By Mihail Vladimirov

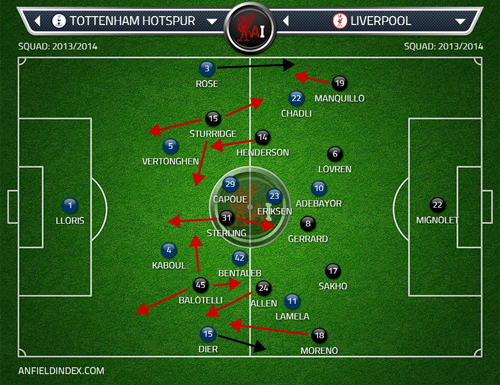

After having to rotate his squad for the Europa League qualifier on Thursday, Pochettino unsurprisingly opted to keep the same XI that thrashed QPR last week. The formation remained the same 4-2-1-3 with Lamela (right) and Chadli (left) flanking Eriksen in behind the lone striker Adebayor.

For Liverpool, Rodgers continued to vary his starting approach. For a third game in a row he started with a different formation. After using the 4-2-1-3 and the 4-1-2-3/4-3-2-1 in the last two games, now it was time for the manager to use the 4-diamond-2 formation. Additionally to the change in the formation, there were a few personnel changes. The injured Skrtel and Johnson were replaced by Sakho and Manquillo, while Coutinho, who has performed poorly up to now, was benched in favour of Balotelli, who was making his debut.

This was a hugely enjoyable clash between two of the most progressive managers in the division. Although it ended much more one-sided than initially anticipated – with Liverpool completely outplaying Spurs – the game offered plenty of fascinating aspects on the tactical front.

Liverpool’s supremely mature, if a bit risky, approach

Knowing Pochettino and based on how Spurs have played up to now under their new manager, it was logical to conclude the main threat for Liverpool would come in the face of the opposition’s midfield press in addition to the movement fluidity and constant interplay provided by their roaming front quartet. What impressed in Liverpool’s approach was that it was equally measured and risky but above all it was impressively mature in how the team simply got out and displayed the intelligence and composure to impose their own aggressive style without leaving the opposition’s strengths uncovered.

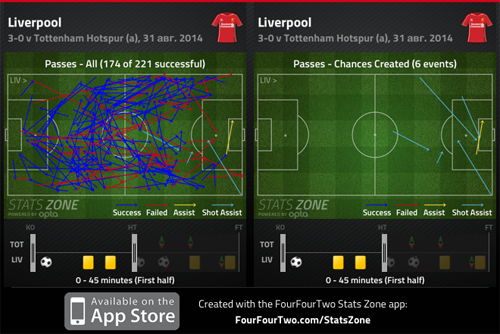

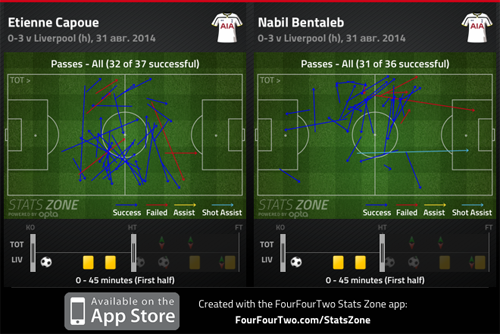

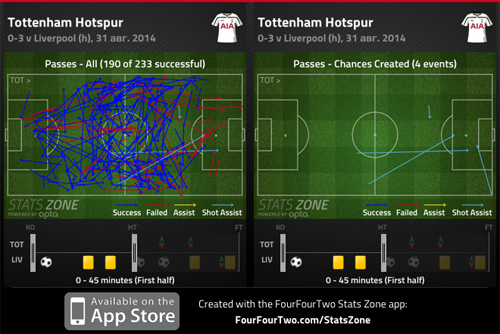

With both managers liking their team to be on the ball as much as possible, the first obvious tactical battle was going to be who would command the bigger share of possession. As both teams had the personnel to keep the ball and dictate the play from different zones and in different ways (the long passes of Gerrard and Capoue, the ball retention of Bentaleb and Allen, the incision provided by Spurs’ front 4 and Liverpool’s front three keenly helped by Henderson), the extension of this particular battle was how the teams would prevent each other getting time on the ball. The obvious solution was to see both teams fiercely pressing each other.

However, neither team opted to press aggressively deep in the opposition’s half, apart from sporadic individual attempts from the attacking players. But both teams kept very advanced defensive lines and put extra emphasis on closing down quickly in the midfield third. Plus, with the presence of both Sturridge and Balotelli up front, Liverpool indirectly further prevented their hosts being so aggressive with their pressing as to press from so high up the pitch. Obviously this was something anticipated by Rodgers, as it was notable how Spurs under Pochettino aren’t pressing deep in the final third as Pochettino’s Southampton often did.

