With Kenny Dalglish apparently in the running for the vacant manager’s job – or at least, throwing his hat into the ring – I thought I’d share the chapter on the Reds’ legendary no.7 from Dynasty: 50 Years Of Shankly’s Liverpool.

While I hold several reservations about his ability to manage at the highest level 12 years after he last took charge of a side (some listed here and here – along with some reasons why it might just work), I don’t think you can have much argument with his record first time around.

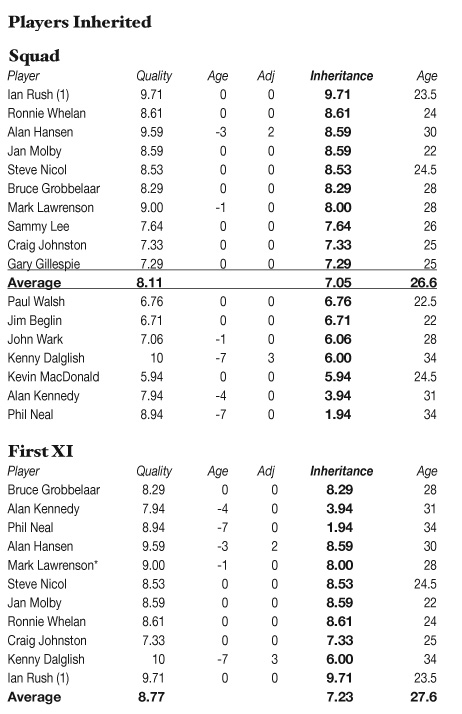

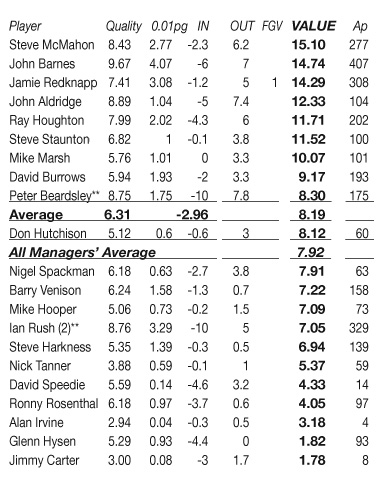

Note: There are a couple of tables that, despite an accompanying key, will not necessarily be 100% clear without having read the book itself. Briefly, the Quality mark relates to the average – out of 10 – awarded by the Brains Trust (journalists and long-time fans) for every player between 1959 and 2009. The Inheritance value was worked out by taking age into account. And the Value figure was a coefficient calculated from the Quality, fee paid, fee later sold for (or an equivalent mark if the player remained a valuable player into his 30s), and .01 point for every game played for Liverpool.

Introduction

It’s certainly far harder to judge where Kenny Dalglish fits in at the top end of the Liverpool management table than it is to judge him as a player. As the latter, he was simply the best –– the King. No argument. His six years as manager were also full of success, and in the middle of his reign, the football was resplendent, and at times breathtaking — almost certainly the most aesthetically pleasing seen in the club’s history. But his tenure didn’t quite reach the heights of Paisley’s, and he hadn’t had to build the club up like Shankly. Meanwhile, his six years marked the club’s exact exile from Europe, which removed one area of comparison, particularly with the man who had brought him to the club in 1977 and who dominated on the continent.

While Liverpool fans were not exclusively to blame for the European ban –– firstly, because the fans of other British clubs had caused plenty of trouble themselves in order to sully the reputation of English supporters, and secondly because the deaths of 39 Italians at Heysel came when a creaking old wall collapsed amid two fighting nations –– they did contribute to the dark ages of English football. By this point the best players had already started to move abroad –– most notably, technical players like Graeme Souness, Liam Brady, Ray Wilkins, Trevor Francis (and, er, Luther Blissett), with Chris Waddle and Glenn Hoddle to follow –– and the imports into England, bar the odd exception, were not of a similar quality. It meant that the top division was not at its strongest just a handful of years after the country’s clubs had dominated European competition. Even so, Dalglish’s job was to beat what was put in front of him, and it was not his fault that trips to Rome and Madrid were no longer on the agenda, and places like Plough Lane, Wimbledon, were.

The other question mark over Dalglish is the situation he bequeathed his successor. The Hillsborough disaster in 1989, in which 96 lives were lost, effectively marked the end of the great league-winning dynasty. One more title was bagged, in 1990, but Dalglish was feeling the strain. The team his successor inherited was ageing badly.

Situation Inherited

The day before the final at Heysel, Sir John Smith announced to the club’s directors that he’d appointed Kenny Dalglish as the new manager, following Joe Fagan’s retirement. To some it came as a massive shock, although a year earlier Graeme Souness had told a Scottish journalist that he expected Dalglish to be the club’s next boss. With Fagan the third, and final, remaining member of the original 1959 Boot Room to take the role, it would have to be someone from the next generation. All eyes were on Ronnie Moran, the most senior coach, with Roy Evans, still in his 30s, a less likely option. Chris Lawler was seen as having an outside chance, and from within the playing staff, Phil Neal was a strong candidate. But Dalglish was the man Smith wanted.

Liverpool were still the envy of England, but the situation at the club was far less rosy: Dalglish took the reigns in the immediate aftermath of the Heysel tragedy, when a shellshocked Joe Fagan, hoping to retire with a wonderful win, found his last game to be the stuff of nightmares. Quality was still very much in abundance on the playing staff in 1985. Graeme Souness had moved to Sampdoria in 1984, but otherwise all the key players from the phenomenal treble-winning side were in place –– including, of course, Dalglish himself. The player-manager aside, the squad included key men such as Alan Hansen, Ian Rush, Ronnie Whelan, Mark Lawrenson, Steve Nicol and Bruce Grobbelaar, plus Jan Molby, a player who hadn’t quite found his form in his debut season as Souness’ replacement, and who had struggled to hold down a place in the team, but who would go on to net 21 goals in Dalglish’s first campaign as manager. One player who presented Dalglish with a problem was Phil Neal, the club captain, who was upset at being passed over for the manager’s role. In an act of pettiness, he refused to call Dalglish ‘boss’. Before the subject had been raised, Neal told the press he didn’t have a future at Anfield; as a result he was stripped of the captaincy. He quickly took a move to manage Bolton.

Due to the post-Heysel exile, Dalglish is the only manager covered in this book not to take his team into Europe. The ban affected all clubs, and while Liverpool were seen as being to blame, the supporters of other clubs had played their part. A year earlier, also in Brussels, a Tottenham fan was shot dead and a further 200 held by police following a riot before the UEFA Cup Final against Anderlecht; the same year England fans had caused almost £1m of damage in Paris following defeat to France. To further highlight the trouble of the times, in 1986 five people were stabbed in a riot between 150 Everton, Manchester United and West Ham supporters on a cross-channel ferry, which was severely damaged and forced to return to England. But the rest of the English clubs returned to European competition in 1990, with Liverpool, who would have qualified for the European Cup, having to wait an extra year. By this time Dalglish had resigned and Graeme Souness was in charge. Europe was back on the fixture list, but alas the Liverpool of old had withered away in the interim.

Players Inherited

Key: Quality 0-10; Age = -1 point for every year from 28 onwards, eg -4 for 31 year-old, and -1 point from 30 onwards for keepers, eg -4 for 33 year-old; Adj = adjustments for players either exceptionally fit/unfit for their age, or soon to leave; Inheritance = total out of 10. Excludes players not part of first team picture.

