In some ways Roy Keane is a complex character. A great player, and a fighter, he is unfortunately, but undeniably, intellectually simple. He understands aspects of football, clearly, but like so many who played the game, he can’t analyse or articulate it. He makes his points as if anyone who disagrees can expect a swift punch – which isn’t how discourse should work.

He played football with a steely on-pitch intelligence, but that doesn’t mean he can talk with any wisdom about the game. Because to do so takes self-awareness, the ability to reflect and analyse. It takes humility. It takes admitting your mistakes and your flaws.

With brutality he purposefully ended a player’s career, walked out of a World Cup like a prima donna (or that’s how he would portray someone who did the same), and he was kicked out of the club he had served for years because in the end he was too much of a pain in the arse.

As a manager he was a failure, albeit he gave it a try. He also played in a team that failed to defend its title on numerous occasions, and any time it did so it did not signal the end of Manchester United’s longer term prospects. He played in games where United were thrashed, in seasons when they lost plenty of games, and he got sent off and let his team-mates down time and again by being a meathead. You might want Keane on your team, but just as you wouldn’t want him in the opposition team you also wouldn’t want him near you as a manager, coach or pundit.

Earlier this season, when he said on that he would have punched David de Gea because of a mistake the keeper made, it was the time to cut him loose. After all, everyone knows that the way to deal with someone who makes a genuine error in life is to punch them. Anyone with an abusive parent or teacher knows how well being punched for your mistakes works out. Such mindless aggression may work at times on the pitch, in the heat of a battle, but not in the adult world of ideas.

It’s “colourful” TV, in the way that watching people playing Twister on a plastic mat covered in their own faeces would draw viewers. That’s the state of modern discourse, modern hot-takes and indeed, hot-headed takes. Sky employ him because he’s a “character”. While it can be more entertaining than some dull, uninsightful platitudes from some other ex-pro, it’s no more helpful.

It doesn’t help that it’s hard to make nuanced, well-rounded points on Twitter, or in brief soundbites on TV analysis crammed between several ad-breaks. The world has elected presidents based on their ability to be vile trolls on Twitter or in press conferences, as stupidity and dumb gut-feelings were celebrated as “telling it like it is”; while some on the other extreme side of the political aisle argued that “nuance” is a bad thing. If you’re going to argue that nuance and context are bad things, then you’ve lost me, just as I’ll oppose hardman quasi-dictators. We need insight, not bullies. We need nuanced analysis, not oversimplified claptrap.

While I’m going to get onto the football, it’s worth just outlining the ignorance that passes as analysis in modern life. If you don’t understand confirmation bias, cognitive dissonance, the Dunning-Kruger effect (as a placeholder for people thinking they know more than they actually do), and various other faults in the way we all think, you are likely to be propagating flawed ideas. (And even though I can sometimes let my emotions do the talking, it’s still often backed by data. Even my rants against referees.)

We don’t need gut-based guff, just as we don’t need an eschewing of nuance and context. We need data – facts – and wise people capable of analysing them properly.

Equally, wise people without the correct facts – fumbling in the dark – are not going to help, as all decisions and conclusions will be based on incorrect inputs. Great data without someone wise enough to correctly interpret it won’t help, as it’s just a mass of information. Throwing out context and throwing in fact-free feelings are why so many countries are in a mess right now. It’s why the world is so polarised. It’s why Covid-19 has caused so much damage in countries that were not paying attention to the lesson of SARS.

While “both-sidesing” actual Nazis who commit actual violence or genuine hate speech is a bad idea – they don’t deserve platforms – the ability to see both sides of any story, even abhorrent ones, helps to understand why bad things might happen. For instance, by trying to understand Neo Nazis (what was driving them into such a demented way of life?), some sane and patient people have talked extremists out of their cult-like thinking. They were talked off insane ledges by rational people, not by shouting at them or threatening to punch them (as that just gives them the feeling of the moral right to punch people back).

But those are extreme examples, and this is not an article about Nazis, either the small number of fucked-up real ones or the hundreds of millions of people whose crime is to disagree with someone on the internet (“Nazi!!”). We need to learn to think properly, discuss complex ideas and understand how our emotions (while sometimes accurate) can be misleading. Before we can even understand football we have to understand how to think and how to analyse. If our analysis is that the goalkeeper who made a howler needs to be punched, something has gone badly wrong. Fear can force people try harder if they were otherwise slacking, but it makes thinking clearly more difficult, and taking risks more frightening. Fear kills creativity.

Binary thinking is everywhere these days. The limited space for more than a few words on Twitter, and the instant emotional reactions people have to what they read – how communication is gut-based and not brain-based (and how people react before they’ve even understood or even read the information) – has dumbed down the left and the right extremes to simplistic jargon: hot-takes, takedowns, pile-ons, and many of the psychological phenomena that are associated with poor mental health, i.e. catastrophising, black-and-white (or binary) thinking, oversimplifying every issue, mind-reading (assuming what other people think rather than knowing what they think), and straw-manning the opposition viewpoint, to name just a few.

You can “win” the debates, get the mic-drop, but it ultimately leads nowhere as no one has their opinions altered, and all you’re doing is playing to the gallery within your own bubble; it’s all just junk calories for the mind.

This affects everyone, even those not on Twitter.

(I limit my tweeting time judiciously these days, and only occasionally read replies. But I also admit that I am rarely my “best” self on Twitter, as it just draws you into the trap of instant gratification. My thoughtful tweets are often ignored; my less insightful tweets amplified by thousands. Even so, I still try to resist tweeting just to get likes and retweets, just as we don’t do fluff pieces on TTT; I’m not here to just tell people what they want to hear. I am here to give my honest view, and people can like it or lump it. Sometimes I will be wrong, too.)

It then spreads into all reaches of the media, as the media and their gatekeepers all still assemble on Twitter. The internet is full of smart football analysis in various corners of the web, but a lot of it gets lost in the noise. While the internet could have spread great information, it has been more successful at propagating misinformation.

(Facebook is less popular with the media, and seems full of conspiracy theorists who reinforce their views of reality with each others, albeit some conspiracies can prove to be true. At least Instagram and TikTok are only full of vapid, soulless videos of heavily-filtered faces desperate for attention in ever-smaller chunks of “content”. If someone were to TikTok themselves and a group of friends playing Twister on a plastic mat covered in their own faeces it would go viral, especially if set to a thumping track with some sassy lip-synching and strange emoting. If Roy Keane were to join in, perhaps punch a few people, it would be trend like crazy.)

Again, this article isn’t about social media, but it’s all part of a dumbing down that can be seen in football punditry – albeit TV analysis has never been the most insightful. Roy Keane being angry will always get a good number of retweets and YouTube eyeballs. People will always rubberneck at car crashes, but ultimately it serves no purpose (you’re never going to like what you see), and risks further harm.

So, people tend to reach insanely simplistic conclusions because there isn’t the time or the space to go into more detail, and even if they did, a lot of people would say “tl;dr”. Indeed, this is a clear tl;dr article. Not everyone has a spare 30 minutes to read something, after all. Not everyone has a spare 30 seconds, it seems.

Sometimes there may be truth in a simplistic conclusion – but of course, it will be too simplistic; leave out too much context, avoid too much nuance. Sometimes it will just be plain wrong, because basing conclusions on how something feels or looks – the “optics” – is dangerous, when so much in life is an optical illusion, and counterintuitive. Things that appear simple can be incredibly complex. The sky seems to be full of merely thousands of stars, but the universe is actually estimated at trillions of galaxies, containing 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars, give or take a few.

All that said, let’s look at some simplistic conclusions.

Simplistic conclusion: Liverpool are nothing without Virgil van Dijk

Actually, Liverpool were still top of the league without Virgil van Dijk.

However, add season-ending injuries to Joe Gomez and Joel Matip and it’s then not about just missing van Dijk but missing his two key partners, and his two key understudies, depending on which one was alongside him and which one was on the bench.

Indeed, when Liverpool were top of the league, and getting results even with Matip and Fabinho as a very effective pairing, I said that injury to either would probably be a bridge too far, and cause the season to collapse. Both soon got injured; Matip for the rest of the season. The season collapsed. It wasn’t a certainty, but it felt likely.

Last season, until the league title was won, Gomez was absolutely sensational (he was ropey after lockdown and the league was won, but he was’t alone). In the run-in in 2019-20, including the successful Champions League final, Matip was arguably even better than van Dijk, as I argued to some derision at the time. Gomez also had a spell being better than van Dijk – for a while he belied his years, with a brilliant all-round game.