With Liverpool expecting Tottenham to apply a press mainly in the midfield zone, the first thing the visitors had to deal with tactically was to prevent the home team doing exactly that. There were two main patterns prepared as actions against this.

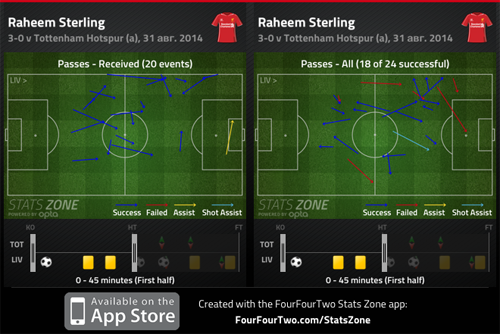

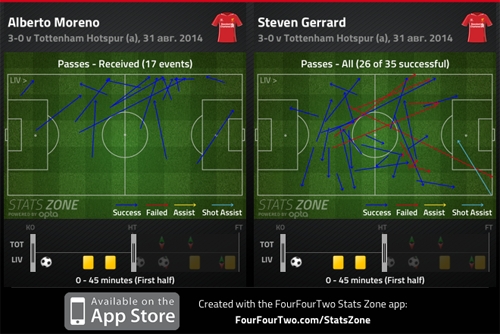

The first one was how exactly Liverpool’s diamond formation morphed during the build-up play. With Gerrard dropping near and often between the centre-backs (more on this later), the full-backs, the side midfielders and Sterling had key roles to perform in order to prevent Spurs’ midfielders having the upper hand in terms of numerical advantage, and therefore creating enough pressing angles in that zone. Often both Moreno and Manquillo pushed forward whenever Gerrard moved to the opposite direction, forcing back Spurs’ full-backs. Meanwhile Sterling was quick to drop back, often just beyond the central line, and offer himself as a receiver of the ball. This meant that Spurs’ only way to allocate enough pressing bodies in order to outnumber Liverpool in the midfield zone – to press them adequately and ensure they have higher chance to win the ball back – was to push at least one of Bentaleb or Capoue forward. But as it was, both players looked tentative and overly cautious with their positioning, presumably fearing to leave their centre-backs 2-v-2 with Balotelli and Sturridge.

All this meant that often the midfield battle would be 3-v-3 with Lamela, Eriksen and Chadli up against Allen, Henderson and Sterling. However, it was also clear that Spurs’ wide men looked rather unsure how to proceed with their exact pressing activities. At times they looked to half-heartedly try to close down Sakho and Lovren, meaning it was easy for Liverpool to quickly pass the ball to one of the three midfielders sitting free ahead of them. Other times they tried to move infield and occupy Allen and Henderson, only to then see Liverpool’s centre-backs passing to the full-backs as a way to play the ball out. Basically, Liverpool often had six players inside their own half against Spurs’ front quartet, which meant in any given moment there were enough completely unmarked players to quickly receive the ball and run forward with the ball.

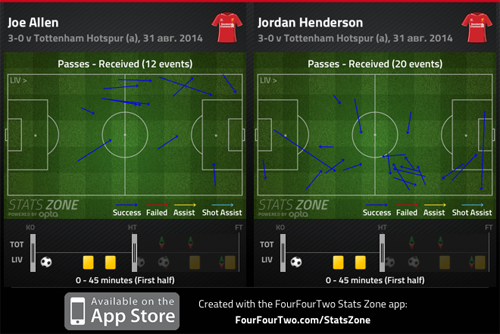

Still, it was clear that Liverpool had a preference as to how to play out the ball. Henderson and Allen especially rarely received the ball inside their half, as it looked they were mainly used as decoy players to confuse Spurs’ advanced pressers and ensure the team would have enough free bodies.

The main pattern involved the ball reaching either Sterling dropping back or one of the full-backs as if the team explicitly wanted to feed players who would be able to carry the ball forward at speed, and quickly get past any closing down opponents. There were several situations where one of Allen (mainly) or Henderson (rarer) was free to receive the ball, only for the team to continue recycling and wait extra seconds to find a way to get Moreno, Manquillo or Sterling on the ball instead. Perhaps it was Rodgers’ way to guard against his team being closed down and not risk Gerrard or Allen bringing the ball out, as they are vulnerable to concede possession when being quickly pressed.