In terms of Quality, the First XI, fresh from back-to-back European Cup finals, was still incredibly strong in 1985. But Phil Neal and Alan Kennedy were in the twilight of their careers, so replacements were needed. As a result of Neal moving to Bolton, Steve Nicol was moved to right-back. In Jim Beglin, Dalglish already had a player capable of filling the left-back slot, and before too long he was in the team, while Gary Ablett would emerge in 1986. Alan Hansen had turned 30, but was an especially good reader of the game. And of course, there was Dalglish himself, who had now turned 34. These age adjustments weaken the First XI Inheritance rating to an average of 7.23, a full point lower than the side Paisley inherited, and half a point lower than the side Paisley left for Fagan. So it was still a great side on paper, but some key players were beginning to edge over the hill.

While players like Paul Walsh, Kevin MacDonald and Jim Beglin were in the squad and ready to either fill in for, or replace, the older members of the side, none was at quite the same standard as his predecessor. In Dalglish’s first season, Hansen remarked to the manager that this was the worst Liverpool side he’d played in. Within a few months the Reds would land the league and FA Cup double. Even so, it was clear that some serious work in the transfer market would be needed before too long.

State of Club

Sir John Smith and Peter Robinson — two of the game’s sharpest administrators — were still running the show. Smith had phoned Dalglish prior to the team leaving for Belgium for the 1985 European Cup Final, and asked if he and Robinson could come visit him at home. “I said aye, that was all right,” Dalglish recalled. “Then they told me what it was about, and I said they could still come.”

Towards the end of Dalglish’s tenure, Noel White replaced Sir John Smith as chairman. Smith had been spending an increasing amount of time with Sport England, of which he was also chairman, as well as with his own business. It would be alongside White that Dalglish would sit and announce his resignation to the world in 1991.

Assistance/Backroom Staff

In 1985, Ronnie Moran and Roy Evans, like the floodlights, were still permanent fixtures at Anfield. Chris Lawler, appointed by Joe Fagan, was still in place as reserve team coach –– although he would soon be departing in acrimonious circumstances.

Perhaps the key involvement for Dalglish should have been that of Bob Paisley as an advisor — which is akin to having Leonardo Da Vinci on hand to teach you how to paint. Dalglish had stipulated that Paisley’s assistance would be vital if he were to take the role, and the club was able to persuade the great man out of retirement, on a two-year contract. But as it transpired, Dalglish would not need much help from his former boss.

A year into his reign, and with the 1985/86 double freshly under his belt, Dalglish began to make a number of serious changes to the back-room staff. With Tom Saunders retiring at the age of 64, Steve Heighway took over as youth development officer. Saunders would later return to the club after being elected to the board of directors in 1993, and assist future managers in their administration tasks, until his death in 2001.

Also in the summer of 1986, Dalglish appointed Phil Thompson onto the coaching staff. Thompson had been training at Melwood twice a week; the former Liverpool captain had moved to Sheffield United two years earlier, but was now finding himself out of the first team picture. Interestingly, Thompson was offered the role of managing the reserves in conjunction with also playing for the second string — a slightly strange offer seeing as Thompson, now in his 30s, had been considered not good enough for Liverpool in 1984, and now the same was felt at Sheffield United. It can only have been to offer support and guidance on the pitch, in the way Ronnie Moran had between 1966 and 1968. Thompson had been appointed a couple of weeks before Lawler was told his services were no longer required. That conversation only came about after Lawler, wondering why he hadn’t received his bonus when the other coaching staff had, went to see Dalglish. Naturally, it came as a massive shock to Lawler, and given that he hadn’t done anything specific wrong — no serious failings, no misdemeanours — he did not take it well. But Dalglish was reshaping the club, and the first sacking of a member of the Boot Room was not something he would shy away from in order to maintain his vision, even if he didn’t handle the situation particularly well. While he’d been successful with the reserves, Dalglish saw Lawler as too quiet, not forceful enough. The same could never be said of Thompson; in fact, he’d often be charged with being the opposite.

If sacking Lawler was a shock, then replacing Geoff Twentyman, the club’s chief scout, with another ex-captain, Ron Yeats, was an even more stunning move. Yeats, who also took on Saunders’ role of scouting missions to assess the opposition, had no prior scouting experience, and was replacing arguably the best man in the business. Twentyman and Saunders had been two of the club’s great unsung heroes after two decades’ sterling service, with Twentyman in particular responsible for bringing some of the club’s greatest names to Anfield.

Saunders, meanwhile, had brought through some talented locals, like Phil Thompson and Sammy Lee. If anything, in his first twelve years Steve Heighway would surpass the work of Saunders, and unearth the best batch of home-grown talent the club had ever seen. By contrast, Yeats had little chance of matching the incredible feats of Twentyman, and, after one more summer of astute dealing, the next 12 years would see a change in quality of the players recruited to Anfield.

Shortly before his departure, Twentyman recommended two more players: Peter Beardsley of Newcastle and John Barnes of Watford. A year later Dalglish would sign both. By that time Twentyman was a year into working for Graeme Souness at Rangers. Beardsley and Barnes would be the last great signings made by Dalglish, and only one more enduring talent arrived at Anfield in the next four years — Ray Houghon, snapped up later in 1987. Whether or not it was down to the managers — after all, a scout can only recommend players and leave the decision to sign to the man in charge — it is damning to note that, with the exception of Jamie Redknapp and Rob Jones, the players signed by the club prior to the arrival of Gérard Houllier were mediocre at best; not all were necessarily mediocre in terms of ability or what they had shown at their previous clubs, but for one reason or another none shone as expected when wearing the red of Liverpool.

Was that down to Yeats? It’s hard to say. He was heavily involved in the spotting of Sami Hyypia, and Didi Hamann was also signed in 1999, so he can point to later successes. But Liverpool weren’t finding great hidden talents in the way they had with Twentyman as the club’s eyes and ears.

Management Style

Upon Dalglish’s appointment, Graeme Souness explained that his good friend had an ingredient vital for success: he scared people with a growl, and sometimes with even just a look. As well as being respected as a player, Dalglish was a strong character who could command respect as a man. He was no soft touch, as his former team-mates would discover.

As a neighbour, Mark Lawrenson had shared a lift to training with Dalglish for a number of years, but once the Scot became manager the relationship changed overnight. Lawrenson, struggling with injury, had agreed to coach at a summer soccer school in Dublin on the opening day of pre-season training in 1985, and was instantly rebuked. The centre-back felt firmly put in his place, and accepted Dalglish’s punishment.

While possessing more of a sense of humour than his dour image portrays, Dalglish had a poor relationship with the press. Terse, taciturn, and at times just plain rude, he did not play the media game. The result was that journalists became more critical, and less likely to give him the benefit of the doubt before putting the boot in. While his approach was understandable — the press can be difficult for a manager to deal with, as well as having their own agenda — rubbing them up the wrong way just increases the criticism, which ramps up the pressure. It may lead to a siege mentality that can inspire success, but it can also foster a sense of negativity around a club.

Ironically, Dalglish would later be called upon by the media to offer his views on the club, and appear on TV as a match summariser. To his eternal credit, he tries to see things from the perspective of the manager, and refuses to land the low blows so common from a number of other ex-players.