But of course, while Gomez and Matip had spells looking better than van Dijk, most weeks van Dijk was the constant beside them, being 8/10 on his bad days, while the guys alongside him were 9/10. Then there were spells where van Dijk would be 10/10. Players were even afraid of him because he smelt too damned good. And he’s not just a defender: he scores goals, and played some role in the build-up to 50% of Liverpool’s goals last season.

So yes, he’s the best defender at Liverpool, the best defender in the Premier League, the best defender in Europe and the best defender in the world. That’s all agreed in most polls over recent years.

But Liverpool didn’t just lose the world no.1, they lost two other centre-backs who I’d rank in the top 10 centre-backs in the world from 2018-2020, perhaps aided in that form by his assurance. Even Fabinho is a superb centre-back, but then he got injured as well.

Nat Phillips, with zero Premier League games going into this season, and young Rhys Williams, with zero games above non-league level, will grow from their experiences this season, just as a young van Dijk took many years to make a proper mark in Dutch football, and only won his first cap when he was four years older than Williams. At 19, van Dijk had big potential, but was raw. He was 26 before any big club in a major league (i.e. Liverpool) signed him.

Phillips and Williams are unlikely to end up anywhere near as good as van Dijk, because van Dijk is the most complete centre-back of his entire generation. So you can’t have a van Dijk in reserve. You can’t have a 6’4″ gigantic-leaping, stunning-heading, quarterback-passing, fast-sprinting, goalscoring, ball-nicking winner like that hanging around as 4th or 5th choice. Maybe the next-best players can be 85% as good; then, after that, maybe 60% as good. Go through to the youth team and U23s, and they may be 30% as good at this point.

And if you have two other outstanding centre-backs – 85-90% as good – who are also badly injured, you are going to arrive at ever-worse solutions, through no fault of their own, and no fault of the manager. All resources in football are finite. Liverpool had four centre-backs this season, including Fabinho, and at one point all four were injured.

If Paul McCartney and John Lennon had left the Beatles in 1966, then no one – not even the best from rival bands – could join George Harrison and Ringo Starr to make them as good. There would have been no Sgt Pepper, but whoever joined may still have written some nice tunes. There aren’t any spare Virgil van Dijks, just as there was not another Lennon or McCartney.

And, of course, that’s before getting onto the years of shared wavelengths that the Liverpool defenders had accrued, just like how Lennon and McCartney understood each other’s “game” to an uncanny degree. (Of course, they weren’t anything special when they started off, as a skiffle band, doing covers and writing derivative ditties, as young kids. They then spent years in Germany, working as a band night after night, and their “overnight success” took many years.)

Simplistic conclusion: Thiago is the problem

The issue I have with this is that when Thiago came into the team it was late in the game at Newcastle, in what was destined to be the second draw from a game people expected the Reds to win. Matip had already become the third main centre-back to be injured, although this was before he was ruled out for the season.

So the rut was already in place, the goals had already dried up for about 150 minutes. Alas, Phillips was playing at the back and spent the game giving the ball away and making late tackles (he recovered well against Spurs as a sub, and at West Ham. He seems a good honest pro with potential, as I stated when I first saw him aged 19, whilst never looking remarkable in any way; as a Slow Giant, his time is likely to be aged 26 or 27, but at another club).

The defence was nervy, as it had been as soon as Matip went off early against West Brom when leading 1-0. A glaring weakness at the back undermined the rest of the team; almost like a fear of accelerating as they’d just discovered they had no brakes.

There were all kinds of issues affecting the injury-hit team, and Thiago was not at full fitness after several months out. He was slow in the tackle (and still is), but quick in his thinking with the ball, and quick with his feet. His play has generally been excellent, although against Man City he looked like a player who’d played a lot of games in a short space of time after several months out, and City were just too fresh and fast. Like Wijnaldum a few days earlier, it looked like he had hit the metaphorical wall, and was running in treacle.

Thiago has also made too many poor tackles (why does he keep sliding in?!), but otherwise his passing has been crisp and inventive, and often zipped direct to the feet of the attacking players, or into good spaces. So I don’t buy that he’s slowed Liverpool down. Liverpool had lost their way before he was fit again.

At times the full-backs have looked too tired to make the kinds of runs they have for the past few seasons, otherwise they would be more of a passing option. In the last three or four games, Trent Alexander-Arnold has finally found a bit more zip again, after looking very off the pace; but Robertson’s form with the ball has fallen off a cliff, perhaps due to fatigue, after years of raiding up and down the left flank for Liverpool, and leading Scotland.

Thiago was not responsible for Liverpool’s strikers – so reliable as a trio since 2017 – suddenly missing a run of gilt-edged chances, game after game, during the run of draws and defeats.

Normally, if Mo Salah had an off-game, Sadio Mané or Roberto Firmino (or both) would score. Or any permutation thereof, with at least one of them having a good day. That was the pattern, for years. Then the Reds hit a spell – like three bad symbols aligning on a slot machine – when they all couldn’t score, even with the goal gaping. Was that Thiago’s fault? Was it Thiago’s fault that the otherwise ultra-reliable Alisson gifted Man City two goals – and thus, the game – out of nothing?

He did not stop the referee from giving the Reds a penalty for a clear goal-denying handball at Southampton when a Liverpool player (Wijnaldum) finally found a great shot that was blocked by a defender almost with a goalkeeper’s spreading of the body, nor was he the Newcastle goalkeeper who grabbed Mané’s knee when Mané was faced with a tap-in from a yard. He was not to blame for some ludicrously good saves from Nick Pope in the Burnley goal – sometimes keepers have great games against you and then stink against your rivals – just as he wasn’t to blame earlier in the season, in his first start, for all the VAR mistakes that denied Liverpool a massively deserved win at Goodison Park, for which the VAR, David Coote, was duly demoted.

It was not Thiago’s fault that instead of playing in front of a world-class defence he was playing in front of rookies and stand-ins, with the midfielders he was supposed to play alongside also used in defence. Again, he hasn’t been perfect, but to me it feels like a case of correlation does not equal causation.

So it’s all far to simplistic. It’s like saying to someone with stage four cancer and severe Covid-19 that the patch of eczema on their foot is the main problem. You might not want to leave the eczema untreated, but you can’t focus on it when there’s so many other things to deal with.

Simplistic conclusion: injuries are not an excuse

I personally won’t engage with anyone who labels clear extenuating circumstances – the context, the nuance, the real-world facts – “excuses”.

The word “excuse” is loved by idiots, who see the world as either right or wrong. Obviously managers cannot be seen to be making too many “excuses”, but that’s about perceptions rather than reality.

Did you hear the story about the three-legged horse that won the Grand National? No, because a horse needs all four legs, or, alas, it gets shot. (But dogs are great with three legs! That said, I’m not sure a three-legged greyhound has ever won a major race.) Anything that scuppers your ability, against your control, is an extenuating circumstance. It is not an excuse.

Take Alisson yesterday. He had just missed the midweek game with illness. He then had his worst game in a Liverpool shirt – or more just a few mad second-half minutes. He seemed in a daze, with slow reflexes, giving the ball to City not once, not twice, but three times in three minutes, in a way I’ve never seen before in a football match. He then let a powerful but saveable shot straight through his hands.

Are the two connected? Almost certainly. You can’t say for sure, but to be ill one day and then have an atypical stinker so soon after is probably related. It’s not an unreasonable assumption; and is certainly better than blaming the goalkeeping coach under whom Alisson has excelled since 2018, when, two and a half years in, he finally has a total nightmare (Aha! It’s all John Achterberg’s fault, etc.).

Now, why didn’t Jürgen Klopp give Alisson another game off if he was unwell, or recovering from some illness?

The problem was that Caoimhín Kelleher was also out. (I’d actually heard before the Brighton game that the two clashed heads in training, which may of course be false, but it’s odd how both ended up missing games in the next four days, as if rotated on semi-concussion grounds. I thought the rumour was nonsense when I first heard it, as with all rumours, at a time when Alisson had yet to be officially ruled out; but for both keepers to be left out of games within a few days suggests it may have some merit. At the very least, it’s a plausible explanation.)

The alternative, alas, was Adrián, who was brilliant and bonkers when he arrived on a flood of adrenaline and good-wishes last season (applauded on for his unexpected debut by the Kop as a sub, as if some kind of crazy hero), helping the Reds to win the the title. But his form dipped, then dipped some more, until he cost the Reds the Champions League tie against Atletico Madrid. Then this season, it got worse still. He let in seven at Aston Villa after gifting them the first goal. He fell to third in the pecking order. He had done a great job overall in terms of definitely helping to secure that all-important league title (and some lesser silverware), but it was clear his time was up. Third choice feels about right.