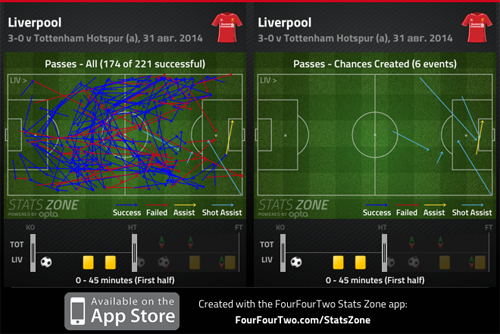

Right from the start the above pattern, including Sterling dropping back to pick up the ball and bring it forward, was evident. In the third minute Liverpool worked the ball well from the back down the left channel, involving Sterling getting back to pick up the ball then bring it forward to initiate a passing move including Allen, Moreno and Sturridge. With four players close to each other in that zone Liverpool overloaded Spurs and found it easy to create a very good attack. After a nice exchange of passes between these four players – at one time Gerrard joined too – the ball reached Sturridge, who was drifting to the flank to join the attacking move, who then crossed brilliantly for Balotelli on the far post. Unfortunately for the visitors, it was a case of Lloris pulling off a good save in addition to the Italian’s header being rather poorly placed.

Another example of Liverpool overloading Spurs in the midfield zone to first prevent being closed down then to quickly and purposefully play out the ball in attack came in the 12th minute; it was again Sterling initially coming back to pick up the ball, then bursting forward to get past both Capoue and Bentaleb before releasing Sturridge into a good shooting position.

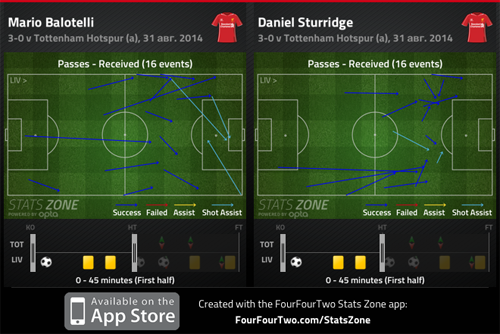

What’s more, it wasn’t only Sterling who was keen to drop back and assist his team during the early build-up play and prevent Spurs closing down in midfield. More often than not, one of the forwards would also drop deep, after initially positioning himself down the inside channels to cause uncertainty about who exactly should mark them – the full-backs or the centre-backs. That confusion often meant Spurs’ back four being poorly arranged and often leaving either Liverpool’s centre-forwards (if the centre-backs opted to stay put and the full-backs were on Moreno and Manquillo) or the full-backs (if Rose and Dier opted to came narrow and closer to the centre-backs in order to minimise the gap between them for Balotelli and Sturridge to potentially exploit) completely free to pick up the ball and initiate the attacking move. Not only did Balotelli and Sturridge both show exceptional work rate in attack to constantly be on the move, roam and rotate their position to work the whole width of the final third between themselves, but they showed great team ethic and defensive discipline to have one of them always coming deeper to assist the build-up play.

The situation in the 31st minute perfectly illustrates the above input from Liverpool’s forwards, in addition to the confusion across Spurs’ backline leading to certain defensive issues, namely poor understanding and strange positioning of their defenders. With Balotelli dropping back beyond the half-line, it should have been a case of either Dier or Bentaleb getting closer to him. Instead, the overall confusion led to poor cooperation, with Kaboul opting to rush forward and try to get tight on the Italian. In a matter of seconds, Balotelli spun around the defender and send a nice little through ball for Sterling moving into the vacated space from deep, who had been tracked back by Bentaleb as Vertonghen was sent in other direction by Sturridge’s movement. All of this forced Lloris to come out and sweep decisively, although his poor clearance put the ball back to Balotelli. Again, in what was a goal-scoring situation, the Italian’s finishing touch was inaccurate, as he put the ball way, way off target.

The second pattern illustrating how Liverpool were prepared to beat any incoming Spurs pressure in the midfield zone involved Gerrard dropping and the full-backs pushing forward. As noted above, whenever Gerrard dropped deep to slide between the centre-backs and get safely on the ball, away from any Spurs’ presser, both full-backs but especially Manquillo pushed extremely high down the flanks. Then, after a short recycling process across the back three players, Gerrard would try a quick diagonal to the bombing forward full-back. It seemed this pattern was used as the back-up plan if Sterling couldn’t quickly get on the ball. In contrast to the above pattern, here the aim seemed to be to bypass the midfield zone altogether, hence minimising the risk of Liverpool being pressed there.

In a way it was logical to see Moreno being more active to push forward. Not only he is the more natural attacker, but down the right Liverpool’s pair had to deal with greater wide danger. Manquillo had to keep an eye on Chadli, who has both the pace and the height to be a viable target for dangerous passes in behind, not to mention his infield runs to become a second forward. Meanwhile Henderson had to often quickly run wide to confront the overlapping Rose. Meanwhile, on the left, Lamela’s tucked in position meant Moreno was often completely free to bomb forward, knowing Allen would be quick to get back and/or across to deal with Lamela.