Unique Methods

In a precursor to rotation, Dalglish liked to be flexible with his line-ups. He was trying to be unpredictable, rather than protect legs for a long campaign, although that may have been in his thinking too. He didn’t go in for the wholesale changes seen from all big clubs in the modern era, just one or two from game to game. At times there would be a settled side for a run of matches, but never in the manner of the past. He liked to omit Peter Beardsley against the more physical teams like Wimbledon and Arsenal, while Jan Molby would be shifted from a standard midfield role to playing behind the front two (Ian Rush, and either the manager himself or Paul Walsh), and then converted to sweeping behind the back four. In time Beardsley found himself sitting out more and more games, and his selection — or lack of — became a hot topic. It wasn’t always apparent why he was omitted — the forward was left out even when he was the top scorer in the country. The Geordie started to feel victimised, although he later admitted that he came to understand it was not personal, but tactical. The manager claimed that the player had a stress fracture during his final months in charge, which partly explained some of the omissions. Dalglish also felt that Beardsley needed to be more ruthless as a finisher, and it’s something the player himself agreed with. In and out of the side, Beardsley’s confidence started to crumble — but Dalglish was merely trying to pick the right team to win each game.

Dalglish also refrained from naming the team until shortly before kick-off; a method, like rotation, employed by Rafa Benítez. The players weren’t always happy with it, but it did serve to guarantee that no-one could ease off in the build-up to a game, and complacency couldn’t easily set in. Ronnie Moran, a member of the ‘old school’, felt the new development was a brilliant move — there was a lot more intensity in training, with 16 strong possibilities fighting to be in the next line-up.

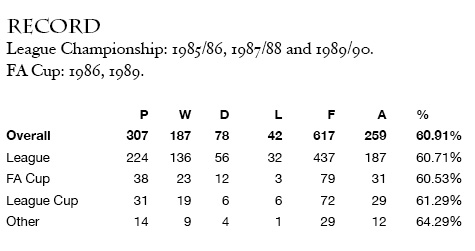

But of course, no method in football is fail-safe, and every philosophy involves weighing the pros against the cons. Dalglish was heavily criticised for his inconsistency of selection whenever the team lost, or hit a sticky patch of form, but his record over his six years in charge is testimony to the wisdom of his methods. Dalglish has by far the best win percentage out of all the club’s managers in the last 50 years, in both the league and across all competitions. Given that Alan Hansen felt the 1986 team was the worst Liverpool side he’d played in, and that many felt that the 1990 team wasn’t vintage either, that suggests Dalglish was doing something very right indeed.

Strengths

Initially, identifying and signing good players was Dalglish’s key attribute. And in many ways it needed to be. Not only were some of the players he inherited edging over the hill, and his star striker eyeing a move abroad, but some cruel injuries would rob him of a number of key players.

Kevin MacDonald, a key component in the double-winning team, was finally starting to look capable of growing into an inspirational midfielder when, in September 1986, he broke his leg; he would return to playing 18 months later, but the injury had taken its toll and he was not the same player. Jim Beglin, emerging as a fine young left-back, suffered the same fate: a broken leg in the same season; unlike MacDonald, he wouldn’t return to the first team even for a few token appearances. John Wark was another who broke his leg in 1986. Steve Nicol missed the whole of the second half of 1986/87, although returned to full health for the following season. But Mark Lawrenson was seriously injured at the back-end of Dalglish’s second season, with the defender approaching his 30th birthday. The Achilles tear ended Lawrenson’s career.

The biggest of all the departures in Dalglish’s time was when, in 1986, Ian Rush announced that he would be joining Juventus, effective from the summer of 1987. The deal, valued at £3.2m, was the most expensive in British football history. While a surprise in many respects –– unlike Kevin Keegan a decade earlier, Rush did not seem the kind of extrovert personality naturally suited to such a move –– there was an inevitability about the best British players leaving for the continent during the 1980s. In 1984 Rush had been lured by the lira on offer by Napoli — who offered Rush a £1m signing-on fee, aside from his wages, and were prepared to pay Liverpool £4.5m — but no deal was struck. However, with the Reds excluded from European competition, the club could not hang onto its prized asset. Dalglish, still a relative rookie, had to deal with something particularly rare: Liverpool as a selling club. He wanted Rush to stay, and told him that while the club were happy to cash in if he was set on a move, they were equally happy to retain his services. He also told Rush that the club wouldn’t object if he wanted to join Juventus, who had offered £3.2m, instead of Barcelona, who had bid £4.3m. Rush preferred Italy, which was seen as the world’s best league, and turned his back on a country that would have more suited his style of play, and a club that had an English manager in Terry Venables, as well as a friend and compatriot, Mark Hughes, already in the team. It also meant that Dalglish didn’t have as much money to reinvest in the team — but of course, by choosing a tough, defensive league, it ultimately made Rush returning to Liverpool more inevitable.

All the same, the money Juventus paid was enough to help Dalglish rebuild his side. His view to the club’s finances was simple: “The people who come to watch us play, who love the team and regard it as part of their lives, would never appreciate Liverpool having a huge balance in the bank. They want every asset we possess to be wearing a red shirt and that’s what I want, too.”

Rush spent what was meant to be his swan-song season at Liverpool scoring goals in his customary fashion — notching 40 times — but it was a trophy-free year, with Everton crowned champions. With weird timing, the Reds also finally lost a game in which Rush had scored: the 1987 League Cup Final against Arsenal breaking the seven-year run, as the Gunners came back from a goal down to seal a 2-1 victory. The loss of the most potent striker the English game had seen for decades was a big psychological blow, but it was quickly offset by Dalglish’s canny reinvestment of the fee. (Compare, for example, how Gérard Houllier wasted the money received for Robbie Fowler 14 years later.) Rush certainly wasn’t missed. Even so, he made a welcome return for an extended encore 12 months later, having struggled to adapt to Italy both on and off the pitch.

With Rush gone, the manager himself more-or-less retired, and a number of injuries and retirements, Dalglish had to build a new Liverpool team — and he did so in some style. Not only did he match the domestic feats of the past, he did so with a more flamboyant style. The 1987/88 side didn’t have as many tough characters and pure fire-and-blood winners as some of the sides fielded by Shankly, Paisley and Fagan, but it had some supreme individual ability and a quite breathtaking understanding. And all this was achieved with Lawrenson, the club’s most mobile defender, on crutches after a failed comeback attempt and, before the season was out, moving into management at Oxford United.

Another strong point was that Dalglish wasn’t afraid of players confronting him, having the strength of character to discuss why a certain decision had been made. Ronnie Whelan went to the see the boss, unhappy at being left out of the 1988 FA Cup Final, and later said: “Kenny doesn’t mind if you argue with him. But you can argue until the cows come home and you’ll never win.” Like a referee, a manager is unlikely to change his mind, but it takes a special skill to placate a disgruntled player and have him walk out of the office feeling that he is an important part of the set-up.

Weaknesses

While it was perfectly human of Dalglish to succumb to stress –– and, given that there were some exceptional extenuating circumstances, it might seem churlish to describe doing so as a weakness –– but ultimately he couldn’t cope, and that has to be recognised. Football managers deal with the weight of expectations of thousands, and in Liverpool’s case, millions of fans. There can be no doubting that it’s an incredibly difficult job; those who survive in the management game are built of different stuff when it comes to handling the unique kinds of pressure. Many managers work very long days, and simply cannot switch off from their job. Thought processes become obsessions. Hair quickly turns grey.