In a make-or-break game, do you want to play Adrián, now 34, who has been poor in recent make-or-break games, or Alisson who is possibly not 100% well, and – even if he has recovered from the illness – may have felt totally okay, but not been right in some undetectable way?

In the end, Allison played … but played like Adrián.

That’s what being unwell or unfit can do to any top-level performance; just a few percent can make all the difference (just as, in cricket, players find the difference between an 85mph delivery and a 90mph delivery absolutely huge, as it’s the point where they go beyond a kind of comfort envelope; yet it’s only 5mph difference, which is walking pace).

The gamble was: is an unwell or possibly concussed Alisson better than a fully-well but limited (and confidence-drained) Adrián? To also have no Kelleher made it a tougher call, as Kelleher has proved an able deputy, and despite his inexperience (or maybe because of only playing a few times), has yet to stain his copybook.

As a result, Alisson now has to overcome one of the strangest few minutes from a goalkeeper I’ve ever seen in my life, but the fact that he hadn’t been well – in one way or another – in the buildup to the game would surely explain a lot of it.

The errors may permanently scar his confidence, but if he knows he wasn’t fully well, it would make it easier to overcome – just as a sprinter who pulls up with a hamstring injury is not going to focus on not having just run as fast as normal. (Or is it just an “excuse” if your hamstring snaps at almost 30mph and you just don’t want to run as fast because you just lack moral fibre? Are you just making excuses as you crawl towards the finishing line?)

It was just one more dilemma in a season of compromises and dilemmas: such as going with two well-paired central midfielders as centre-backs, who both generally played very well as Liverpool limited City to few chances (one non-penalty shot in the box for most of the match) before Alisson gifted them two game-changing and soul-destroying goals. The first pulled the rug from under the Reds, and the second was like a smack in the face with a giant haddock.

The new buys could have played, of course, and allowed Jordan Henderson and Fabinho to move into midfield. That might have worked out better. There are definitely reasons to argue why it might have worked.

Equally, the new guy/s could have spent the game out of line with the other three defenders to play City onside time and again, could have scored an own goal, could have got sent off for a late tackle, or whatever. Who knows? Then, the correct decision, with hindsight, would have been to not be so stupid as to rush them into the team, and that it was bloody obvious that Fabinho and Henderson should have started in the defence, as no one risks new guys in such a pivotal game, yada yada.

Either way, it was a compromise. Klopp either played midfielders who are excellent deputy centre-backs but not necessarily world-class centre-backs (though I think Fabinho could easily become one if required), whilst losing them from the midfield; or he played one or two new guys who have never played in the Premier League and only trained for a few days with the club.

Plus, one of them is just 20 years old and fresh from the Bundesliga; and while clearly having world-class potential based on so many astute observers of German and Turkish football, makes the kinds of mistakes that young, aggressive defenders make.

As well as being aggressive, he’s good in the air and good on the ball – with a huge ceiling – but had given away three penalties already in half a season in the Bundesliga. Do you want to start your new guys, before you’ve even taught them to swim, by throwing them in the deep end?

Simplistic conclusion: the squad players should be good enough to play every week if required

Okay, here’s a thought: good luck to any team trying to win the league with an average goalkeeper, let alone a 4th-choice goalkeeper. Yet who would even expect that to happen? Think of all that Peter Schmeichel added to Manchester United – the levels to which he lifted that team with his presence and his ability – and then think of his deputy. Then, go past his deputy into the youth team. Pick out the 4th choice, a pimply lad of 17, and how would he have fared in trying to chase down a league title? Remember, after Schmeichel left, United had poor seasons with keepers who were often otherwise pretty good (or had been before they buckled under the pressure), but nowhere near his level.

While admittedly only using three goalkeepers in big games so far this season, at times Liverpool have been down to 6th and 7th choice players in other key departments, and each time Jürgen Klopp has to go deeper into the squad he’s going to find increasing issues, as the most consistently effective players are the first choices. That’s how it works.

You can put four past Barcelona with two great strikers missing (egged on by the crowd as the 12th man, which added a psychological edge that scared the Catalan giants who were already a little frightened of the Kop’s power, not least the two players who had received its benefits over the years); but you can’t expect to do that week in, week out, with Divock Origi and Xherdan Shaqiri, who have proved their value as patient squad members happy to only play occasionally.

It’s no good buying backups who instantly want to leave, or who ruin the atmosphere by sulking or driving off in a huff if they don’t get a game. That’s what squad players are: good, and hopefully very good – but rarely brilliant. If they are brilliant, they probably won’t hang around too long. Or, they usurp someone in the team, and that player, if not prepared to fight for his place back, then wants out.

So, a quick counterfactual from history.

In 1983/84, would Liverpool have won the treble with David Hodgson, five league appearances (one start!), and Michael Robinson (24 league appearances, not all starts), swapping their appearance data with Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish, so that Rush played only 24 games and Robinson played 41; and Dalglish, instead of playing 33 league games, had Hodgson’s measly one league start? What are the odds that Liverpool would have been as good?

If you replaced two of Liverpool’s best-ever players with two of their most mediocre, what would have happened?

Of course, even that’s not an accurate analogy, as Liverpool’s defensive crisis would take Liverpool beyond the pecking order of Hodgson and Robinson – decent enough top-level players who knew they were not good enough for Liverpool (Robinson, who sadly died last year, was an astute pundit in Spain and very honest about how out of his depth he felt at Liverpool) – and into perhaps some young striker on the books who would never be destined to play a single minute?

But even apply it to the centre-backs of that season and you can see the problem Liverpool are facing now.

Both Alan Hansen, demigod, and Mark Lawrenson, slightly annoying pundit but an amazing defender with incredible pace and the best recovery tackle in football history, played all 42 league games in 1983/84. They had been together for three seasons by that point. They were a sensational partnership – and that partnership was available all season.

Gary Gillespie, the new young Scot, played … once all season, in the cup. But he was a good prospect, just not ready. Phil Thompson, club legend, was still around but getting on (his entire career would be over within a couple of seasons), and he played just once, also in a cup game. Neither of them played a minute in the league that season.

Now, Liverpool’s chances of wining the league with Thompson, past his best, playing 42 games alongside new, young and untested Scot, Gary Gillespie (who would not break through into the team properly, bar a game here and there, for another three seasons), would have all but evaporated. Even at his best, Gillespie (these days a pundit I enjoy as co-commentator on LFCTV) was never as good as Hansen or Lawrenson. He surely knows that. He was very good indeed, but not exceptional.

But even then, in this analogy, not only are Hansen and Lawrenson out for the season (or at least long chunks), so too are Gillespie and Thompson. So Liverpool would be trying to win the league with a defender from the academy or one of the many players for whom reserve football was their level.

So, I thought I’d better go through to the far reaches of that admittedly smaller squad* to find out.

(*Players were less ultra-fit back then, and the game much, much slower, so there were fewer injuries; players now need to be trained more like racehorses to be super-explosive, but it means both an increase in injuries and also makes it harder to play with an injury, given the difference between walking pace – which you used to see in the old days with injured players – and top speed. I always used to think of an injured defender, playing with an iffy hamstring, having to chase Thierry Henry. And football, prior to Covid-19, had greatly increased in speed and intensity since even 15 years earlier.)

There, in the depths of the reserves, I found out about John McGregor.

“A centre-half who was a Liverpool reserve for years but never made the breakthrough. Queens Park … sold him to Liverpool but five years later … McGregor had been released on a free transfer from Liverpool.”

Five years, and not a single game. Would Liverpool still have done remarkable things with a 5th or 6th choice playing consistently in 1983/84? We can’t say for sure, but we can guess at the probability.