The problem though was that, surprisingly, Gerrard was very wasteful with his long passes. Several times the team did everything as presumably planned – the specific movement of the players to drag Spurs’ attacking midfielders across the pitch to secure free passage for Gerrard to drop in and Moreno to push forward, the methodical recycling at the back to further drag Spurs around – only for Gerrard’s diagonal switch to be at times very wayward.

All of the above meant it was very hard for Spurs to get into their pressing rhythm, closing down Liverpool quickly and efficiently in the midfield zone. Additionally, given Liverpool’s formation, it was hard for the home team to arrange themselves in a good pressing shape. The way both formations matched up, it wasn’t clear how Spurs’ pressers should have acted and whom exactly to close down. As hinted earlier, the main confusion was across the band of three behind Adebayor. With Gerrard dropping as more of a third centre-back, Liverpool looked like a 3-4-1-2 formation at times, with the ‘1’ (Sterling) often getting alongside the midfield duo to increase the midfield bodies. This meant the home team’s 4-2-1-3 shape didn’t have any natural opponents. The logical solution would have been to see the wide men join Adebayor pressing Liverpool’s back three, with the double pivot pushing on to press Liverpool’s midfield duo, leaving the full-backs to battle against each other. But not only would this have left Vertonghen and Kaboul vulnerable to the pace and trickery of Balotelli and Sturridge 2-v-2, but with Sterling dropping back, Liverpool would’ve always had a spare man in midfield to pick up the ball and quickly get past players. The alternative variant would’ve been to see the wide man pushing infield to join Eriksen to press Gerrard, Allen and Henderson with Capoue and Bentaleb pushing on Sterling, leaving the full-backs to again deal with each other. But again, not only would this have left the centre-backs hugely exposed, but it was hard to imagine Adebayor dealing with both Sakho and Lovren, not to mention Mignolet, who would have been the additional passing option to recycle the ball across the back.

The only time Spurs managed to surround a Liverpool player in possession came in the 26th minute, when Eriksen and Lamela, helped by Bentaleb, crowded out Allen in the midfield zone. Logically the ball was taken off the Liverpool player with Spurs looking to threaten on the break. But even here, the visitors dealt with the danger with Allen intelligently making a tactical foul, pulling back Bentaleb’s shirt and preventing the danger developing.

With Liverpool dealing supremely well with the potential danger of Spurs pressing them aggressively; there was the need to cover for the other danger – the threat coming from the roaming movement of their front quartet. It was here where Liverpool impressed massively as well, even if their approach to that potential issue was a bit risky.

First, there was the difference in Gerrard’s defensive role. In contrast to the majority of the matches he has played in that position, here he looked more like an advanced centre-back than a deep-lying midfielder. This meant he was evidently more concerned to stay firmly ahead of the centre-backs and not venture too far forward or wider away from that position, instead of being attracted to the ball and running around trying to regain it via his trademark tackling or little bodychecks. A few times, especially early on, Gerrard’s rather static positioning left Eriksen to wander around freely, with the Dane a couple of times receiving the ball freely and initiating some dangerous passing exchanges in attack for his team. But despite this, it was clear the danger between Liverpool’s lines was greatly reduced, especially when compared to other games with Gerrard in that position playing more like a ball-winner than an anchor man. The main reason was that this new Gerrard role suited him more. Instead of running around and trying to act as a ball-winner, therefore being exposed by his lack of mobility and recovery pace (in that he could be easily bypassed, especially if he ever tried to stick tight on his direct opponent) and his team (if the space between the lines opens up with no-one in particular to cover), his firm positioning at least helps that vital zone between the lines remain much better protected. Even if the opposition advanced midfielder is left free to roam around, there would be less space for him to thread dangerous through balls, as Gerrard staying put helps plug the gap in the ‘D-zone’.

Then there was the thing that made Liverpool’s overall defensive approach look like a risk – the team kept such a high defensive line, as the centre-backs were often literally touching the central line. Obviously the aim was to push up the backline as high as possible in any given moment to further squeeze the space towards the midfield zone and make Spurs’ potential pressing redundant due to Liverpool having plenty of players in close proximity to pass out of any trouble relatively easy.

The risk here was that any potential lofted pass in behind could release one of Spurs’ mobile attackers through on goal. That risk was more of a gamble when considering Mignolet isn’t a natural at quickly coming out to sweep up any such potential danger. That theoretical potential risk quickly revealed itself in the game. Twice Bentaleb’s long passes from deep broke the defensive line and sent a runner in behind. In the first situation Mignolet somehow and very awkwardly managed to came out and prevent Chadli having a clear run at goal. Then, a minute after Liverpool’s opening goal, Adebayor latched on Bentaleb’s superb pass to get in behind the centre-backs and through on goal. Unfortunately for Spurs, his lob beat the keeper but also went a bit high and missed the target.