Dalglish’s tenure began as it would end — under great pressure and scrutiny. But initially he coped admirably. His first game, against Arsenal at Anfield, was played in front of the world’s media as all eyes turned to the club after the death of 39 Juventus supporters. The pressure would ramp up over the years, not least after great success in his inaugural campaign; increasing already stellar expectations. Then there was the sublime football of 1987/88, which was impossible to maintain. The old Liverpool way would no longer be as acceptable — grinding out results would be frowned upon after the élan of that vintage season.

By the end, he was desperate to escape the goldfish bowl. “In the past I would make the decision, usually more right than wrong and move on without thinking. Now I agonised over everything,” Dalglish explained. “The biggest problem was the pressure I was putting myself under in my desire to be successful.” He was experiencing headaches, and a rash had covered his body, even spreading onto his face. Almost daily a doctor visited Anfield to give him injections. Meanwhile, at home he was edgy and irritable, and constantly barracking his children; something he found incredibly upsetting. Having been pretty much teetotal, he began drinking wine in order to be more relaxed around his family. He was not in a good way, physically and psychologically.

A breaking point had to come, and on February 21st 1991, sitting ashen-faced alongside Noel White, he publicly announced his resignation. “I just can’t take it any more. I’m tired. The pressure is incredible. I can cope during the week but on match days I feel my head is exploding.” He claims he’d reached the decision before the most recent match, but clearly that tipped him over the edge; it’s one thing deciding to do something, another entirely to go through with it. That game was the 4-4 FA Cup draw with Everton — a match which had seen the Reds throw away the lead no less than four times, the third of which was in the dying moments of normal time, and the fourth at the end of extra-time. Originally, Dalglish had thought about resigning at the end of the 1989/90 season. He had originally told his wife Marina that he could only see himself in the job for five years, and as that milestone approached he was holding off signing a new contract. But he fought off his doubts and kept going. Without such a horrible game (from a management perspective) to endure, maybe he would have soldiered on yet longer, but it seems unlikely that the pressure would have abated. While Dalglish said that he knew beforehand that the match would be his last, there was an incident in the game that reinforced his belief. Sitting alongside Ronnie Moran with the Reds leading 4-3, Dalglish wanted to move Molby back to sweeper, to contain Tony Cottee, who was proving a handful. Moran suggested holding fire, and Dalglish acquiesced — but more out of a sense of indecision than agreement. When it came to making decisions, the old certainty had been replaced by doubts, and he felt weak-willed. Cottee equalised yet again, to make it 4-4, and Dalglish later noted that “the hesitation confirmed I was right to quit”.

It wasn’t just Dalglish wilting under the pressure at the time. Club captain Alan Hansen was also feeling the strain. “It makes me laugh when people talk about how confident I seemed on a football field because the reality is quite different. I suffered badly from pre-match nerves, and found it increasingly difficult to cope with the pressures of playing for a club like Liverpool.” It had reached the point where nothing short of total success was expected, and even the fans had become blasé about the accumulation of silverware.

In terms of the football Liverpool played, at its peak the team resembled Dalglish the player: stylish, thoughtful and committed. But as time passed, as well as being defensive to the media, the manager’s team selections were also growing increasingly cautious. The flair started to ebb out of Liverpool’s game, and defenders were increasingly lining up in midfield. Was the desire to hold on, to protect, a legacy of the loss of life at Hillsborough, or just another example of a manager trying to minimise the stress by reducing the risks?

Dalglish’s reasons for resigning were widely mocked in the media. Surely pressure is the preserve of the unemployed or the struggling nurse, and not that of a very wealthy man involved in sport, it was argued. While such observations are true to a degree, the manager of Liverpool Football Club carries the escapist hopes of the unemployed, the struggling nurse, and all manner of different people in society. He affects the mood of an entire city and increasingly, in this modern football age, millions of other tiny enclaves all over the world. It’s a big burden to carry, as is being responsible for the livelihood of those the club employs. Dalglish had bonded even more closely with the fans following Hillsborough — they had become more personal to him, not just faces in a bustling crowd, but real people whose lives often revolved around the club — and he did not want to let them down. While Shankly’s famous words were always meant to be tongue-in-cheek — football is of course not more important than life and death — it summed up the often illogical importance that people place on following their team. Football may not be more important than life or death, but it does add an incredible amount of value to the lives of those who pin their weekly hopes around a successful result. While Hillsborough, with the loss of 96 lives, including young boys and girls, put into perspective the relative irrelevance of winning or losing, paradoxically it also served to highlight the incredible importance of the club to its community.

And that’s before the pressure a perfectionist, a winner, like Dalglish puts on himself. Football is not like golf, snooker, darts or tennis, where the athlete carries his own hopes. Team sports bring an added responsibility, as seen in how golfers wilt when it comes time to perform as a collective in the Ryder Cup.

Despite his decision, Dalglish harboured hopes of returning later that year. “If Liverpool had waited until the summer, and then asked me to go back as manager,” he explained, “I would have gone back”. But by April Graeme Souness had been appointed manager. The board had asked Dalglish repeatedly to reconsider his decision when he tendered his resignation, and even suggested that he take a break until the summer and return for the next season. But no, he was adamant that he was going that day, and going for good. So it was no surprise that the club moved on and began to look elsewhere.

Historical Context — Strength of Rivals and League

In the mid-to-late ‘80 — still a time when a number of teams felt they had a realistic chance of winning the title — Arsenal and Everton provided Liverpool’s main opposition. George Graham’s Gunners perhaps borrowed some of the methods of Shankly’s Liverpool — not always the most aesthetically pleasing side in the country, but often the most determined and gritty. Arsenal had few of the exceptional individual talents that Shankly could call on, but they had a relentless strength and an obdurate defence.

Aston Villa provided the main threat in 1989/90. Perhaps it’s indicative of the weakness of the league at that time that their two strikers were Ian Olney and Ian Ormondroyd. The pair scored a rather pathetic 22 league goals in their 144 games for Villa, and were not good enough to sustain careers in the top flight. David Platt’s goals from midfield were the main threat, but this was not in any way, shape or form a great team. The exile from European football was taking its toll, and soon Platt would be joining the exodus of top British talent that had already diminished the quality of the top-flight; Platt moved to Italy for £5.5m, but by contrast, the record fee paid by an English club was just over half that amount. While it was proving hard for any club to lure top-quality foreign stars to England, the fact that Liverpool were thinking of bidding on Sunderland’s Marco Gabbiadini and were trailing QPR’s Roy Wegerle shows the dearth of available talent. So while the league had grown weak, there was also precious little talent to mine, as well as the lack of resources to compete with Italy and Spain. Without European football, it became harder to entice top players to the club.

As such, it’s impossible to say that in the ‘80s, or indeed the preceding decades, it was easier or harder to manage than in the current day, where the best players from any part of the world can be lured to the entire Premiership. Now there’s almost limitless choice. (But of course, that also makes scouting more complicated, given how far afield the search has expanded.) What is true is that, relative to their rivals, Liverpool were able to spend bigger in the late ‘80s than was possible 20 years later.