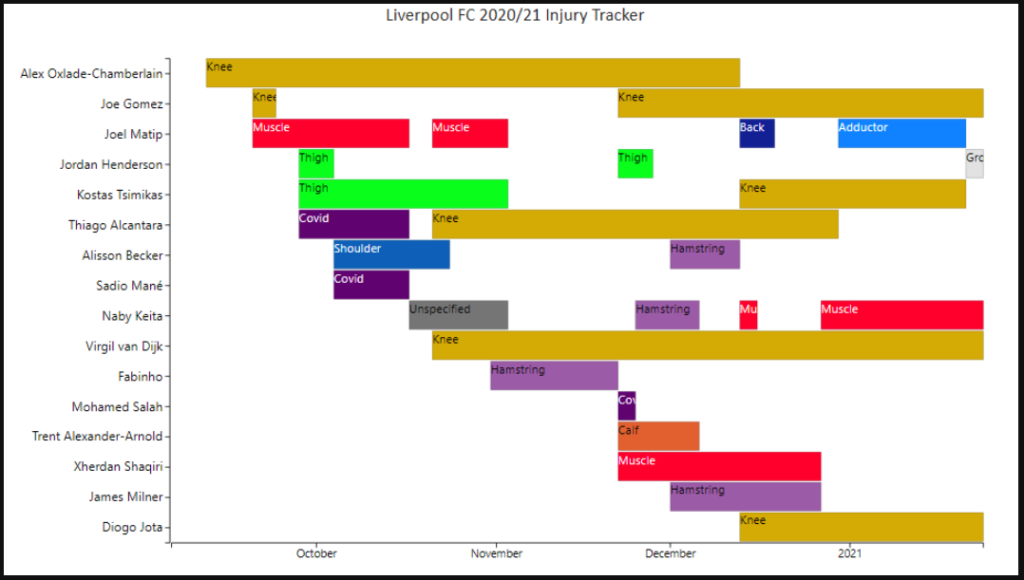

Now, Liverpool have also spent months and months without Thiago, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain (an effective player capable of 10 goals a season, who has been woefully out of touch since returning), Naby Keita (injury prone, but a game-changer), new left-back backup Kostas Tsmikas (who at the very least could have given the tired-looking Andy Robertson a rest), and the most lethal finisher based on time on the pitch, Diogo Jota, who is also great at taking the ball and ghosting past defenders, to unlock packed defences.

So, it would also need to take out Graeme Souness, Craig Johnston and Sammy Lee from the 1983/84 equation, as well as Hansen and Lawrenson (and their deputies). The Reds would be playing with a load of reserves.

You can argue that Jota should not have played in the game where he (and Tsimikas) got injured, but he was not in the red zone for muscle concerns, as he was low on overall minutes – and giving him extra time on the pitch was perhaps due to the lack of training during the flight-play-recover schedule of a Champions League game every midweek. (And as I’ve said before, he hadn’t started against his old team the previous weekend.) Obviously it backfired, but it was a calculated gamble that did not pay off. If players can’t train properly, they will suffer in other ways.

That pair were just two of at least seven major ligament injuries which were impact-based – often from bad “tackles” (nay assaults) – and therefore not due to poor physios or bad preparation work. It’s unprecedented. Joe Gomez’s injury at England training was freakish.

Liverpool have also had a few muscle injuries, but so has everyone else this season, with less time between matches and no proper preseason. The muscle injuries haven’t helped, but it’s mainly in addition to the season-ending ligament damage, with the latter causing the major problems. That has tipped the scales beyond an easily recoverable position.

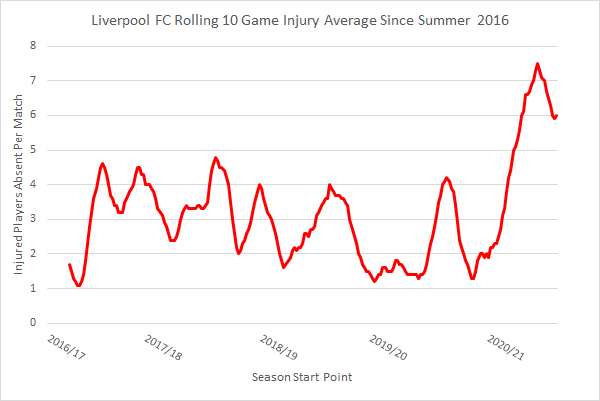

From this graph (below) that I asked Andrew Beasley to create after he’d been tracking injury quantities, you could make the point that Klopp can cope with 2-4 injuries as a running average, but 7-8 is unsustainable. Such a conclusion would be based on data, and entirely logical. It wouldn’t explain the whole story, but would be a clearly difficult situation to overcome. (It would certainly make more sense to me than saying it’s all Thiago’s fault.)

Then there’s Andrew’s graphic on the injuries, albeit I think it’s a couple of games out of date. This is no normal season.

Remember, Alex Ferguson once said of a season in the 2000s that Man United didn’t win the league because Paul Scholes was injured. Last season, people said that Man City missing Aymeric Laporte, who isn’t even close to van Dijk’s class, was a reason they were struggling. At times they left two fit centre-backs (including John Stones) on the bench.

Right now, City are without Kevin de Bruyne and Sergio Aguero. But they have an abundance of attacking depth – some stunning and interchangeable front-six players. And the injuries occurred when they were already flying. While that can still disrupt you, it’s better than if they happen when you are struggling, and worst if it happens in a position where even the cover gets injured too.

Last season, Liverpool coped brilliantly without Alisson for 11 league games and Fabinho for two months, as well as some other injuries here and there, because the team was otherwise in good shape and good form. It was manageable; it wasn’t utterly chaotic and beyond easing fixes.

Simplistic conclusion: Liverpool have been “found out”

or

Simplistic conclusion: Klopp has been “found out”

Aside from the Aston Villa game, where the Reds fell apart due to bad goalkeeping from the player now 3rd choice, and conceded three incredibly flukey heavily-deflected goals (but where the Reds’ high line looked increasingly problematic as the game grew more stretched), Liverpool didn’t have too many problems when most of the players were fit.

They swept aside Chelsea at Stamford Bridge and Arsenal at Anfield, outplayed Everton, won 5-0 in Atalanta, and while not always consistent, they were doing well. With a few injuries but still some senior centre-backs, Leicester and Wolves were thrashed at Anfield. Key players were missing, but not too many. Then, things spiralled.

Problems beget problems, beget problems. The more problems you have, the more new ones can arise. Every enforced compromise can have negative consequences; just as a player recovering from one injury is likely to suffer a compensatory injury to another muscle. Every change here or there has knock-on effects further down the line.

It feels like Liverpool are paying for the costs run up across the season so far, for things like points dropped (which removed all leeway), by the months of VAR madness (things like the points-costing decisions at Goodison Park); and the various injuries, that mean the overplayed players (Gini Wijnaldum, Andy Robertson, Fabinho, Jordan Henderson, et al) have often been running on fumes, because there wasn’t the depth due to injuries to make planned rotations and rest periods.

Changing a team by design – tweaking with some well-planned rest – is one thing; constantly changing due to a non-stop stream of new injuries, illnesses, etc., allied to long-term absentees, is far more difficult to overcome.

Adding a single rookie or squad player to a team of ten well-drilled as a team is easier than adding two or three squad men or rookies to a team that already includes two or three other squad men and rookies.

All this came after a disastrous truncated preseason in logistical terms, and none of the normal stamina is in the Reds’ legs. So how can you “find out” this Liverpool side if this isn’t the proper Liverpool side? All we’ve learned is that the 5th, 6th and 7th choice centre-backs are, unsurprisingly, not as good as Virgil van Dijk, Joe Gomez and Joel Matip.

Even so, bad finishing – just as teams finished badly when missing great chances against Liverpool last winter (failing to score with something like 50 efforts across a run of games) – has affected results beyond the level of the performances, although the performances have been patchy and at times lacking energy and/or confidence (in part due to missing chances and losing belief).

At times Liverpool, though massively deserved champions, rode their luck last season; at times this season their luck has abandoned them. That’s sport for you. Luck isn’t everything, and at times you make your own luck; but what did Liverpool do to merit so many snapped knees in one campaign? That’s why we talk a lot about the Black Swan concept on this site.

Against Man City, Mané’s poor header from the first clear-cut chance of the game, and Alisson’s gifting of two goals, changed what was otherwise a fairly equal match into a hammering. Bad luck can lead to bad decisions, as it can ramp up the pressure.

Missing all those big chances over the winter heaped pressure onto Liverpool. Such runs happen, and even if you turn the corner, you still have the pressure of all those dropped points. Just as there’s scoreboard pressure, there’s league table pressure. It gets easier when you’re 15 or 18 points clear at the top.

And it was always going to be harder defending the title anyway; that’s taken as a given, especially in a country where, in the past decade, five different clubs have won the title (Man City, Man United, Chelsea, Leicester and Liverpool), and there’s a Big Six often expected to be challenging, including Arsenal, who admittedly no longer do so, and Spurs, who were runners-up in the league and runners-up in Europe in the last few years.

