Since 1959 there have been no fewer than 124 occasions when Liverpool have gone three or more league games without a win. That’s an average of more than two per season.

Of these, 69 were runs of at least four games without a win (still slightly more frequent than one per season), while 34 were five or more games: a poor run you can expect to see roughly every second season (or once every 20 months) – and a run Liverpool were on going into the Spurs game, at which point I started researching this article.

On just eight occasions have the club gone six or more league games without a win since Bill Shankly first arrived, so Jürgen Klopp avoided that type of ignominy with the dismantling of Spurs; and only once – 2002/03 – has it run into double figures.

Two of the poorer runs came at the end of a season and carried over into the next first match of the following season – both times after easing up upon winning the league title – and there were two more occasions when it carried over for three games into the new season (albeit after unsuccessful seasons).

Thanks to TTT stalwart Graeme Riley’s phenomenal databases, and the results he extruded from them – and the help of Tableau Zen Master Robert Radburn – I’ve been able to look at the details of these runs. And further down the article you’ll be able to see Rob’s interactive graphic of all Liverpool’s results from the past 58 years, season by season, and select whether to look at league games or all competitions.

More importantly than just listing the runs, I’ve been able to look at whether these winless streaks were harbingers of doom – were they the signs of terminal decline – or were they merely blips on the way to greater things? After all, form is often a matter of ups and downs, right? Or does having a bad run automatically mean you are a bad team?

What’s interesting is that, often these runs were just a short while before great things happened. Which is not to suggest the logical fallacy that having crappy runs means you’ll therefore soon be great – as that is totally nuts; just that, in the past six decades, Liverpool have had most of their worst runs under their best managers, with the good times surprisingly around the next corner or two. So, a bad run does not automatically mean that you are a bad team, with no hope. It can often mean you’re an up-and-coming team, struggling for consistency.

And part of the problem of our view of a bad run is that, with the availability heuristic, we place more stock in what’s happening now, as if it is a permanent state. And as I also often state, it’s a problem compounded by how poor we are at foreseeing change. Whatever our current state, there can be an exaggerated sense that it will remain ongoing, when the data suggests otherwise. Equally, sometimes we may imagine positive changes that don’t come to fruition – future world-class young players who then vanish without trace. No one can perfectly forecast this stuff, which is why the game is still played in the first place. And having exciting young players is a good thing, even if you can’t guarantee they’ll achieve all that’s hoped for (just as a £60m signing can still flop).

Also, I’ve focused on league runs without a victory; but you can still have poor runs when you win the occasional game – you just lose a load more. But this is obviously a much bigger task to analyse. However, some of these get covered too, as there is one particularly interesting season where two really bad league runs occurred, with a strange pattern in between.

The Value of the Win

Now, it’s worth adding here that the importance of the win has shifted since the early 1980s, when two points for a win was raised to three. And whereas über-rich clubs with their mega-squads may now see teams win 70% of their league games, back then, with the same old team most weeks, Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley hovered at c.55% in the league over the course of their long top-flight tenures. Liverpool’s best manager in that sense, since Kenny Dalglish (first time around) hit a club-high of 60%, is Rafa Benítez, at 55%.

I’ve focused mainly on the league because cup games often mean a very uneven level of opposition: it could be Barcelona or it could be Havant & Waterlooville (whereas the top division is usually a more balanced selection of teams). As such, league games are probably a better all-round barometer.

Okay, what follows are the worst league runs since 1959 – analysis which starts below the Tableau visual. With the interactive graphic you can change the decade and the competition, to see different losing and winning runs.

#1: 2002-2003 – 11 Games DLDDDLLLLDL

Gérard Houllier

The worst run since the club was reborn under Shankly: eleven league games without a win.

What Happened Next?

Immediately: Liverpool won the League Cup, beating Manchester United in the final, two months after the winless streak ended. The Reds finished 5th, with 64 points – not disastrous by today’s standards, but a pretty big fall from the 80 points of the previous season (and in the days before the mega-clubs of Chelsea and Man City were financially “doped”).

Longer term: the core of the team was absolutely fine – better than fine, even – and in many cases would go on to form the spine of Rafa Benítez’s side in Istanbul: Dudek, Gerrard, Riise, Carragher, Hamann, Hyypia and Baros, plus Smicer (and even Traore, heaven forbid). And, of course, Michael Owen, Emile Heskey, Stephane Henchoz and Danny Murphy were part of the squad for the next season too.