Manchester United were in a bit of a sorry state throughout the bulk of Dalglish’s tenure, with the exception of one year when they finished 2nd. In 1987/88, as Liverpool blitzed their way to the title, United finished as runners-up with 81 points, perhaps indicative of the massive improvements they’d go on to make at the start of the next decade. Alex Ferguson’s previous campaign — his first — had been fairly miserable, with United finishing 11th, but things would get much worse before they got decisively better. History now tells us that many of the elements were in place for United to topple Liverpool by 1989, but they would finish 11th again, and then 13th, five points above the relegation zone, before the long-term improvements would take hold. In Dalglish’s final season United, fresh from winning the FA Cup, rose to 6th in the league and won the UEFA Cup-Winners’ Cup. Their time was about to come, aided by Liverpool’s demise.

Bête Noire

Howard Kendall at Everton was almost certainly the man whose success vexed Dalglish the most in the early part of his tenure. Dalglish wrested the title off Kendall in his first season, but a year later the Everton manager was back, to land the crown. But the threat of Kendall was seen off for good a year later. As such, George Graham probably dented Dalglish’s hopes more than any other rival. It started with the League Cup Final of 1987, and culminated most famously at Anfield on May 26th 1989. Graham’s Arsenal would also win the title in 1991, with their obstinacy contributing to the pressure Dalglish found himself under in his swan song season.

Pedigree/Previous Experience

Like Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan, Dalglish had no prior first-team management experience in the football league. However, at least his two illustrious predecessors had spent many years in the game assisting managers, as well as spending a number of years overseeing the reserves, while Fagan had managed at non-league level. Dalglish was a complete rookie, but he was clever enough to surround himself with people who knew the ropes, with Paisley on hand to offer assistance. In the end, he didn’t seek out Paisley’s advice that much. According to Ian Ross, the former Liverpool utility man, Paisley hadn’t been consulted once during the first six months of the arrangement. Dalglish had learned a lot from Paisley, and had requested his knowledge be on tap, but when it came to it, Dalglish was proving to be very much his own man.

Subsequent Career

At Blackburn Rovers, bankrolled by steel magnate Jack Walker, Dalglish became only the third manager to lift the Championship with two different clubs — a feat previously achieved by Herbert Chapman and Brian Clough. Despite losing 2-1 at Anfield on the final day of the 1994/95 season, the Lancashire club were crowned champions when Manchester United failed to beat West Ham. It was just like old times, with Dalglish winning the title in front of the Kop and United crestfallen. Having achieved his aim, he surprised everyone by immediately moving to an ‘upstairs’ role as Director of Football; Blackburn promptly imploded.

Next he moved to Newcastle, but his football was seen by fans as too defensive following on from Kevin Keegan’s gung-ho attacking. When Dalglish took over, in January 1997, Newcastle were 4th in the table; they eventually finished 2nd, and went into the Champions League at Liverpool’s expense, where they beat Barcelona 3-2. Proving his judgement in the transfer market was as strong as it had been in his early days at Liverpool and Blackburn, Dalglish signed crowd favourites Nolberto Solano, Gary Speed and Shay Given, as well as future Liverpool star Dietmar Hamann. The manager also took the club to an FA Cup Final in 1998 — a rarity on Tyneside — but the Geordies finished 13th in the Premiership, with just 44 points. Two games into the following season, both of which were drawn, Dalglish was sacked. He then experienced a brief spell as Director of Football at his alma mater, but his partnership with rookie John Barnes saw Celtic struggle. With Barnes sacked mid-season, Dalglish saw out the campaign as caretaker, during which time the Bhoys beat Aberdeen 2-0 to win the Scottish League Cup. Shortly after, he was replaced by Martin O’Neill, and hasn’t managed since.

Defining Moment

Unquestionably, the defining moment of Dalglish’s reign came on April 15th 1989. Until then it had been a relatively straightforward job –– it was just about managing a football team, albeit one with lofty expectations and intense pressure. But that fateful day at Hillsborough changed everything. Understandably, something fundamentally altered within Dalglish. For a while the job became about being a grief counsellor whilst also carrying his own sadness. Football was secondary. Indeed, it didn’t even rank that highly –– there was the aftermath of a disaster, and that was it. The game itself was the last thing on everyone’s mind. Liverpool was a community in mourning.

The toll it took on the club might not have been instantly obvious. Once the football eventually resumed, the Reds came back strong to win a number of consecutive league games, only falling at the final hurdle against Arsenal (to Michael Thomas’ last-gasp title-winner, in the 3,420th and final minute of the season), and then landed the FA Cup in Dalglish’s second all-Merseyside final, in which Ian Rush repeated his double from three years earlier. The following year the Reds won their 18th league title, but it was after that point that the cracks began to appear for the manager. The end came in February 1991. Dalglish severed all ties with the club 14 years after first arriving.

Crowning Glory

Clearly, Dalglish took English football to a new level in 1987/88. Liverpool finished the season with 90 points, equalling Everton’s record, despite playing two fewer games. The Reds won 26 games and lost just two, scoring 87 goals and conceding only 24. The success was achieved with Dalglish’s 1987 signings weighing in heavily with goals. Aldridge scored 29, Barnes 18, Beardsley 17, and Houghton added a further seven — an incredible 71 goals from the new boys. To underline how much this was his team and not the work of his predecessors, Steve McMahon, Dalglish’s first signing, added an impressive nine more goals from centre-midfield.

The stats do some justice to the brilliance of that season, but cannot tell the whole story: one of stunning interplay and darting movements off the ball; of defenders attacking and players interchanging across the pitch. The brilliance culminated in a 5-0 thrashing of 2nd-placed Nottingham Forest in April 1988. Michel Platini, European Footballer of the Year for three years running earlier that decade, had already described the 2-0 victory over Arsenal as a “European display”. Now former England winger Tom Finney was saying that the football in the 5-0 victory over Nottingham Forest was the best he’d ever witnessed; even Brazil couldn’t play so well at that pace, he said.

Legacy

Dalglish’s legacy is the one slightly murky aspect of his spell as Liverpool manager. The squad he left for Graeme Souness was full of players who were past their best, some recent signings who were patently not good enough, and a smattering of youngsters who were not yet ready for the first team. If he hadn’t resigned, Dalglish would have had a hell of a job on his hands sorting out the wheat from the chaff.

But while it would not reap rewards in time to benefit him, Dalglish’s overhauling of the youth system was perhaps his greatest legacy. A club can only discover the blossoming talent that already exists in the area — or at least it could at the time, before permission was granted to cast a net further afield. Attracting exceptional kids like Steve McManaman and Robbie Fowler to the club was not a formality; both were Evertonians, for starters. The same was true of Michael Owen and Jamie Carragher a few years later. Before Steve Heighway took charge, very few players were making the grade through the Liverpool youth ranks; in the next 12 years, the club produced its best clutch of local talent. Perhaps it was all merely coincidental — the result of the cyclical nature of the emergence of home-grown players, and the random act of a future star just happening to be born in one part of the country and not another. Despite Heighway continuing to work in the same way after 1998, when Steven Gerrard broke through, only fairly mediocre players, with the exception of Wayne Rooney, emerged on Merseyside.

Transfers In

It’s fair to separate Dalglish’s signings into two categories: the great (1985-1988) and the not-so-great (1988-1991). It is not an exact categorisation; there are some exceptions. But on the whole, the purchases the Scot made in his first three years would wipe the floor in a six-a-side game with those made afterwards.