Anyway, although there was a certain risk associated with that defensive approach, presumably the nature of the back four simply dictated using it ahead of any other alternative strategies. All four of Liverpool’s defenders are naturally front-foot players, with their initial reflex and overall thinking being to stick tight on their opponent and quickly engage with him to claim the ball instead of retreating back to cover zonally. Arguably the mitigating factor was that all four of them have the pace and mobility to quickly recover in time if initially beaten. Ideally, the risk associated with this would have been even more minimised if there was a natural sweeper-keeper who could comfortably and decisively patrol the zone in behind the back four.

This meant that with the back four preferring to push on – there would have been more of a risk to ask them to fulfil an approach which is against their natural style and thinking – the whole of Liverpool’s team should have followed suit with the overall defensive approach based entirely on that particular action. With the team keeping such an aggressive and high defensive line, the midfielders had to follow and press from ahead. That’s why instead of seeing Allen and Henderson sitting deep and narrow close to Gerrard as in the Man City game, the two of them pushed forward, joining Sterling to press from ahead, aiming to ruin Spurs’ passing flow early on and cut off the link between the double pivot and the band of roaming attacking midfielders.

With the defensive line being aggressive and so advanced, in addition to the midfielders looking to press, this suited Gerrard’s new role. Or it could be as easily said that Gerrard’s new defensive role was as a direct result of how the team as a whole and the players behind and in front of him behaved when out of possession. The back line pushing forward to squeeze the space towards the midfield zone meant there was little space between the lines, so Gerrard wasn’t asked to cover huge ground. Then with his midfield teammates timing their pressing actions, his role was all about staying put and near to the centre-backs, acting as the required third defensive body and main anchor.

Due to the nature of the back four alone, the whole defensive approach of Liverpool changed its main emphasis. Previously, with at least two players in the back four preferring to retreat and defend zonally closer to the penalty box, the onus was on the midfielders and Gerrard, as the deepest midfielder, to offer that positional cover and protection between the lines from ahead. Now, with the back four pushing up and naturally squeezing that space, there was less emphasis on the midfielders and Gerrard to offer that shielding presence. This liberated the shuttlers to do defensive work that suits their dynamism and individual skills (all of Allen, Henderson and Can are better pressers than pure anchor men as they lack the specific defensive nous required for such a defensive-minded role), while it meant Gerrard’s lack of mobility and defensive awareness was going to be less exposed (as his main role was to just stick firmly ahead of the back four and do his best positionally). And as he showed throughout his career, Gerrard could be useful defensively, but only if given a specific task and not asked to do anything extra. He has the discipline to adhere to his instructions, especially when they don’t force him to assess situations and decide how, when and where to position or engage the opposition. Effectively, in such a set-up, Gerrard is more of a spare man, rather than a pivotal defensive player given the nature of the system and his exact position within it. Plus, with the ability of the back four to chase back and recover, there is even less onus on Gerrard to do anything else than simply try to plug the gap ahead of the centre-backs and not leave them too isolated.

With all of the above it was evident Liverpool completely dominated the midfield zone, both in and out of possession. This was both the main reason for their defensive stability but also the platform for the team looking so dangerous in attack too.

Liverpool attacks down the channels

Based on the chosen formation by Rodgers, Liverpool had different routes to goal. In case Spurs pushed up and risked pressing them high up, there would have been the danger of quickly feeding the front pair and letting them run riot 2-v-2 against the not so mobile centre-back pair of Vertonghen and Kaboul. Then, as noted above, with Sterling – and often one of the forwards too – dropping to assist the build-up play, Liverpool always had enough bodies to get on the ball and quickly surge forward, initiating quick and purposeful passing moves.

The nature of this Liverpool XI, especially within that formation, meant the visitors were extremely direct and penetrative in attack. The two full-backs were quick to push forward, in addition to being the type of players capable of surging off the ball or when on the ball both having the abilities to provide a neat through ball or drill a dangerous cross into the box. With Allen, Henderson and Sterling, the midfield unit boasted three (especially the latter two) extremely dangerous midfield runners. With the front two being always on the move, posing positional dilemmas and constant confusion across Spurs’ back line, there were always going to be enough opportunities for the runners coming from deep to be a threat in the last third. With that combination of pace, power and technique, in addition to the usual crisp passing, Spurs were simply doomed to struggle to cope with the danger provided by Liverpool.

Although the diamond formation is naturally geared up towards overwhelming the space through the middle, Liverpool caused their threat mainly by exploiting the space down the inside channels. This was partly down to Spurs having a double pivot, with Bentaleb evidently sitting nearer Capoue in this game, but partly down to the overall set up provided by Rodgers. As the above mentioned situation from the third minute showed, Liverpool put emphasis down the channels. There they aimed to overload the opposition, dragging their players over there to then have a runner coming from deep or wide to penetrate the vacated space off the ball.