This is not Germany, France, Spain or Italy, where there’s often one giant club that wins most of the titles; albeit two in Spain (and very occasionally a third).

While the Premier League has its faults (too much negative play, long-ball rubbish and low-block boredom), it remains a fairly brutal and unforgiving league. It is a test of endurance and physical power. It is harder and faster than any other league, if not necessarily more skilful – albeit the fast football can also be beautiful and devastating.

It remains the league where aerial prowess is an outsized influence, even if not every team is “long-ball”; but even a “passing” side like Brighton came to Anfield with two 6’4″ defenders, plenty of other 6-footers, and a wide midfielder who was 6’7″. Pretty much every single Burnley played was 6ft and built like they were meant to play rugby instead, and spent the game jumping into the Liverpool defenders. These are often effective tactics for lower-table sides, but few of these managers could take a team and win a title. In Germany, teams would do so more by pressing, rather than with giants and long-ball football.

To defend the title without a crowd is a huge factor. Even Pep Guardiola acknowledged that a silent, empty Anfield was not going to help Liverpool when the Reds got back to 1-1 in the way it normally would. Instead, there was stoney silence. So far, this is the only season in the history of English football where, as proven in the stats, the away side is not at a disadvantage. As such, Liverpool have lost their home advantage.

The players are definitely struggling with the lack of fans at Anfield – that is unquestionable. There is none of the feel-good factor, and it seems that all they get by way of feedback is idiots on social media abusing them in every way possible, from the idiotic and unhelpful to the downright vile. There is none of the heartwarming support of the Kop.

These recent results back that up, and it’s clear the players are not enjoying the more passionless football of the Covid era.

It would logically suit the more sterile, more expensively assembled but still often brilliant machine-like Guardiola teams, and fair play to them for taking advantage.

With tons less money to spend (and having to sell key assets up to 2018 to fund big buys, before the on-pitch success became self-funding prior to Covid), Klopp made Liverpool the best team in the world and the 4th-best in the history of European football (based on Elo rankings) in part with the emotional fulmination of a heaving Anfield.

He arrived in 2015 to find a crowd that left after 83 minutes even if things were evenly poised. He turned them into a crowd that stayed until the games were won, even if it was in the 97th minute. That was no accident.

Liverpool have just lost three home league games in a row; but it’s still almost four years since they lost a league game in front of an Anfield crowd. Those contrasts speak volumes. The emotional football of Klopp is one of the things that sets him apart – his teams play great football, but with great spirit, allying the energy of passion with the ability to remain clear-headed and clever. The team right now, however, looks tired and dispirited, and there’s no 12th man to help.

Klopp never played to the crowd for whole 90 minutes, but he would tactically use it to produce a roar, if needed. That energy has gone. Anfield isn’t always like in the mythical Kop nights, but it can still be special.

Now there’s the club losing millions of pounds per game with no crowd, and the team losing 50,000 voices. It’s the worst of all worlds. Liverpool’s business model, and their football style, relied on these things: an expanded, packed Anfield, roaring the team on (and with some prawn brigaders filling the costly executive boxes, to help fund the team’s development).

All that money would go back into the team; now there’s a £100m shortfall, which in turn makes planning ahead more tricky (and may be behind the inability to improve the offer to Wijnaldum). And there’s a soulless silence every game, in the empty stands.

Simplistic conclusion: Klopp has taken Liverpool as far as he can

Let’s be clear: while Gary Neville was hugely unprofessional in saying that it was great that Liverpool were struggling (as part of the tiresome and increasing partisan “banter” with Jamie Carragher that, I feel, lets them both down), he did acknowledge that all great teams often hit a wall after three years of constant effort.

In fairness to Neville, he played in some absolutely great sides (almost as good as Liverpool last season, but not quite…), and they all did the same. They all hit a wall.

Unless your league is a cakewalk, you will always go a season too far, and after writing it off, need time to regroup in the summer to go again. In ultra-competitive environments, three years is often the limit, before a reset is required.

Man City didn’t rebuild after losing nine league matches last season, and failing in Europe yet again.

They simply got a couple of injured players fit again, added one or two new ones (just one regular starter in Ruben Dias), and once Liverpool fell apart this winter, they were freed of the pressure of chasing.

The psychological balance switched back in their favour; last season Liverpool’s form demoralised City. This season, when it fell apart after the Reds’ 7-0 win over Crystal Palace, it gave City a boost after their own iffy start to the season, perhaps not helped by bedding in a brand new centre-back, even if he now looks the real deal (foul on Mo Salah notwithstanding).

City didn’t sack Guardiola or make wholesale changes. I admit, I doubted whether Guardiola could turn things around when things looked stale earlier in the season on the back of last season’s woes, but he has. He’s building another team, but some of it was assembled with big teething problems last season.

I also said that Klopp rarely sees his squad lose belief, but of course, it can happen; what doesn’t happen is that they end up at war with each other and the manager (certainly that has never happened in his 20 years as a boss). You don’t get civil wars with Klopp.

In 2014/15 his Dortmund collapsed, due to injuries, their best players being picked off by Bayern, and bad luck / poor finishing. But they used the midseason break to get away, regroup, and came back refreshed, to rise from bottom to 7th, with top-three form. He couldn’t do that this season (and as he pointed out, he couldn’t cancel games at opportune moments, even if for legitimate reasons). Instead of having a midseason break, as had belatedly become part of the equation in England, it’s now an even more condensed season.

Klopp, along with Michael Edwards, addressed virtually every weakness from 2015, to create a perfectly rounded side.

They could play possession football, or longer passes; quick football and set-piece football – even fast throw-in football; counterattacking and slow buildups. They had pace, size, stamina, goals. It was a far cry from the team Klopp inherited, which was slow and small, and goal-shy, with a weak defence and an average goalkeeper.

I said back in 2015, both before he arrived and just after he arrived, that Liverpool needed two or three aerial giants (who could also play football – so not just giant lumps, aka Fellainis) as the Reds were terrible at set-pieces at both ends. Such rounded players are often very expensive, though, as the more rounded they are, the greater the cost, unless you can find a bargain or a free transfer. Big, fast, strong and skilful usually equals a hefty fee.

They did so, with Matip, van Dijk, Fabinho and Alisson (while Joe Gomez, with age and experience, got better in the air, and was no midget at 6’2″).

Then, smaller players, if elite, could be “carried” through the physical battles. Other smaller players (Joe Allen, Jordon Ibe, Alberto Moreno, et al), who were not elite, could be upgraded upon. In came 5’9-ers in Salah and Mané, and now Thiago. Robertson was no giant at 5’10”, but better in the air, and inches taller than the tiny Moreno.

Mid-sized players could get free at corners if the big guns didn’t score. As I keep saying, some weeks we’d see three men wrestle van Dijk to the ground, and while I was screaming for clear penalties that were never given, even with VAR, it showed how much space others could find. Other times van Dijk headed into the net or got an assist; or the ball broke for someone to score.

Liverpool went from the worst at winning aerial duels and set-pieces in the Premier League to the best. No more could teams of giants bully the Reds.

More recently, City followed suit. They added size to their defensive triangle in 2020 and 2021, and Rodri has adapted after a year, as has Cancelo; both over 6ft tall, like Dias and Stones.

City were vulnerable all last season as they played small defenders, and often didn’t use 6’2″ John Stones when he was fit. Now they have Stones, Dias (6’2″ and very physically strong), Cancelo (6ft) and Rodri (6’3″) to help them be less easily bullied in open play and, in particular, at set-pieces. They also added Ferran Torres, a 6ft attacker. They haven’t got rid of all the little tricky buggers, but those guys now have some protection, and you can’t set-piece your way to victory over them like you could in the past. Some of the aerial power they lost when losing Vincent Kompany has been restored.

Other players, like İlkay Gündoğan (aged 30!), have gone up a few levels after several years as squad players, while Bernardo Silva is back in the team after a poor 2019/20, when some may have said he needed to be sold. It all comes and goes. Gündoğan was always an excellent player, but only now, five years in, is he running the show, and has quadrupled his goals-per-game ratio. Sometimes the solutions are already in your squad, but the impact may not be instantaneous. Some players are slow-burners, or just need the right opportunity at the right time. Some may just fizzle out.

While City have become better at dealing with set-pieces, Liverpool have gone from the best overall set-piece team in 2019/20 to one of the worst. Indeed, the fact that the Reds don’t rank bottom is due to the goals scored before the set-piece scorers and defenders got injured.