Dalglish’s first signing, in 1985, set the tone for those initial impressive major acquisitions. Former Evertonian Steve McMahon was snapped up from Aston Villa for £350,000, and while he never quite reached Souness’ imperious heights, he did go a long way to replacing the mixture of grit, good distribution and an eye for goal. The Scouser left the club six years later with 50 goals from 276 games, at a rate of one goal every 5.5 matches –– impressive for a non-penalty taker.

In his first couple of years, Dalglish made a number of lower key, inexpensive signings; the kind of gambles that most managers make when bolstering a squad, and which inevitably end up as a very mixed bag. Mike Hooper was an able reserve goalkeeper, bought from Wrexham for £40,000 in October 1985 at the age of 21. Hooper lasted eight years at the club, eventually racking up 72 appearances, mostly at a time when Graeme Souness was trying to decide between the Bristolian, a young and erratic David James and an ageing Bruce Grobbelaar. Never good enough to stand a realistic hope of being the Reds’ long-term regular custodian, Hooper was eventually sold to Newcastle in 1993 for 13 times what Dalglish had paid, making the signing a good bit of business.

Liverpool paid Sunderland £250,000 for Barry Venison’s services on July 31st 1986 –– a decent but unspectacular full-back. Venison would go on to play 110 league games for the club, and helped in winning the league titles of 1988 and 1990. As the defence around him deteriorated, with class replaced largely by mediocrity, he was more exposed; had he been fortunate enough to play alongside prime-years Hansen and Lawrenson, he might have flourished, but instead he stagnated and moved to Newcastle in 1992, being reborn as a holding midfielder and even managing to win two England caps. Another full-back, Steve Staunton, was spotted as a 17-year-old playing in Ireland for his home club of Dundalk, and was signed in September 1986 for a measly £20,000. The young left-back did well after making his debut in 1988, and even scored a hat-trick in a League Cup match –– as a substitute! But he was sold three years later, by Souness, for 55 times what the club had paid; some mark-up on a canny bit of business by Dalglish.

Striker Alan Irvine arrived in November 1986 from Falkirk, costing £75,000, but he never managed to settle. John Durnin, who arrived from Waterloo Dock in 1983, became a professional in March 1986, but never made the grade, registering just one start and one further substitute appearance. Mike Marsh, another striker, was signed in August 1987 from Kirkby Town, making his debut two years later as a 19-year-old against Charlton Athletic. Neither tall nor quick, he was shunted around the pitch by Souness, under whom he briefly flourished. Marsh excelled in midfield against Genoa in the UEFA Cup in 1992, having scored a crucial goal from right-back against Auxerre in the winter in a thrilling, and necessary, 3-0 win. But he was never able to translate his excellent skill and technique, which won him admirers in training, into consistent top-level success.

Getting back to major signings, Dalglish’s judgement in 1987 proved peerless –– almost certainly the club’s best-ever calendar year when it came to buying a number of players, edging out 1977 on account of the extra transfers involved. Inward-bound transfers in ‘87, funded largely through the pre-agreed sale of Ian Rush to Juventus, saw Dalglish create what could finally be called his team. By the autumn of 1987, with Rush and Souness overseas, Lawrenson injured, and Alan Kennedy and Phil Neal long gone, only Alan Hansen, Steve Nicol, Ronnie Whelan and Bruce Grobbelaar remained as key men from Joe Fagan’s treble-winning side of 1984. And, of course, Dalglish himself had unofficially hung up his boots. Craig Johnston was also still in the squad, but became increasingly peripheral, and retired in 1988. Meanwhile, Fagan signings Jan Molby, John Wark and Paul Walsh were also mostly out of the first-team frame.

Dalglish started the year as he meant to go on: John Aldridge arrived in January for £750,000, with Rush’s departure already predetermined for six months’ time. The Scouser was a deceptive talent. He didn’t look much of a footballer in terms of grace and style, and wasn’t the quickest or tallest. He also had no discernible skill. But within the box he was lethal, and particularly good in the air. The return of Ian Rush a year later meant that Aldridge, after one more season, was surplus to requirements, and sold for £1m to Real Sociedad in 1989. He became the first non-Basque player ever signed by Sociedad, and was a big hit in San Sebastián, scoring 40 goals in just 63 appearances. Keeping Aldridge at Anfield would have meant another player in his 30s inherited by Souness, but the striker continued to bag goals at a prolific rate for years to come; he scored a staggering 138 times beyond the age of 33 at Tranmere, albeit in a division below the top flight, and his final career tally was an unbelievable 476 goals. Unlike Ian Rush, he was a penalty taker, and scored 17 (27% of his overall total) from the spot for the Reds; his only miss was in the 1988 FA Cup Final, and costly it proved. After 50 league goals for the Reds in 83 games, the club then made a profit on his sale. You can’t ask for more from any signing than to score an abundance of goals that help win major honours, and to then make the club a profit further down the line.

Chelsea midfielder Nigel Spackman joined Liverpool in February for £400,000, and while he wasn’t a resounding success, he proved much more than just a squad player, making 50 starts and 13 substitute appearances in his 24 months at the club. Solid, unfussy and unhurried, some of his best football came as the holding midfielder in Dalglish’s free-flowing team of ‘87/88; the ‘water carrier’ to keep things ticking over as the more skilful individuals wreaked havoc.

Peter Beardsley, a little gem of a player, arrived in July for £1.9m from Newcastle, although it took him a few months to settle. Part of Beardsley’s initial struggle was that he was simply overshadowed by Aldridge, who couldn’t stop scoring, and Barnes, who was in sensational form. Perhaps the little Geordie was also suffering under the burden of being the most expensive footballer in Britain at the time. But by the start of 1988 ‘Beardo’ really began to come into his own. He was a real twinkle-toes-type player, often skipping between two hefty defenders after his trademark shimmy –– kind of like a dog cocking his leg whilst performing the Riverdance, he lifted his foot high and to the side, before lowering it to jink one way or the other.

Ray Houghton, purchased from Oxford in October for £825,000, was the final piece of the Dream Team jigsaw, and rounded off a great year in the transfer market. He slipped seamlessly into a side that went on to record a 29-game unbeaten start to the league season and progress to the FA Cup Final. Mobile, tenacious, busy, and not without skill, he was a hugely effective player who added a new dimension to the Reds’ play, particularly with the way he switched wings with John Barnes in the fluid system. He scored 38 goals in 202 games for the Reds before he was sold to Aston Villa for £900,000 at the age of 30.

Ian Rush returned for £2.8m in 1988, just a year after departing for Italy. Never able to recapture the prolific form of his younger years, and with a lot to live up to as a returning legend, he was still a welcome addition to the team; had an unknown player achieved what he did between 1988 and 1996, he would have been considered a big success. With Aldridge gone, Rush came to the fore in 1989/90, scoring 26 goals in a season that saw the Reds land the title. In his second spell, Rush managed 90 league goals in 245 games –– a fine tally, but nowhere near as impressive as his first seven years, during which scored 139 in 224 matches; of course, Rush also scored a staggering 117 cup goals for the club in his two spells. The diminished return was perhaps also due to an altered role once Robbie Fowler appeared on the scene in 1993, as well as the fact that the man who created most of Rush’s goals in his first spell was now the team’s manager. And of course, it encompassed the tail end of the Welshman’s career, when the intelligence was getting sharper but the the trademark pace was a thing of the past. When any player arrives at a club, one thing that is hard to judge is the effect he has on those around him –– how much he teaches them, directly or indirectly, and any influence on their attitude. In Fowler’s case, he clearly owed a debt of gratitude to Rush, and while the teenage heir to the no.9 shirt was always destined for great things, the presence of the elder statesman undoubtedly helped him reach his potential.