Although the first goal came following a basic counter-attack, with Liverpool regaining the ball in midfield then breaking forward and within a couple of passes squaring the ball for the goal-scorer to tap in, it also showed the emphasis of the team to overload the wide areas. In that situation, as in many others, one of the forwards – here it was Sturridge – was positioned down the flank, which meant he could receive the ball and drag the attention onto him, leaving Henderson to ghost forward unnoticed to receive a pass from him to then square a great cross for Sterling to convert at the far post. A similar attacking move – by nature if not exact execution – this time down the opposite channel, led to the penalty incident at the start of the second half, with Allen surging forward in that space through the inside channel where it was unclear whose responsibility from the Spurs camp it was to initially mark or eventually track him back.

Another good aspect of Liverpool’s attacking strategy involved the team actually choosing situations when to commit more players deep into Spurs’ half and press them hard, mainly from goal-kicks. Several times this led to the home team conceding possession cheaply inside their half, gifting easy chances to Liverpool to counter-attack. Twice in the 15th minute, Liverpool lined-up high up the pitch to close down when Spurs tried to play it out short from Lloris’ goal-kick. And twice Pochettino’s players succumbed under the pressure rather too easily.

Time and again Liverpool played out safely from the back, then proceeded to develop quick attacks down the inside channels, based on the initial overloading of their players assisted by the slick passing exchanges from the players – on top of their ability to quickly interchange positionally off the ball. As with the pressing issues, Spurs looked unable to get to grip with what was happening and how exactly to try and deal with it.

Spurs’ attacking issues

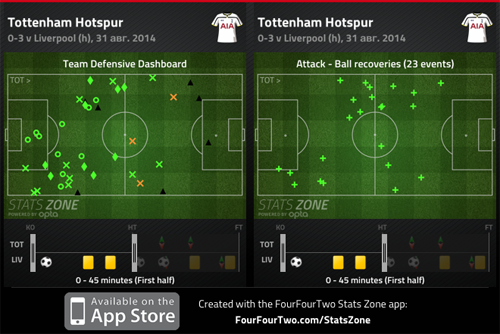

Throughout the whole of the first half it was clear the home team was struggling in attack. Simply said, they just lacked ideas how to approach breaking down Liverpool’s defensive system. With Spurs unable to press, their main routes to attack were either to catch Liverpool on the break or simply hope to get hold of the ball for a little longer to get the ball to their creative players for them to invent something.

The main issues for Pochettino’s team going forward were two-fold. On one hand their passing seemed ponderous and lacking the drive they displayed up to now in the season. This was as much down to Liverpool’s measured pressing, obviously making it hard for them to pass the ball around freely, but also to how slow and lacking invention Spurs’ deep-lying players were when on the ball. Apart from Bentaleb’s two long passes from deep towards Chadli and Adebayor, the team’s double pivot seemed overly cautious and unambitious with their passing, looking to knock it sideways, looking to feed the full-backs instead of trying to find ways to gain territory and join in passing exchanges with the attacking midfielders.

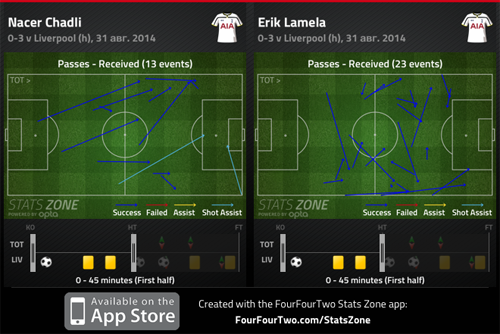

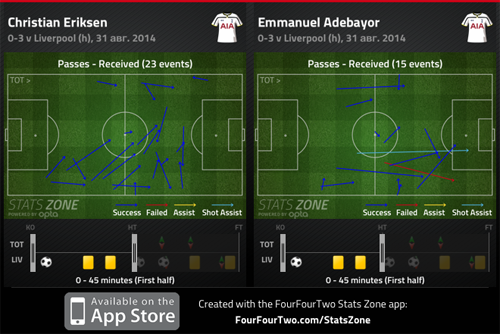

Another problem was that although Eriksen generally tried to roam around and often drop deep to help link up the team, neither Chadli nor Lamela looked as fluid with their movement as they should have been in such situations. With Rose and Dier doing their best to bomb forward and maintain attacking width, in addition to the double pivot not providing the required movement diversity and send additional runners higher up the pitch, Chadli and Lamela could have tucked infield and simply looked for ways to get in that space either side of Gerrard, or at least between Liverpool’s captain and his teammates pressing from ahead. But they remained either overly static or rarely received the ball in a pocket of space and on the half-turn, ready to spin away and do something dangerous with the ball.