In 13 league games without both van Dijk and Matip, the Reds have scored just one set-piece goal: Firmino’s header to beat Spurs. (Liverpool scored two on the opening day, with van Dijk netting one of them.)

The delivery against Spurs was perfect, 6’5″ Rhys Williams was standing next to Firmino, Jordan Henderson blocked off a tall marker, and the header was a kind of perfection of timing and accuracy you rarely see, as it wasn’t an easy chance. Everything had to be just right. But in the other games, it’s been attacking football that wins maybe a dozen corners, all of which are easily cleared.

Even brilliant delivery, as you often get from the Reds’ full-backs at set-pieces, will now only find a teammate very occasionally, if those teammates are small and outnumbered by bigger players. You can have a great leap, but if an opponent who is 6’4″ has an equally great leap, you won’t win the headers. (As I showed in 2015, aerial duel success rate increases in line with every inch taller a player is. The players who win 80% of their headers – the elite range – are almost always 6’4″ or over.)

People can talk about the number of extra passes Liverpool are now making with Thiago in the side, but to go from getting around 20 league goals from set-pieces (which might win 5-6 games, maybe more, that might otherwise have been drawn or lost), the Reds, without two of the top 10 aerial players in the league – two who can win 80% of their headers – are averaging a pro rata tally of just three all season. That’s a monumental drop-off. Beyond all the vague statistics, that’s a stunner. And it’s not even like Liverpool are going close with numerous corners right now.

Liverpool were never a set-piece team, because they had, and still have, super-high possession levels too. But they could both defend and score from set-pieces at an elite level. That is the biggest change; not the increase in passes.

Of late this season it’s been like the team Klopp inherited: averaging under 5’10” in height in many games, losing against the lower-table sides who just happen to average over 6’0, or even over 6’1″ in Brighton’s case.

Burnley won a penalty from an up-and-under in part due to Ashley Barnes wresting Fabinho all game (and conning the ref into booking the Brazilian just before half-time), and Brighton scored via a 6’7″ guy obliterating Trent Alexander-Arnold in the air.

You lose your sense of belief at your own corners, and you feel you have a glass jaw when defending them; you can grow anxious about just conceding them, and stop playing your natural relaxed game. Brighton and Burnley had too many players who could not be marked at set-pieces, while the Reds had too few who could do damage at the other end.

I keep pointing out that it’s like the team Klopp inherited, as so many of the players added to make major improvements – to add the pace and the height and the power – have been the ones out injured.

Teams know Liverpool can’t hurt them from set-pieces. Liverpool know they can’t hurt teams from set-pieces. Teams know they can hurt Liverpool from set-pieces, and Liverpool know they can be hurt from set-pieces. It’s all part of the psychological damage that you cannot get around by being a short team (unless you have a team full of absolute geniuses, and that’s only really be done in Spain). It all feeds into a sense of dread. If we can feel it as fans, you know the players can feel it.

Set-piece situations are traditionally responsible for a third of all goals scored in football, which is a huge proportion given that maybe only 5-10% of a game is spent (at a guess) defending or attacking set-pieces. If all the attacks that end up as corners essentially become goal-kicks (as the keeper just catches the ball), then you are losing so much of a cutting edge, even without changing your strikers (who often provide the “sense” of a cutting edge).

In other words, Liverpool, now with almost no set-piece ability in the air, could be expected to “lose” a third of the goals they would otherwise score, and to concede more than they otherwise might. Again, all the focus on the lack of goals I’ve seen has rarely covered the set-piece angle.

(I think Liverpool’s last set-piece goal was Salah’s header against Palace, when Matip won a towering headed assist. As I said, Firmino’s against Spurs was the only set-piece goal when Liverpool have been without both van Dijk and Matip, and the goal-rate had already dropped when it was just Matip without van Dijk. And of course, van Dijk offered the 5+ goals that some midfielders couldn’t even offer, in addition to two the injuries to two goalscoring midfielders in Oxlade-Chamberlain and Keita.)

Right now there’s not even any training time to work on maybe getting a few extra percent out of players who are never going to be the best in the air. Because you can improve in the air – Firmino is generally a better set-piece defender now than when Klopp took charge. But he’s 5’11”, and won’t be able to cope with a giant if that giant gets a good leap.

These lower-table clubs win games by constantly battering you in the air. You want to play on the deck, they want it in the air. They make it a fight, break up the game; and they may have one super-quick player who nips in when you’re all befuddled. They did it to City last season, and they’re doing it to Liverpool now. The aerial balls can be the jabs, the one quick run the knockout blow.

It’s not sophisticated but it’s often effective. If you also lack pace at the back, as Liverpool do now and as City did last season (when pairing Nicolas Otamendi and Fernandinho), it’s a constant vulnerability. It’s hard to be at your best on the ball if you feel weaker at the bck.

With van Dijk and Matip, even the ultimate street-fighting boxer’s-build footballer in Troy Deeney admitted you just couldn’t get at those guys. He obviously knew he could get at Dejan Lovren (tall, but averaged around 60-65% of aerial duels won, so well below the usual levels of van Dijk and Matip), and before him, the more skittish Martin Skrtel.

Until this season, teams were often beaten by Liverpool in the tunnel, looking at the size of Klopp’s men, as well as thinking about the skill, pace, the insane pressing energy, and their warrior-like belief. They’d clearly dread playing them. Players admitted it. But now, they can sense a weakness, because it’s a team shorn of several dimensions. It’s not as tall, not as fast and not as full of energy.

The fastest players and elite aerial-duellers have been taken from the defence. Pace and goals have been taken from the attack and the midfield. Energy has been taken from everyone.

Size and heft has been taken from the midfield to cope with the defensive injuries, and so we’re back to the conundrum of whether established midfielders are better there in the short term, or to go for the new guys who may be totally out of synch with the rest of the team, and not initially up to the pace and chaos of the Premier League (but who might be amongst the few new defenders who settle quickly).

In time these guys should settle, then improve, but it’s not easy to join a club as a centre-back in January; there’s no time to do six weeks of preseason, no time to learn about the shape or to synchronise movements as a back four. With a game every three days, there’s not even time to do much training at all – it’s all just travel days, match days and recovery days.

Nemanja Vidic was a bit of a disaster when he arrived at Manchester United mid-season, but six months later he was a totally different player. He ended up being one of the best of the Premier League era.

Even van Dijk, £75m of insanely good footballer with lots of Premier League experience, started his league form with a 1-0 defeat at Swansea, with the Reds going into the game on the back of an 18-game unbeaten streak. Soon after he conceded a penalty in a home draw with Spurs. It was one of six games (excluding another in the FA Cup) where the Reds conceded between two and four goals between January and May. You could see his class early on, but the defending wasn’t perfect.

Simplistic conclusion: Liverpool need an overhaul and/or to buy a load of players

None of what I am saying here (congratulations, you’re three-quarters of the way through!) means that next season will automatically be hunky-dory, because new problems can always arise. Mo Salah may do a Coutinho and go on strike to move to Real Madrid; Sadio Mané may suffer some terrible injury; Virgil van Dijk may have his other knee snapped by Jordan Pickford.

But if the crowds are back, the key players are fit, there’s a proper Kloppian preseason (super-tough, to build the stamina to press), and if the five new players from this season continue to adapt, it would surely be a lot more like the Liverpool of 2017-2020 than the one that has been poorer in the entire Covid-19 era.

Indeed, Covid-19 arrived too late to scupper Liverpool’s title bid, but it has made life harder, without doubt.

Remember, with every injury (especially to your most effective players), not only does the team get weakened, but the bench does too. A good player goes from the bench into the XI, and a fringe player comes into the 18 or 20. Short-term you can muddle by; longer-term you will revert to the reduced mean.

For Liverpool to have van Dijk, Gomez, Matip (at least for some of the time), Keita (ditto), Jota and others back next season would be like spending £250m on players who, if fit, will be like perfect new signings who don’t need time to settle. They won’t need to adapt to English football, or Klopp’s tactics, or each other as friends and trusting teammates. They’ll know the pressure of the heavy shirt. It’s a football cliché, but it’s true: they’ll be like new signings.

As long as they can overcome their injuries with no lingering damage, they will bring back the qualities the Reds have missed. (Again, there may be new injuries, as there almost always are; but it’s the quantity and the clustering that has been the killer this season.)

Even to just have Matip and Keita fit for half the games would make the squad that much stronger for those matches. To have van Dijk and Gomez back would be huge, and of course, Jota being back this season will be a big bonus – albeit he will surely return rusty having not even trained for months, with his knee in a brace until very recently.