Making far less headline news, centre-back Nicky Tanner, signed for £30,000 from Bristol Rovers in July 1988, managed 50 games for the Reds, mostly under Graeme Souness. Not the most graceful, Tanner was solid, both physically and in his play. Another defender, David Burrows, arrived in October 1988 from West Bromich Albion, the fee set at £550,000. It was money well spent –– the value about right –– with Burrows featuring in the 1990 title-winning side, and leaving for West Ham in 1993 for a profit after almost 200 appearances for the Reds.

Glenn Hysen arrived in 1989, when the high-profile signings weren’t working out so well for Dalglish. Liverpool beat off competition from Manchester United, for whom the centre-back was about to sign from Italian side Fiorentina for £650,000. The silver-haired Swede was part of the league-winning side at Anfield in his first campaign, and often excelled, but never quite reached the heights Liverpool fans were accustomed to over the course of his career. It was a time when Kopites were used to Mark Lawrenson, who’d retired less than two years earlier, and Alan Hansen, who was entering his final season; as such, almost anyone would suffer by comparison. Hysen seemed to struggle more than most when it came to the difficulties the team experienced under Graeme Souness, although by that stage he was in his early 30s; as such, he only lasted until 1992, when he returned to Sweden. As it was, it would be a whole decade before Liverpool signed another totally successful centre-back, in the form of fellow Scandinavian Sami Hyypia.

Steve Harkness was also picked up for £75,000 in the summer of 1989, at the age of 17. Harkness made his debut two years later, at QPR, and served the club in a steady if unspectacular manner under both Graeme Souness and Roy Evans, and briefly under Gérard Houllier, who experimented with him as the holding midfielder. In his full decade at Liverpool Harkness managed to play 139 times, and is probably best remembered as one of Evans’ three centre-backs in the 3-5-2 formation.

The biggest instant impact of any Dalglish signing was probably made by Ronny Rosenthal; John Barnes captured the imagination like no other new player arriving at Anfield, but not even he could affect the destination of the league title in his first few appearances. The Israeli’s seven goals in eight games when on loan from Standard Liege helped the Reds secure the 1990 championship, but he failed to build on his surprise success once a permanent £1m deal was secured in the June of that year. Quick, strong and direct, Rosenthal was in truth a graceless bustler with a big heart who often bulldozed his way through defences and thumped shots at goal. An impact signing, ‘Rocket Ronny’ was also an impact player, making 57 substitute appearances, some 15 more than he gained through starts. In his next three-and-a-half years at the club, Rosenthal only managed to double his total goals tally.

Attacking midfielder Don Hutchison was brought to the club from Hartlepool in November 1990 for £175,000, after Dalglish and his scouts saw the 18-year-old’s potential in a video they received from the selling club’s chairman, who was seeking to cash in on his team’s League Cup escapades against Spurs. Hutchison made his debut in 1992, under Graeme Souness. Two years later Roy Evans opted to sell the player for a tidy profit, making him another successful Dalglish purchase in monetary terms, even if the Scottish international didn’t really fulfil his potential at Anfield. Hutchison arrived a couple of months after the Reds had signed 21-year-old Irish striker Tony Cousins from Dundalk for £70,000. Cousins lasted two and a half years at Anfield but never played a game before being released.

If Ronny Rosenthal provided the biggest impact, David Speedie, having just turned 31 when he arrived for £650,000 in February 1991, was Dalglish’s most left-field signing. Every manager seems to make at least one; the older player who’s been around the block, and who has ability, but whose signing comes totally out of the blue. Gary McAllister was one such player signed by Gérard Houllier, while Rafa Benítez shocked the football world by bringing back Robbie Fowler five years after he’d been sold. Six goals in 12 games from Speedie, including two against Everton and one against Manchester United, seemed the start of a promising late-career stint at Anfield but Graeme Souness had other ideas. Speedie dropped down a division, to upcoming Blackburn Rovers, and by October was being managed by Dalglish once again; in 36 games en route to promotion, Speedie netted 23 times, only to be sold as soon as Rovers reached the newly-formed Premiership.

Having covered ‘impact’ and ‘surprise’, Jimmy Carter was Dalglish’s most baffling signing; so ineffectual was he that the former US President of the same name, at the age of 66, might have done as good a job. What’s more bizarre is that Liverpool managed to offload the ex-Millwall winger to their closest rivals at the time –– George Graham’s Arsenal –– where he also flopped. The best thing that can be said about the signing of Carter is that the Reds got most of their money back.

Dalglish at least redeemed himself with his final signing: Jamie Redknapp, bought from Bournemouth for £350,000. Never destined to be one of the true greats like Souness and Gerrard, he was however a fine natural footballer with an ability to pass long and shoot from distance. As such, he was a very good Premiership player for a number of years and proved excellent value for money. Redknapp racked up 308 appearances for the club in just over a decade, a tally that, but for a series of injuries in his later years, would have been far greater. He scored 41 goals, before moving to Spurs in 2002.

Key: Quality 0-10; pg = 0.01 per game; IN = fee paid relative to transfer record, 5 being 50%, 10 being 100%, figure expressed as negative, with weighting added to players over 28; OUT = fee player sold for/current transfer value/longevity in first-team, expressed as positive; FGV = future game value; VALUE = Value For Money; Ap = Appearances; Details lists cost and year, plus sale or retirement information. Inexpensive and youth signings who never featured for first team and reserve keepers excluded. * Club record fee ** English record fee

Transfer Masterstroke

John Barnes, signed for £900,000, was undoubtedly Dalglish’s masterstroke. While Steve McMahon would prove to be the best signing in terms of Value for Money, Barnes was the player who made the difference; the player who took the team to the next level.

The fee wasn’t cheap by 1987 terms (60% of the record), but was still less than half what the club would pay for Beardsley later that same summer. There were a lot of doubts about Barnes before his arrival; he was clearly talented, but could he hack it at a big club? The answer was an emphatic ‘yes’. It also hadn’t helped that he’d been holding out for a move to Italy. Arsenal had withdrawn their offer in a huff as a result, and Barnes almost had no alternative but to sign on the dotted line with Liverpool. With games rarely televised, and Anfield closed for repairs due to a collapsed sewer beneath the Kop, the buzz about Barnes had grown through his initial away performances. The home game with early league-leaders QPR, televised as the main highlights in the evening, showed what the fuss was about. The Reds won 4-0, demolishing QPR, who imploded like the Kop sewer. Barnes scored two goals –– one brilliant, the other almost off the scale. The first saw him exchange passes with Ronnie Whelan before curling a shot into the top corner past a young David Seaman (who that day perfected his look of dejection, as later made famous by the efforts of Nayim and Ronaldinho). But Barnes’ second goal was the stuff of genius. He won the ball on the halfway line, and strode purposely upfield. Faced with three defenders, including England internationals Terry Fenwick and Paul Parker, he jinked to his left and then, with balletic grace and a seemingly impossible shift of his weight from one side to the other, glided to his right. The finish itself was made to look simple, with the ball slid under the advancing Seaman, but again, it perhaps showed why Barnes was so devastating. Other skilful players might have looked to do a little extra, and, with a rush of adrenaline, showboated the finish with a dink or yet one more dummy or shimmy. The beauty of Barnes’ skill was that he never did the unnecessary, never wasted time with the superfluous. It was a defining moment in the season; it scared the life out of every top division footballer watching the TV that night, and a new Liverpool side had officially come of age.