The same could be said for Adebayor as he rarely looked to drop deep or drift wide to help out offer additional passing angles to try and drag Liverpool’s defensive players around. But at least he could be at least partially excused, as his advanced positioning provided an extra dimension and enabled his team to search for those long balls to beat Liverpool’s high line. He got very close to exploiting this, when he got the chance to equalise a minute after Liverpool went ahead but his shot lobbed both the keeper and the goal.

With all of this in mind it’s easy to see why Pochettino’s players struggled to create dangerous attacking moves, let alone genuinely goal-scoring chances, by themselves. Apart from that Adebayor chance, the team’s best attacking situation came following poor individual errors from Liverpool’s defenders. The first such situation came in the 23rd minute, when a poor Sakho pass gifted the ball to Eriksen. The Dane was quick to slip Adebayor in behind and if it wasn’t for the perfectly timed block-tackle by Lovren, the forward’s square pass would have found the on-rushing Chadli in a perfect goal-scoring situation. Something similar happened in the 41st minute, when this time Lovren conceded possession cheaply to Lamela, who played a quick forward pass to again release the Togo striker through on goal. This time the Croat defender’s superb pace and composure – to recover in time and clear the danger by tackling Adebayor – was crucial.

The next situation – in the 42nd minute – illustrated the risk of having two centre-backs who like to push up and engage the opposition rather stay back and cover for their partner when he runs forward to confront the attacker. Both Sakho and Lovren found each other rushing to block Adebayor for the same ball, with the ball simply fizzling past them to reach Chadli, now completely unmarked on the edge of the box. Fortunately for Liverpool, his shot was straight at Mignolet, who was forced into yet another superb block-save.

Start of second half

Apart from the double pivot and the front quartet struggling to execute the usual pass and move combinations associated with a Pochettino team, the main problem for Spurs from the first half seemed to be the lack of extra attacking bodies pushing forward to help distract and overload Liverpool in the final third and especially between the lines. Capoue was doing his job to try and set the team’s passing rhythm from deep, but with Bentaleb largely duplicating his role and keeping the same position, Spurs struggled to provide the required extra movement fluidity and/or the on ball fluency to assist the front quartet.

The thing was that with the starting personnel, arguably Spurs had little capability to offer something else or try to rectify the issues seen in the first half. The team couldn’t really press Liverpool back unless they risked leaving themselves even more exposed at the back. In the meantime that starting XI couldn’t really provide the missing spark, even if the front quartet were to come out rejuvenated by Pochettino’s team-talk at half-time. Even if Pochettino was to order his team to push even higher up and ask his full-backs to play more as wingers to allow Chadli and Lamela infield, it’s hard to imagine either Bentaleb or Capoue being capable to provide the additional attacking thrust coming from deep in midfield.

That’s why a half-time substitution was imperative in order to introduce a player able to provide that missing extra to make Spurs more direct and penetrative. Even if Paulinho was once again strangely omitted from the match day 18 in the league – otherwise he would’ve been the obvious choice for the role of the additional midfield runner – Pochettino had options on the bench with the likes of Dembele, Holtby, Townsend and Kane.

The obvious solution would’ve been to replace Bentaleb with one of Dembele or Holtby as both are players capable of offering that extra directness on the ball to help get past Liverpool’s defensive wall or simply increasing the passing tempo and providing an extra dimension with additional runs from deep. The other possibility was to replace Bentaleb with Townsend and play him on the right with Lamela moved infield and Eriksen dropped alongside Capoue. This would have provided Spurs with an extra dribbler and more invention from deep in midfield. The final alternative was to go even more direct, introducing Kane for Bentaleb and switch to a 4-4-2 with Eriksen again in midfield, Chadli and Lamela on the flanks.

But for all his options, Pochettino chose not to do anything, simply counting on his presumably harsh team-talk to improve his side to the point of overcoming all of the first half issues. Not only were Spurs unchanged for the second half, but inside two minutes they were already two goals down thanks to a very stupid action from Dier to concede what was a clear, if soft, penalty. The game was now arguably beyond Spurs’ reach, not least because of how composed and mature Liverpool continued to look in the second half too.

At least when Pochettino decided to make substitutions, they seemed in theory suitable and designed to help improve some of the attacking issues displayed by his team up to now. Dembele replaced Bentaleb in midfield, with Townsend coming in for Eriksen to play on the right with Lamela moved central. The two changes were obviously designed to increase the dribbling skills and overall penetration of Spurs, as it was clear the initial plan based on pass and move combinations proved ineffective. Pochettino replaced two ball-players, introducing two dribblers.