No one is too old, even for next season. Only James Milner is over 31, and he is like Benjamin Button. (He’s also not a first-choice player.)

The team as a whole will not be too old, although it will obviously need freshening up very gradually over the coming years.

That said, that process has already started. Of this season’s five first-team squad signings, all bar Thiago, who isn’t over the hill at 29, are a good age; and if he is signed permanently, Kabak, aged just 20, has the potential to be a world-beater. He could be one of the rare centre-backs under the age of 25 who proves world-class, but even the jump in progress from ages 20 to 23, in any position, is often huge. (My own rule of thumb is that goalscorers who don’t rely on pace often hit a sweet spot where it all clicks at age 22/23, and for centre-backs it’s 25/26; having pace often speeds up the process by a year or two.)

Curtis Jones will be a year older and better, and the five new players signed in 2020/21 will have had time to settle, even if means playing in losing teams for the time being – a bit like Henderson in 2011/12, getting slated for being rubbish at right-midfield in a side that didn’t win many league games. It’s all a good education, even in defeat or bad seasons; just as Phil Foden spent four years learning in the City squad (with years of hype and little playing time initially), increasing his minutes with each campaign, until finally staking a claim as a first-choice in 2020/21.

We can see if Kabak adapts now, or if he shows promise but comes good next season. At 20 his potential is huge, but it’s a big learning curve: in terms of his all-round game and in learning about the league. You can’t skip it, and it’s hard to find signings who settle immediately, at any age. Yes, the instant successes do happen, but a great many new buys need time to adjust.

The worries for next season would obviously include Wijnaldum leaving, but Liverpool are overstocked in midfield, in part because the defensive midfielders cover as centre-backs and the attacking midfielders cover as wide attackers. I love Gini to bits, and he’s one of the players who never seems to get injured, but I wouldn’t begrudge him a move to Barcelona if that’s where his heart is. (If he moves to a Premier League rival, that’s another matter!)

I actually think Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain has been terribly hamstrung since injury – he’s returned with zero touch and flow, and as a player who could add pace and goals has often been a passenger in his few outings (mostly giving the ball away with the rustiness of someone who hadn’t played since the summer, but also as a player whose touch can be very good but vanishes when low on confidence). He’s not the player he could be after a proper preseason and not coming off the back of a long time out.

The same applies to Keita, and I would appoint a special physio just to try and help him overcome his niggling muscle issues. I wouldn’t write him off, as he’s too good, and some players do overcome their muscle issues (although others don’t; it’s hard to tell who will and who will not).

Thiago should be better next season without the impact injuries and settling-in issues (and with Henderson and/or Fabinho alongside him as protection). He’ll be 30, and still in his prime.

Liverpool obviously need Alisson to bounce back, and for him not to do a Dudek/James/Mignolet and lose his mojo for good after too many errors. Once keepers start to look vulnerable it can be a slippery slope.

Even David Gea, the best keeper for most of the decade until Alisson arrived, has largely crumbled in the last couple of years, once mistakes became a mental scar.

Alisson has got over mistakes before, but this was a particularly bad game, for reasons that may have been beyond his normal control. He had one of the weirdest few minutes I’ve ever seen from a keeper, and even the fourth goal was one he would otherwise expect to save, as if his reflexes were dulled. If he was impaired, then that can explain a lot, even if it’s only to himself, to help bolster his belief.

While I think the top four remains very much attainable, I don’t think there’d be a mass exodus if Liverpool didn’t achieve that. I actually think that if Salah wanted away, the money could be used the same as with Coutinho leaving, to make the team and squad better.

(Not that I’m saying Salah should be sold, but he’s probably the most saleable asset and will soon be 29. He’s got a great goals return this season, albeit a third have been from the penalty spot, in a rare season of quite a few penalties for the Reds – albeit bizarrely, they’ve conceded more than they’ve been awarded; half of which were poor or debatable decisions, and half of which even I admit were stonewallers.)

The Reds got two of the best teenagers in Britain in Harvey Elliott and the newly-acquired Kaide Gordon from Derby, for whom he had already played at the age of 16. As noted, it took Phil Foden four seasons of increasing minutes to get this good aged 20 – the frequent pattern for most young players, in an era where very few become regulars at 17.

Those kids could start adding minutes next season. Elliott is particularly prodigious, with a game intelligence and passing vision rare for a 17-year-old, allied to the sturdy physique of a scrawny kid who has suddenly turned into a man, albeit not a very tall man. Foden, while special, was arguably no better than they are at the same age.

We can’t bank on these players, but if both Elliott and Gordon were playing in the Reds’ U18s this season they would be absolutely tearing it up. As it is, Elliott is excelling as the youngest player in the Championship, which is far stronger than U18 football, and far stronger than U23 football. He’s nearly ready, it seems, to at least be on the bench for the Reds. While other Liverpool players have done well on loan at that level, none has been anywhere near as young as this. Elliott is special, and at just 17 has plenty of scope to improve.

Of course, Rhian Brewster was nearly ready at 17, then missed two years with injury, and as such, lost a ton of development time. Given the chance to be in Liverpool’s squad this season he instead chose to play regular football, only to end up a sub at the bottom club. That’s how it goes. He can be bought back if it clicks for him, and I wouldn’t write him off, as he has something about him – if this season doesn’t break him it’ll make him stronger. But it’s a dilemma when young players get too impatient.

Of course, maybe only 25% of the best 16/17-year-olds go on to become world-beaters. The best players I saw in many years in the 2000s watching the Reds’ U18s games included Raheem Sterling, Daniel Sturridge (for Man City) and Jack Wilshire (Arsenal). Obviously Wayne Rooney bypassed all that, aged 16. Michael Owen, going back a bit further, looked a star at 15, and while all these players became elite, some were washed up early due to injuries.

Why do the other 75% (as a guesstimate) fail to even make the grade to start with and drift away? Some get seriously injured. Some don’t develop physically – they remain too small, or they don’t become strong enough or fast enough. Some lose their way, once they become famous before they’ve even made a senior appearance, and fall foul of hangers-on and groupies, as they sign big-money deals; or, perhaps less common these days, start drinking too much alcohol and other vices. Some stop training at an elite level, as if they’ve made it, and now they can lean back and reap the rewards – when you have to train as hard as ever just to stay at the level you’ve reached. Some get depressed and disillusioned, as happened with Jordon Ibe.

Indeed, sometimes when you achieve your dreams in life you become depressed, as if a part of you – the motivating drive – has died.

Olympic gold medal-winners can go through a mini depression, and maybe Liverpool are feeling that right now, having lost the great dream of ending 30 years of title drought, whilst in the limbo of still having not celebrated it properly with the fans.

Sometimes you need to go away and refocus. Sometimes it just needs a reset, just as sometimes a team needs to get in at half-time (Istanbul being the best ever example), or a team needs to end one game, draw a line under it, and come back stronger, with a clean slate, in the next game. (And if you’re struggling to enjoy your football, being thousands of miles away from family during a pandemic won’t be easy, at any age.)

The Premier League is full of players who were outstanding at 17, but often doing so in leagues all over the world. It’s also full of those who were merely good at 17, and worked harder and harder and harder. Some were non-league players at 17; outcasts, dismissed from academies, but full of burning ambition.

But if you have elite 16/17-year-olds who train brilliantly (like Elliott and Gordon, by all accounts) and who remain hungry, you can really go places. Again, it also needs luck; injuries can turn great prospects into merely decent players. And it’s never easy to integrate young players; often they are introduced in transitional seasons, albeit occasionally one might get regular minutes in a title-winning team if they can be helped along by the senior pros.

Almost the end! … of the article, not Liverpool or Klopp

As someone who backed Klopp when people doubted him in October 2017, when his record was identical to that of Brendan Rodgers, I see no reason to doubt him or the team now. Even if this season gets worse (as might happen), I have total belief in his ability to have things be much better next season, luck permitting.

While I have been critical of some of the players’ decision-making this season (such as Salah refusing to use his right foot week after week, until he recently used it again to great effect and the goals returned), and pointed out the poor individual form or tiredness of several stars, this remains a supremely balanced squad, full of experience, pace, height and, if able to have a proper preseason, stamina. But that’s based on everyone being fit, and a normal summer.