Having terrorised full-backs on the wings, Barnes would later be asked by Dalglish to use his talents to take centre-backs to task. Excellent in the air, his skill and strength served him well as a centre-forward, and in 1989/90 he scored 28 goals, making him the country’s top scorer, just edging out Ian Rush on the last day of the season. He had an ability, if you will, ‘to hold and give but do it at the right time’. When an Achilles tendon injury robbed Barnes of his pace, he was later reborn as a central midfielder under Roy Evans, just to outline how excellent technical ability can make a player adaptable. Barnes’ time at Liverpool came to a close a decade after arriving. He played 407 times for the club and scored 108 goals.

Expensive Folly

Most of Dalglish’s major signings worked to perfection: McMahon, Aldridge, Beardsley, Houghton, Barnes and the returning Rush (although at almost £3m he wasn’t great Value for Money). But the £1m spent on Ronny Rosenthal — 37% of the English transfer record — was probably the greatest waste. Of course, after such an impressive loan period, when the Israeli had been so sensational in helping land the 1990 title, it would have been a brave man who didn’t stump up the cash, but once a permanent move was finalised he proved to be somewhat of a flash in the pan. In many ways it was the most inspired loan move in the history of the club, but one of the least successful transfers.

Jimmy Carter, at £800,000, was not cheap either. Dalglish felt the player had a bit of everything — pace, technique and the ability to cross the ball — but that his problems were of a mental nature, in dealing with the expectations at such a big club. Dalglish, having worked closely with the player, will know that better than most. But when it came to match-days, the fans saw a player who looked patently out of his depth.

One Who Got Away

In 1985 Liverpool had hoped to sign Paul Allen, the 23-year-old West Ham midfielder who, in 1980, became the youngest-ever FA Cup finalist. Talks were held, but Allen opted to stay in London, with Spurs.

Michael Laudrup, the Danish maestro who had been at Juventus since 1983 (although loaned out to Lazio until after Juve beat Liverpool in the 1985 European Cup Final), was once again linked with a move to Liverpool. In 1987, with Ian Rush due to join him in Italy, the Dane said “I will stay with Juventus until 1989, and then I think I’ll join Liverpool”. But instead he ended up at Barcelona, where he won four La Liga titles in a row, and then moved to Real Madrid, to instantly win a fifth. In 1999 he was voted the Best Foreign Player in Spanish football over the previous 25-year period, to highlight just what a talent the Reds had missed out on.

Budget — Historical Context

Having spent big in the mid-to-late ‘70s, Everton would only find success once they reverted to the products of their youth system, supplemented by a number of cheap young players bought from unfashionable clubs. The twelve men involved in the 1986 FA Cup Final defeat to Liverpool — most of whom had won Everton their league first title in 15 years the previous season — had an average cost of just 13.6% of the English transfer record. Of that side (Bobby Mimms, Gary Stevens, Pat Van Den Hauwe, Kevin Ratcliffe, Derek Mountfield, Peter Reid, Trevor Steven, Gary Lineker, Graeme Sharp, Paul Bracewell, Kevin Sheedy, Adrian Heath), only Lineker and Heath cost over £500,000. While Liverpool were one of the few big clubs yet to spend a million, the average cost of their side — famous for not including one Englishman in the starting XI (Grobbelaar, Lawrenson, Beglin, Nicol, Whelan, Hansen, Dalglish, Johnston, Rush, Molby, MacDonald, and substitute McMahon) — was double that of their neighbours, at 28.7%.

Like Everton, Arsenal’s success under George Graham in the later part of the ‘80s was also largely down to their youth system. Tony Adams, David O’Leary, Paul Davis, David Rocastle, Michael Thomas, Niall Quinn, Paul Merson, Kevin Campbell and Martin Hayes were all home-grown talents who played for the Gunners during Dalglish’s time at Liverpool. Expensive marquee signings like Charlie Nicholas and Steve Williams gave way to a group of talented youngsters and, on the whole, bargain signings. David Seaman (£1.3 million, 1990), Andy Linighan (£1.25m, 1990) and Alan Smith (£850,000, 1987) were the exceptions, but otherwise Graham bought relatively cheaply: Nigel Winterburn (£350,000 in 1987), Lee Dixon (£400,000 in 1988), and Kevin Richardson (£200,000 1987) were three very successful examples, with the first two playing well over 1,000 games for the Gunners between them.

One club who were spending big at the time was Manchester United. Alex Ferguson had taken charge in 1986, and by 1989 he’d spent in excess of £13m on players, with precious little recouped through sales; by contrast, Liverpool’s gross spend in that period was almost exactly half, and that included the sale and repurchase of Ian Rush. As had Dalglish, Ferguson bought back the club’s star Welsh striker after an unhappy time abroad, although Mark Hughes had been sold by Ron Atkinson. The United team that won the 1990 FA Cup Final — the result that saved Ferguson’s job, after his third bottom-half league finish in four seasons — was formed from a number of expensive signings. Only Lee Martin, the unexpected hero in the replay, did not involve a fairly significant transfer fee, and only Bryan Robson was not a Ferguson purchase. The side — Jim Leighton, Paul Ince, Lee Martin, Steve Bruce, Mike Phelan, Gary Pallister, Bryan Robson, Neil Webb, Brian McClair, Mark Hughes and Danny Wallace — had an incredible average cost in excess of 50% of the English transfer record. Ferguson eventually dug himself out of a hole, but did so with a massively expensive average spend that, in relation to the English transfer record, was identical to the Chelsea side that Liverpool beat in the 2007 Champions League semi-final. Ferguson’s spending dropped dramatically over the next three years, but by then he had assembled the majority of the side that would go on to win the 1993 Premiership title, and end a 26-year wait to become champions; at which point he broke the English transfer record on Roy Keane.

Conclusion

Kenny Dalglish’s tenure ended as it started — in the wake of tragedy; his time in charge bookended by the deaths of 135 fans in failing stadia. As a manager he will be remembered for the beautiful football of 1987/88, and the double two years earlier. Three titles in five full seasons, plus two FA Cups, achieved with the best win-percentage of any Liverpool manager in modern history, highlights Dalglish’s quality. He bought brilliantly at first, while overhauling the youth system. But criticism of his later purchases, and the possibility that the sacking of Geoff Twentymen contributed, cannot be escaped.

How sad, though, that the manager’s greatest side could not test its mettle in Europe. The fact is that in 1987/88 Liverpool would only have been in the UEFA Cup anyway, but had they contested the European Cup they would have stood a good chance of winning it, with the moderate talents of PSV Eindhoven beating Benfica in the final. It would have been interesting to see how the Reds fared against the Rossinieri, with the great AC Milan of Gullit, Van Basten, Rijkaard, Baresi, Maldini, Donadoni and Costacurta winning the Italian league in 1988 and romping to the European title in 1989. But it wasn’t to be.

Not many outsanding players make great managers, but for a time Dalglish was certainly as adept in the dugout as he was on the pitch; a fact borne out by his league triumph with Blackburn in 1995, before his career tailed off. And as a man he will be remembered for the grace and dignity with which he conducted himself in testing times at Anfield. Few people have given more to the Liverpool cause, and Dalglish will forever be a club hero.