History tells us that during that terrible run Liverpool definitely had half a great side: Gerrard, Riise, Carragher, Hamann, Hyypia and Owen were all top Premier League players for a number of years, and all but Hamann and Hyypia were 24 or under at the time; Gerrard and Carragher would of course get better still. All but Owen, who left on a semi-Bosman to join Real Madrid, played key roles in the three years after Houllier was sacked, where the Reds won two trophies, notched 82 points and reached two Champions League finals.

History tells us that during that terrible run Liverpool definitely had half a great side: Gerrard, Riise, Carragher, Hamann, Hyypia and Owen were all top Premier League players for a number of years, and all but Hamann and Hyypia were 24 or under at the time; Gerrard and Carragher would of course get better still. All but Owen, who left on a semi-Bosman to join Real Madrid, played key roles in the three years after Houllier was sacked, where the Reds won two trophies, notched 82 points and reached two Champions League finals.

Reasons: Some bad buys in 2002 were behind the slump – Diouf, Diao and Cheyrou all failed to live up to expectations. That’s £60m on three players in 2016 money, none of whom added anything consistently (Diouf had his moments before disappearing up his own anus). All three ended up as flops. Liverpool played quite a few cup games in amongst the run, including one of the League Cup semi-finals (a feature in Klopp’s two Januarys so far) and an FA Cup game, plus some UEFA Cup games at the start of the league slump.

However, this was an early warning sign that the Reds were losing their way under Gérard Houllier, who’d suffered a life-changing aortic rupture just 12 months before the team crashed.

A change of manager was clearly required by 2004. This was a team on the other side of its peak, in terms of what the Frenchman could get out of them; his 5th season, coming down the other side after two excellent seasons (the treble of 2001 and the 80-point, 2nd-place finish of 2002, with Champions League quarterfinals).

To go 11 league games without a win seems unthinkable now. The teams not beaten in that run were: Middlesbrough, Sunderland, Fulham, Manchester United, Charlton Athletic, Sunderland (again), Everton, Blackburn Rovers, Arsenal, Newcastle United and Aston Villa.

#2 – 1983-84 – 8 games DLDLLLLD

Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan

Liverpool’s second-worst run without a win since 1959, at eight league games. However, seven of them were at the end of Bob Paisley’s final season, with the title wrapped up (it was won by an 11-point margin).

So this is essentially a 7-game run under Paisley, as he bowed out, and the opening game of 1983/84. Therefore, this one can essentially be excluded.

1984-1985 – 7 games LLDLDDL

Joe Fagan

Liverpool’s greatest ever season – 1983-84 – saw Joe Fagan win the treble in his first year in the hotseat. But his second season fell apart just a couple of months into the campaign, on a seven-game winless run. That said, the opposition included Arsenal, Man United, Spurs and eventual champions Everton – so it wasn’t exactly an easy run on paper.

What Happened Next?

Immediately: It was October 20th, and the best ever Liverpool side were 17th in the table. 17th! Eleven games into the season and somehow it was falling apart. Winning four of the next five league games saw the Reds start to rise, and they kept rising until finishing 2nd in May; and did extremely well in Europe.

Longer term: The Reds made it to the European Cup final six months after that dodgy league spell, in a season that contained 64 games, including Independiente in Tokyo in December. Heysel provided an unthinkably horrible ending for Fagan.

The Reds – with much the same team, and a new boss in Kenny Dalglish – won the double the next season. However, even that side went five league games without a win in the middle of the season (December).

1974-1975 – 7 Games LDDDDDD

Bob Paisley

Oh dear, we would say now: he’s not cut out for the top job. He doesn’t have the charisma to replace Bill Shankly. He’s too nice. He wears slippers. A run of seven league games without a win? Not good enough.

But first, earlier that same season, there was a run of six league games without a win.

What Happened Next?

Well, after the run of six without a win came a super-strange strange pattern. After this winless streak, the Reds won, lost, won, lost, won, lost, won and … lost.

And with that last defeat began the seven-game winless streak in the league.

What Happened Next?

Immediately: After just four wins in 18 league games, Liverpool sat 5th in the table. (Liverpool have currently won nine of their last 18 games.)

Champions in 1973, FA Cup winners in 1974, this was not how Bob Paisley’s tenure was supposed to start after Bill Shankly stepped down. But the Reds then won six of the final eight games, to finish 2nd. Which back then, of course, was nowhere, to quote the old Liverpool maxim. But flippancy aside, it’s better than any position bar 1st.

Champions in 1973, FA Cup winners in 1974, this was not how Bob Paisley’s tenure was supposed to start after Bill Shankly stepped down. But the Reds then won six of the final eight games, to finish 2nd. Which back then, of course, was nowhere, to quote the old Liverpool maxim. But flippancy aside, it’s better than any position bar 1st.