Again, as another contrast, if Man City had lost Dias, Stones and Laporte for the season before the halfway point, and relied on midfielders and kids to fill in, they would not be running away with the league. If they had several other injuries, their chances would get slimmer still. Yet when everyone is fit they have a great squad, and like most teams, they can usually carry a couple of absentees, even if top players. That said, having just one injured defender last season hampered them (albeit with Kompany having also departed).

Perhaps Liverpool will have to evolve and adapt a little, come up with slightly new ways to attack and defend – football teams are always evolving – but when a team has done what they did for three years, and when other great players are added (and very few have left or are melting), then it’s likely that this is a hit-the-wall season (beset by injuries), rather than a sign that a complete rebuild is required, even if that’s always the knee-jerk reaction.

Reset? Yes, and the summer can’t come quickly enough. Rebuild? No, not at all necessary.

Postscript, Wednesday 10th February

Since publishing this piece, which was written in one sitting on Monday (fuelled by adrenaline and caffeine, before I spent the next 48 hours feeling like I needed ice baths and stretches), I’ve seen a few good bits of information that further bolster my arguments, or which add a new dimension.

(If 12,000 words were still not enough for you, here’s 1,500 more.)

Obviously, and tragically, news has just been released that Jürgen Klopp’s mother has died, and rumours (in January) of her death were said to be behind his more depressed demeanour of late – it’s bad enough having a loved one be ill and die during a global pandemic, and even worse to be miles away and barred from attending the subsequent funeral due to flight restrictions. Unlike his father, at least his mother lived to see Klopp conquer the whole world.

But this is a very sad time, and it puts into context the difficulty of anyone in football working abroad, miles from their families. Just as life is tougher for almost everyone right now, it’s tougher for footballers and football managers too, as even money and fame do not solve all your problems, or alleviate the loneliness that can arise. Different people have different advantages in life, but there is no such thing as privilege when it comes to tragedy, grief, pain, illness and depression.

Anyway, in relation to the Reds’ struggles this season, the analysis from Monday Night Football is well worth watching:

#MNF analysis of Liverpool’s players minutes & appearances since the 2018 CL final!

— Jamie Carragher (@Carra23) February 8, 2021

In contrast to Roy Keane’s unhinged ranting, this is a good use of a data by Jamie Carragher and Sky (and some fair comments by Chris Coleman), and shows how hard Liverpool’s core players have been pushing for over two and a half seasons (and some of them were pushing hard before then, too).

It shows the particular strain Andy Robertson has been under. Of course, Kostas Tsimikas was bought to ease that pressure, but he’s missed a lot of the season. No one noted him as being a big loss, when he was out for months, because he’s yet to really get a game – but his purpose, as well as to challenge for the position, was to keep Robertson fresher. No wonder Robertson looks knackered.

While Jamie Carragher makes many good points, he also says Liverpool need new players in certain positions: a centre-back, a replacement for Wijnaldum, and a striker.

I would argue that Diogo Jota and Thiago, whom he doesn’t mention, are part of the move forward, with the centre-back solution he says is required also already at the club in Ozan Kabak (although he does say that Kabak might prove the solution; obviously we don’t know how that will pan out, but the potential is there).

Adding too many new players can be as troublesome as not adding enough. Liverpool won the title without adding a single first-team player, and the Reds must not throw out the shared understanding on a whim.

Given the time it can take new players to settle (often a season), and young players to develop, this is a good chance to integrate Thiago, Jota, Tsimikas, Kabak, Davies and, of course, Curtis Jones. Pain now can equal gain later.

So unlike Carragher, I don’t necessarily see a need to rebuild or invest big money, as I made clear in this piece – and with the club losing a ton of money every week, it may not be possible to even think about any big buys until Covid-19 is fully under control; and with new variants arising that may take longer than expected.

(Hence my suggestion that selling Salah might be one solution, even if it’s not a solution I’m saying I’m eager to see – I’m simply suggesting that it might prove a good time to sell a super-high-value player just as he turns 29, so that, as Bob Paisley used to say, he loses his legs on someone else’s pitch; and by losing his legs, that’s not to be taken literally, as a lot more people seem to take metaphors literally these days… At the same time, if he’s happy to stay at Liverpool and the club want to keep him and build around him, that’s great too. While certain players can remain hugely effective at 33/34 and beyond, they are still often the exception; and so some change to a forward line all hitting 30 around the same time might be required – albeit Jota could nail down a place next season. My sense is that Mané is still improving, and I think Firmino, as a clever player who doesn’t rely on pace, can remain part of the attacking equation – albeit I still believe there’s a potential role back in his old position of attacking midfielder. While there’s no one single 29/30-year-old Liverpool player I’d want to see go, if one were to join Wijnaldum in leaving, it would at least allow the average age to be lowered a little.)

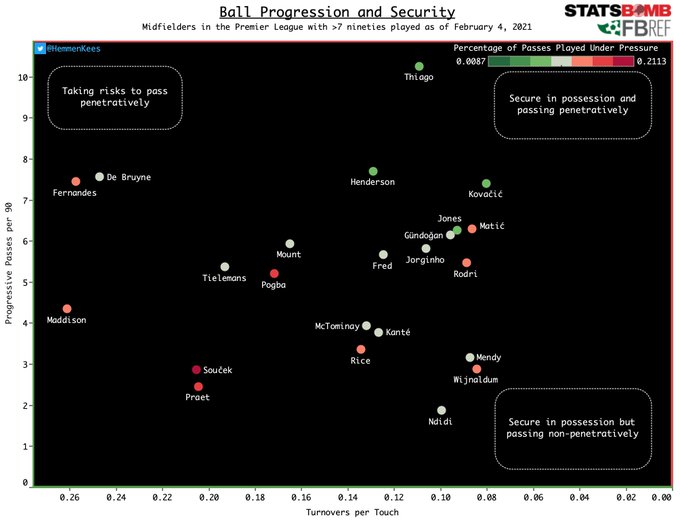

Since writing the piece on Monday I discovered this graphic (below), which shows that, rather than slow Liverpool down, Thiago does quite the opposite. I’ll include a jpeg of the image, as well as imbedding the tweet:

Here’s a version of this contextualized for pressure https://t.co/p0lsvIHtQl pic.twitter.com/nBx5e9kwjc

— Kees van Hemmen (@HemmenKees) February 10, 2021

While his passes are not played under as much pressure as some others on the chart, he is in a zone all on his own on the graph, as he attempts more progressive passes than any other Premier League midfielder – with a healthy mix of recycling possession along with those ambitious passes. Liverpool had games last season where they made over 900 passes, so I think it’s wrong to focus on how often the Reds pass the ball since Thiago has come into the side, not least because it varies with game-state.

At times, last season and this, Liverpool’s possession was slower in the first half of games, as they sought to control the early stages (in contrast to the blitzing of the earlier Klopp years), then grew more dynamic after the break.

I’m not pretending that Thiago has been utterly flawless, and his tackling still remains an issue, but even with my eyes, closely watching him game after game – and thus before seeing the chart – I felt the notion that he slows Liverpool down to be flawed thinking.

If the data had shown me to be wrong, then I’d admit that; but instead it just backs up my assertion from Monday, and before. This is a player still yet to play in anything close to resembling Liverpool’s best side (bar ten minutes of the game at Everton until Virgil van Dijk went off injured, in what was Thiago’s only start for many months due to suffering to his own knee-crushing assault), and any understandings he builds up in the next six months can be taken into next season, along with an adjustment to when he can and cannot tackle in the Premier League.

On the topic of injuries, TTT subscriber Lubo shared the following comment, which again backs up my assertion – albeit my assertion was based largely on empirical evidence, logic and reasoning (the further down the pecking order you are forced to go, the logically weaker the solutions will be) and not any actual data or academic studies:

“A point on the injuries to Gomez and Matip on top of that of Virgil. Ryan O’Hanlon writes an email newsletter and in his latest one, on Liverpool (he is a fan), he mentioned a study of NFL teams that looked at defenses and found out that it’s not an injury to you your first-stringer (top defender) that kills you, it’s the injury to the second and third backs ups that sink you, as that means you now have to play your fourth and fifth options and those are just never that good. Had Gomez and Matip stayed fit and healthy, and allowed us to play Fab and Hendo in midfield more often, it would be a completely different story. Alas. Here is a link to the study, btw, though it is paywalled.

I’ve also seen the example of how Roy Keane’s Man United crumbled after Rio Ferdinand was suspended for failing to attend a drugs’ test, winning just four in a run of 13 league games to throw away the title in 2003/04 (and they also did so in 1997/98), so Keane seems to have an incredibly short memory, as well as a short fuse.