Comolli: “The job he’s, well we, are doing. It really takes time. To see those kind of improvements is not going to happen overnight. I think Kenny is the right man to take us forward. To be honest, sacking him at this stage I think would be premature. I don’t think that would be a wise decision at all.”

Henry: “Well he’s certainly turned things around, that’s for sure. It was looking a bit hairy with Roy there for a while.”

Werner: “Oh boy was it.”

Henry: “I think our biggest concern, when we look at how the team is playing now…. well, we’re concerned that the team isn’t scoring enough goals. We really want to see more attacking play.”

Comolli shifts uncomfortably, looking slightly perplexed.

Comolli: “Our first priority really was to make the team more solid. We have a very good defensive record.”

Werner: “I think we appreciate that. It’s just that we were really expecting to see a much more positive approach. A more exciting style.”

Comolli: “Well, I think if you were to ask anyone in football, anyone involved in the game for a long time, at the professional level, they will tell you that in order to build a great team you have to start with the foundation. You have to have the defence in place first. Once you have your back four, and I think we are very close to having it, then you can build on those foundations.”

Henry: “That makes sense. We are just concerned about the direction the team is headed in, you know, in terms of a positive, attacking style. We just want to be sure that we’re gonna see a lot more goals next season”

Comolli is visibly sweating, and furrowing his brow as he leans forward on the armchair.

Comolli: “That is certainly our aim. But it won’t happen overnight. You can’t just take a team that was in 7th or 8th position in the league, and suddenly have them start scoring a crazy amount of goals.”

Cut to exterior again. Night is falling, and the sound of crickets can be heard beneath the long Bermuda grass. Cut back to lounge scene.

Henry: “Let me ask you a question Damien”.

Comolli: “Sure. Anything.”

Henry: “We play 38 games in the Premier League each season. Roughly speaking, how many of those games would you say we were favourites in?”

Comolli: “Well, I’m not sure. It really depends. It depends on how strong the other teams are. Whether you’re playing home or away. Injuries, that type of thing.”

Werner: “But roughly speaking. What do you think?”

Comolli: “I don’t know really. I suppose that in more than half of them we would be favourites. We are 7th in the league right now, so I guess, technically speaking, we would be favourites against 13 of the other teams, so 26 games?”

Werner: “But you’d probably also be slight favourites in home games against some of the teams above you. Maybe.”

Comolli: “I suppose you could say that. We might be favourites against say Newcastle or Everton at home. Yes. Although they are both having good seasons. I think maybe, at a push, you could say 28, 29 games when we would be the favourites, but often only very marginal.”

Henry: “Well, I didn’t even really have the number that high. But even 28 games a season where you’re favourites – at 3 points for a win that’s 84 points.”

Comolli: “Well, it doesn’t really work like that. You can’t win every game you’re technically favourites in. The margins in football are so small. An unlucky deflection here, a sending off there, a few injuries, it doesn’t take much. Football is a low scoring game. Your goalkeeper can make a mistake and then you are in trouble.”

Werner: “And of course then there are the ties. Only one point for a tie. We’ve had quite a few of those.”

Comolli: “Well yes exactly. Draws are a common occurrence in football.”

Henry: “And you only get one point instead of three. You don’t even get half the points you get for a win, even though there are only two teams!”

John Henry walks over to the projector on the opposite side of the room. He dims the lights, and switches the projector on. On the screen is an image of a triangular array of numbers. They are arranged symmetrically, and at the top on the far left and right sides respectively, are the words “row” and “sum”.

Henry: “You know what this is?”

Comolli: “Is it a er… ”

Henry: “This is Pascal’s triangle.”

Comolli: “Ah yes”

Henry: “It’s a kind of a probability matrix. It can tell you the odds of getting any number of heads or tails from any given number of coin flips. You basically take the row number is the number of coin flips, then the er, the index of the number of that row, like say the 3rd number along, that’s the number of heads or tails you wanna know the probability of. And then the actual number that is written there, that – divided by the sum on the far side, that gives the probability of getting, you know, that many heads or tails from that number of coin flips”

Comolli tries to hide his incredulity. And just shrugs.