Longer term: The following season the Reds won the league. The year after that they won the league, the European Cup and narrowly lost the FA Cup final. The year after that they won the European Cup again. The man with the cardigan and the slippers was onto something.

Six-Game Winless Streaks (League)

Next comes four runs of six league games without a win. I’ll cover these briefly; with Klopp thankfully escaping addition to this list this past weekend.

1964-1965. SHANKLY. DLLDLD. Side were defending champions, and went on to be champions the season after; and in this season they won the club’s first ever FA Cup, at a time when it was revered almost as much as the league.

1974-1975. PAISLEY. DDDDLL. Already covered earlier in the article, as part of two bad runs that season.

1992-1993. SOUNESS. LDDLDD. Not a lot good happened this season or the season after. But during 1992/93 there was the maturing of Steve McManaman, Rob Jones and Jamie Redknapp. Half of this team went on to challenge for the title under Roy Evans. The other half went to the glue factory.

2012-2013. RODGERS (+ 1 Carry over from Dalglish). LDLDLL.

A difficult start to life at Liverpool for Rodgers, although three of the games were against Man City, Arsenal and Man United. Liverpool played quite well in those games, but form remained patchy until the second half of Rodgers’ first season. His second season was explosive, to say the least.

Managers and Non-Win Frequency (League)

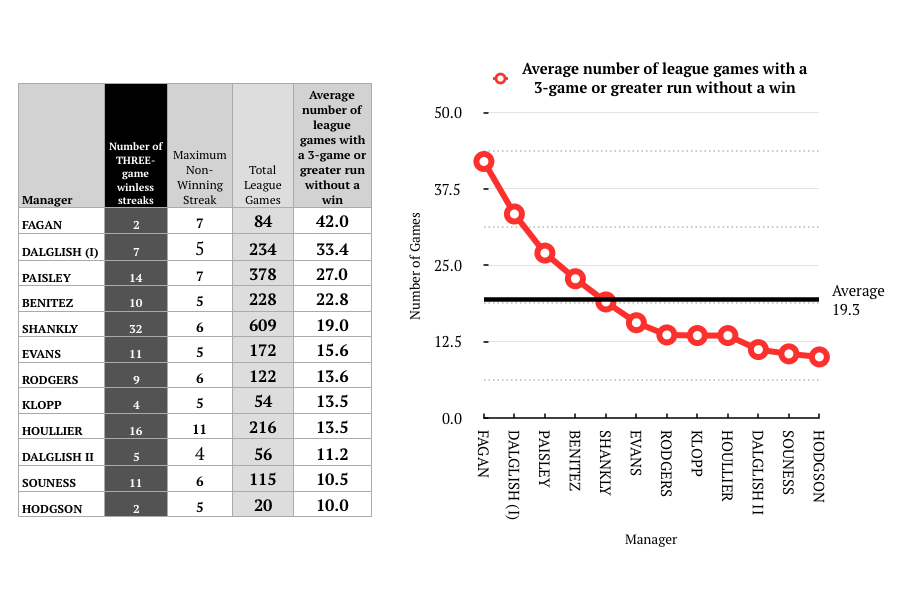

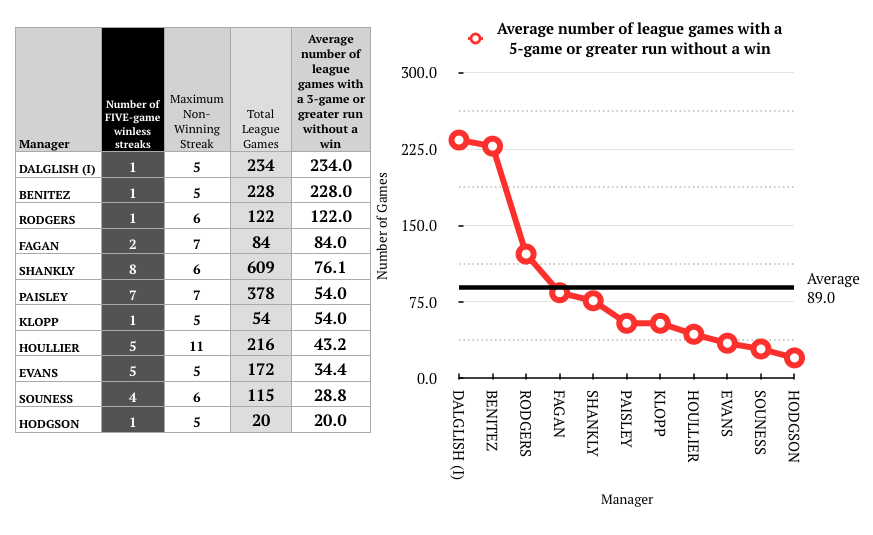

Bill Shankly had no fewer than thirty-two 3-game winless streaks, and eight five-games-or-more winless streaks. But he did manage for 15 years, starting in the old second division. Even so, that’s an average of one such run every 19 games.