But not only did Pochettino’s tactical tweaks come too late – only after Liverpool scored their second and were now firmly in control of the game and not at half-time when Spurs had the chance to come out and claim a dominating position – but also, once again, a poor individual mistake cost his team another goal. Seconds after his cameo, Townsend received the ball on the right flank but couldn’t stop Moreno robbing him and storming past him to score what was a lovely goal from a brilliant solo action. Not only was Townsend too easily dispossessed and then beaten for pace, but not one of his teammates were quick enough to engage Moreno and limit his shooting angle.

Last 30 mins, Liverpool seeing out the game easily

At 3-0 it was game over for Spurs. But as much as how obviously Spurs’ heads dropped after the second, and especially after the third, goal, Rodgers expertly closed down the game, being quick and proactive to make tactical changes for this to happen.

A minute after the third goal, Can and Markovic came in to replace Allen and Balotelli respectively. This signalled a change to a 4-1-2-3 formation with Sterling (left) and Markovic (right) on the flanks. Obviously the aim behind these subs was to change the team’s overall emphasis. The change in the shape and personnel signalled a change to a much more passive, reactive and even defensive-minded approach to the remaining time of the game. The team was now going to defend in a deeper and narrower 4-1-4-1 shape with Can and Henderson now firmly just ahead of Gerrard to create a second bank of four ahead of the backline. Still, with enough pace retained on the flanks and up front, Liverpool would have continued to be a danger on the break.

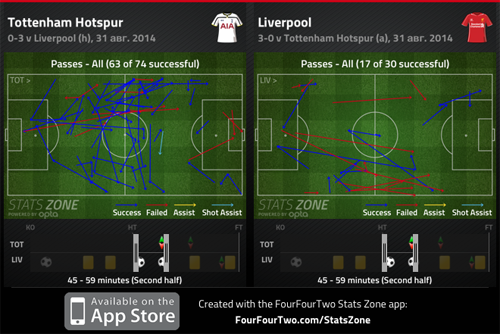

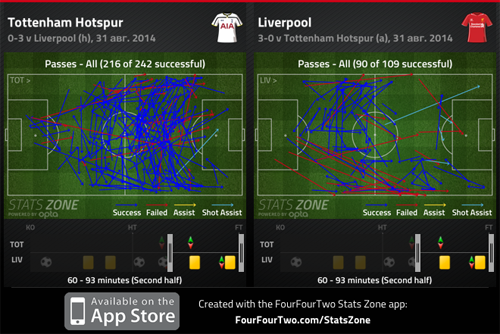

Although in the last 30 minutes of the game they had more than double the passes of Liverpool, the home team lacked any kind of attacking drive, continuing to display a total lack of penetration. The tempo in that period slowed down to the point of Tottenham looking too ponderous and often attacking at a walking speed, which obviously suited Liverpool as it gave them enough time to get men behind the ball and organise themselves at the back. With the visitors now defending deeper with two banks of four, patrolled well by Gerrard in between, Rodgers’ players denied any space for Spurs to invent something dangerous in the final third.

What’s more, it was actually Rodgers’ team that looked more threatening in attack. The pacey front three of Sturridge, Sterling and Markovic, helped keenly by two powerful box-to-box midfielders (Can and Henderson) displayed some lovely touches and created a few dangerous counter-attacks. Sterling’s solo run in the 70th minute, following Can’s powerful forward run and nice little pass to him in the build-up, came closest to add to the goal tally if it wasn’t for the peculiar finishing the winger applied that ended up too weak and so easy for Lloris to save.

Post-match thoughts

After three games (or to be specific two and a half, as in the second half of the last meeting between them, Pochettino’s half-time changes ruined Southampton’s dominance and gifted the game to Liverpool) of battling Rodgers tactically, here Pochettino was totally outsmarted. Spurs struggled to get going on all fronts in the first half, with their expected pressing completely bypassed and their biggest attacking threat nullified. In the second half, a combination of Pochettino’s earlier tactical actions and individual errors handed the game to Liverpool on plate.

For Liverpool this was a brilliant all-round performance. After the very poor game against Southampton, the team improved to the point of playing a very good first half at Man City. Here, Rodgers’ team performed defensively and offensively superbly throughout the whole game. Liverpool’s initial approach was very mature and professional, even if a bit risky. Still, even that potential risk – bar a couple of instances – was nicely mitigated by how balanced, as a whole, the team looked defensively and offensively. Even Gerrard, arguably for the first time under Rodgers, looked surprisingly good defensively even if uncharacteristically poor on the ball. Then the way the team pro-actively closed down the game after the third goal was exemplary as well.

All the credit has to go to Rodgers for the detailed tactical work done by him for and during this game.