Werner: “The number on the right – the sum – that’s the total number of possible outcomes right?”

Henry: “Right!”

Henry looks back at Comolli.

Henry: “You know, this is a really simple model, it’s just for coin flips. It’s always 50-50 for a coin flip. But the thing is Damien, the thing that always struck me about Pascal’s triangle, is that the numbers on the right hand side, the sum of possible outcomes, they rise exponentially on every successive row. All the numbers on the left and right diagonal edges are always one, but the sum each time goes up exponentially. If you want heads every time you flip that coin, you’re odds are way worse for higher numbers of coin flips”.

Henry hits a switch and a different image is shown on the projector. It is another image of a triangular array of numbers. But this time, instead of a symmetrical triangle, the numbers are arranged in the shape of a lop sided triangle.

Henry: “This is kind of the same idea, but it’s for the probability of something that isn’t 50-50. In this case the odds are weighted slightly heavier on the right hand side. You know – on the other triangle we looked at, the left side is heads, the right side is tails, or vice versa, so it’s symmetrical. But here, you can see the numbers on the left are bigger than on the right. And the spacing is changed slightly to help illustrate that and show the unequal odds on each side. And you can see, the odds are really only slightly different in each case, but again, the increase is exponential. And because it’s exponential on each successive row, as you go down look at how much larger the numbers on the left are…”

Henry notices the two men are staring blankly at him. He switches the projector off and turns the lights back on.

Henry: “I had some other slides in there, one was of a pyramid, and some others but, lets leave the slides for now”.

Comolli: “I can see the point you are making John, and I think as we build the squad, over time, you will see improvements and we will be more likely to win the games we should be winning.”

Henry: “Well maybe I haven’t explained this very well. I think it can be quite confusing. So let me put it another way.”

Henry walks away from the projector and sits back down next to Werner. He leans forward.

Henry: “When I was in my early twenties, I was kicked out of a casino in Vegas.”

Werner: “Were you partying with Andy Carroll?” All three men laugh.

Henry: “No, no I wasn’t. I was cheating at blackjack. Well, I wasn’t cheating, I was counting cards. Which is technically legal, so it’s not really cheating. But of course they frown on it. I’m sure you’re familiar with the concept?”.

Comolli: “Yes absolutely. I knew someone once who tried it on Monte Carlo. They were kicked out too.”

Henry: “Right, exactly. But believe me when I tell you that when you’re 22-years-old, the money you can make by counting cards sure seems like a hell of a lot. At UCLA myself and another guy even wrote a paper on the best blackjack strategies. Of course the problem with casinos is that the better you do, the more likely you are to get thrown out.”

Comolli: “Naturally.”

Henry: “The point was, I got thrown out because I won a lot of money. And I won a lot of money because every time I counted the deck to be disadvantageous, I would bet tiny amounts, or just fold. And then every time I counted a good deck, depending on how good it was, I would bet more. If it was really good, I’d go all in. The odds only had to be slightly in my favour, but if I could stay in for enough hands, eventually I would win. Because the chances of me continuing to lose shrank exponentially with every successive hand. They had to, because the odds were in my favour.”

Werner: “And by the way, that’s why you should never play roulette. The zero is what kills you in roulette. It’s a sucker’s game. Seems like such a tiny disadvantage that people ignore it, but the zero is where the house makes all its money on the roulette wheel”.

Comolli: “You’re saying you want me to go all in? But how? Believe me nobody would like us to score as many goals as I do. We are trying to do that.”

Henry: “I think it’s more a case of what you’re willing to sacrifice to be able to gamble more. The key thing is this. You can even make your probability of scoring versus that of your opponent less, within reason, so long as you can increase the sample size.”

Comolli: “I’m not sure I follow.”

Henry: “Imagine you’re playing Russian roulette. There’s one bullet, but six barrels in the gun. So the chances of being dead in one round of Russian Roulette are…”

Comolli: “One in six.”

Henry: “Exactly. Now say we play a different game where we draw straws. There are three straws, one of which is short. If you draw the short straw, same deal as Russian roulette, you’re dead.”