He had a five-game winless streak in each of the first three years of the 1970s, before winning the title with a run that included four winless matches.

Jürgen Klopp has already endured four runs of three games without a league win, although one was his first three games (like Rodgers and Dalglish MkII). Two of the four occurred in January; and I can’t help but see the two-legged League Cup semifinals as an issue here, straight after the hectic festive period, to create nine and 10-game months.

Klopp has had one five-game winless run in the league, in his 55 games in charge – and it ended with a win over Spurs. This is pretty average; with Kenny Dalglish (first time) and Rafa Benítez way ahead, at just one five-game winless run in c.230 games each.

Brendan Rodgers only had one such spell in his 122 Premier League matches in charge. Roy Hodgson had one in his 20 games; and also two spells of three games without a win. He and Souness sit bottom of the 3-and-5-game tables. Dalglish first time around was imperious; second time far less so.

Conclusions

Form is a strange thing. Each result is subject to the vagaries of goalscoring and goalkeeping, of refereeing, and of how things just generally pan out on that particular day – the shape the game takes. On any given day you could meet a passive opposition that allows you walk all over them, or one that suddenly has a great game, or scores a great goal, out of nowhere. The opposition goalkeeper may have the game of his life, or he may drop one in his own net.

In longer runs the randomness should diminish, and a clearer picture emerge. (But even that doesn’t quite explain Leicester City.) Even a dozen games isn’t necessarily enough to see a regression to the mean. However, the good news, I think, is that even poor runs for Liverpool are often followed by success further down the line. Bad runs do not make for a bad side.

Liverpool’s best winning streaks, however, have not randomly appeared in the middle of otherwise terrible seasons. Nine wins in a row in all competitions is the best the Reds have managed this decade, coming in the narrowly-failed title bid of 2013/14; but at the same time, with cup games removed, the Reds won eleven league games on the spin. But every other season since the end of 2008/09 has tended to be disappointing; and since the departure of Benítez, the club has maxed out on runs of five consecutive wins in all competitions (2013/14 aside). The average for league wins, excluding 2013/14, is just 3.5 games in the other seven seasons since finishing 2nd in 2009.

Liverpool won 11 in a row in all competitions in 2005/06 (ten of which were in the league), yet strangely peaked with just five wins in a row in 2008/09, the best league season (points wise) since the Reds last won the league. That particular season shows that putting together several five-game winning spells is highly effective – that it’s not all about record-breaking runs like Chelsea recently went on; and that part of the rise to 25 wins and 86 points was due to being consistent – and only once failing to win more than two games in a row (a run of four starting at Stoke). Of course, if you can win 12 or 13 in a row you’re probably an outstanding team that’s going to win the league anyway.

Liverpool won ten in a row at the start of 1990/91, but then fell away badly, with Kenny Dalglish resigning in the winter – albeit the Reds still finished 2nd.

The 1980s was Liverpool’s best era in terms of double-digit winning runs: ten in all competitions in 1981/82 (for the first time in the period covered), but with cup games removed, 11 in the league – the joint best with 2013/14. For league games only, 1981/82 and 2013/14 sit top at 11 in a row, with 2005/06 the only other one to hit double figures since 1959.

The Reds also had ten wins in a row in all competitions in 1982/83 and 1986/87, and eleven in 1988/89 – a run that ended with the Hillsborough tragedy. (The final seven games of the rearranged season were squeezed into just three weeks, starting with a draw at Everton 18 days after the nightmare of the FA Cup semifinal. Even so, Liverpool had won 17 out of the previous 18 matches going into the head-to-head with Arsenal, including beating Everton in extra-time in the cup final. In the aftermath of the horror, it’s easy to overlook how good that team was – probably peaking then, before the key players hit their 30s.)

The run in the first half of this season – from Burton to Man City – was clearly the best (along with the end to 2013/14, up to the Palace game) in a decade, with just one defeat in 20 games, and 15 wins. So I think that’s a good sign – the high-water mark of what this team can achieve. And the poor spell is not necessarily a bad sign, if history is anything to go by.

But as ever, it’s about building on what’s working and trying to eradicate the problems. Add more like Mané, Matip and Wijnaldum in the summer (without losing key players) and the team can rise to the next level; end up with the equivalents of Diouf, Diao and Cheyrou and it could look very different.

This is a free article. To support our work (and keep the site running), and to read paywalled articles as well as join in the debate, subscribe here.