Comolli: “Ok.”

Henry: “So the chances of getting killed in the straw game are…”

Comolli: “One in three.”

Henry: “Correct. So if I was to ask you which game you’d prefer to play, which would one would you choose?” Tom Werner butts in.

Werner: “Russian roulette of course.”

Comolli: “Right”

Henry: “Right. It’s obvious. But then suppose I changed the proposition in the straw game. It’s exactly the same. Three straws. Except we play the game 100 times. If, at the end of the 100th game, you have drawn the short straw more often than not, then you lose. Otherwise – you live. Then which game do you choose.”

Werner and Comolli together: “The straw game.”

Henry: “Precisely. So even though in the second, 100-round straw game your chances in each instant of the game are less than in Russian roulette, the cumulative probability means you should choose that game. So even though you have a little worse odds in each individual run of the game than you would in the Russian roulette game, you get more games to establish the underlying probability, which is in your favour in both cases. And since the probability changes exponentially with every additional run of the game, that more than outweighs a decrease in probability for a single go.”

Comolli: “I see your point, I’m just not sure how this relates to football, or Liverpool.”

Henry: “Well, You mentioned a while ago that you were concerned by how many crosses Glen Johnson lets into our box. And I guess what I’m saying is, rather than focus on how many goals that costs us, why not look at how many goals we score directly as a result of Glen Johnson letting his opponent cross the ball? I can think of at least three times we’ve gone straight down the other end and scored right after Johnson let his man cross the ball. Maybe we should just tell him to let the guy make the cross? Maybe it doesn’t matter if we get worse at defending crosses, or if guys run at our defence unimpeded, if it means there are more goals in each game? So long as, overall, any given goal that happens in a game is more likely to be scored by us than our opponent. And, as we talked about, in the vast majority of games it will be. Bottom line – I just want a bigger sample size. Beat all the teams below us, and a couple of the top 6 at home, that’s 28 wins. 84 points!”

At this stage, it is clear that all three men have said enough. They agree to retire for the evening.

Cut to the following morning. Comolli gets in a taxi outside the exit to the Boca Raton estate. The taxi then drives away heading into the distance. We hear Comolli make a phone call.

Unknown voice: “How did it go?”

Comolli: “Where do you want to start? These guys are really something else.”

Unknown voice: “Oh? Why do you say that?”

Comolli: “They don’t seem to really understand the realities of football.”

Unknown voice: “How so?”

Comolli: “They have this crazy idea that all we have to do is score a lot of goals. Lots and lots of them. I have all these metrics – crossing, assists, injury records…everything. But it’s as if they think there is only one metric that matters. Goals.”

Unknown voice: “Really? Did they tell you to breathe too?”

Comolli: “No seriously. They seem to have this bizarre fixation that, provided we don’t weaken too much, we can theoretically become a worse team, in a way, so long as the result is that there are lots of goals. Or something. It was very confusing.”

Unknown voice: “How can the team get worse but still score more goals?”

Comolli: “I think they meant by also conceding more? It just seemed as though all they cared about was there being a lot more goals. You know, like as if that would be easy. And somehow we would be much more likely to win.”

Unknown Voice: “What did you say to them?”

Comolli: “Not much I could say really.”

There is a pause as the car disappears over the horizon.

Comolli: “It’s just…they seem to think they can implement this kind of …kamikaze you might call it… attacking strategy. They think the team can just score 100 goals, and… well, for all I know those guys are sitting there in their beach house thinking Liverpool can challenge for the title, just by having high scoring games. I mean.. I did everything I could not to laugh.”

Comolli switches off his phone, and sighs to himself. “Ces américains… je ne sais quoi!”

* * * The End * * *

Disclaimer: Almost all of part 10 did not happen, with the exception of

i) Damien Comolli went to Florida

ii) John Henry wanted Liverpool to score more goals.

iii) Bill Shankly did say that Scotland “annihilated” England 5-4.

Our new book is out now, only on Kindle. (Paperbacks sold out.)