By Bob Pearce.

Introduction.

I’ve been working on a large writing project for a few months now, looking at how we see, think, talk and act. It feels like some of these chapters may be relevant at this moment time.

Pretty confused, huh?

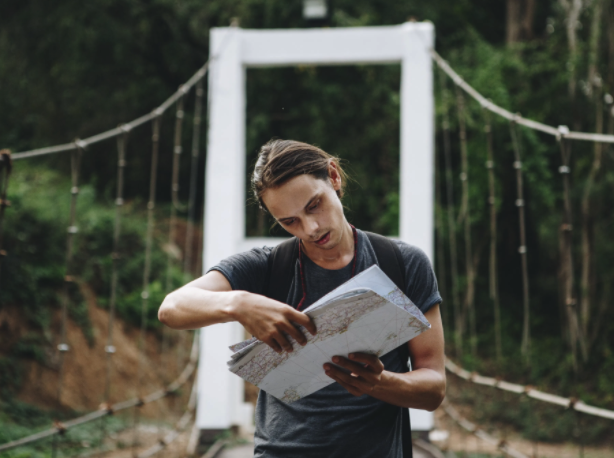

Picture yourself going somewhere that you have not been before.

You may be worried that you could get lost.

So you decide to get yourself a map.

Stop and think about how this map can help you.

A map of this somewhere-you-haven’t-been-before will show how different and unfamiliar things and places fit together in a way that makes sense. It will give you some reassurance by removing some of your worry. It extracts some unexpectedness and plants some predictableness. It will help you see what to expect next.

A map will be using someone else’s experience to help you to plan ahead and take your next step in a town called ‘Unfamiliarity’. Instead of being limited to your own ‘knowledge’, and instead of having to discover what others have already discovered, and instead of re-learning what others have learned, you can now carry on where they left off. This means that, once you have your map, you don’t actually have to be in ‘Somewhere New’ to begin exploring. You can ‘walk’ around this picture that represents that place.

Now picture yourself going somewhere that you have been many times before. You won’t be worried that you could get lost. You have no need to carry someone else’s map. It will be enough to have memorised a map in your brain, learned and built from your own experience. Again, you don’t actually have to be in this place named ‘Familiarity’ to go searching. You can ‘wander’ around in your brain map.

If we were to judge a map by one question, that one question would not be ‘Will it be a complete and accurate map?’ It seems highly unlikely that any map has ever been ‘perfect’. Just try to imagine a map with-every-tiniest-itty-bitty nitty-gritty-detail. Think about how overwhelming that would be. It’s completeness and complexity would be very nearly as confusing as having no map.

Maps shrink an ever-changing place into a smaller never-changing place, and to get a 4D world into a 2D map will mean losing 2 of them there Ds. All maps, including those in our heads, will be a compromise of what we want to show and what we can fit in. A world map will have less space to include infinite information, so they stick to oceans, borders and capitals. And although a town map may show more than a world map, it will still be incomplete. They both overlook details to reveal a simpler picture.

So all maps will be a distortion. They don’t just show and tell, they also hide and hush. All maps ignore plenty and leave a whole lot of different things out. To find our way around we don’t want to include a whole mess of too-much-going-on. To prevent important details getting over-shadowed and lost, maps will be selective of some of everything and rejective of most of everything. They will be intolerant of irrelevant information and deliberately disregard and discard distracting details. They sift through a confusing messy ‘noise’ to pick out a ‘tune’. We need what we need and anything else can be dropped. Maps clear clutter to create clarity. If it distracts you ditch it. To create a convenient simplified picture, a map will be as much about what you leave out as what you allow in. All maps always remain incomplete and unfinished. They’re supposed to be.

You could say that maps only work when they don’t tell the whole story. It helps you see what you need to see and ignore what you don’t. An incomplete adequate map, emphasising what’s relevant and erasing what’s irrelevant, will be more helpful than an attempt at a completely accurate map. A map can look lavish and a map can seem scruffy. A simple and straightforward hand drawn map, made up of a few basic lines, labels and landmarks, sketched on a scrap of paper, can be enough. Any map will be a simplification and, as long as it helps us to confidently get between A and B it will be fine. We’re just making pictures here. It will do.

If our map will be adequate and a compromise rather than accurate and complete, what do we choose to include and exclude in our map to help us get between over here and over there? That depends on where we think we stand, where we want to get to, and how we want to get there. When we want a map for a specific purpose, what we want it to tell us, and not tell us, becomes clearer.

You could say that what we include in any maps that we choose to use, including our brain maps, tells everyone what we choose to count and discount to shape and guide our thinking in this situation. No map can be point-of-viewless. You’ll find no maps with an impartial perspective, looking out through a neutral nowhere. All maps stand somewhere and say it as they see it. This means that if someone else drew this map for us they will have decided what to include and exclude for us. As a map will always be selective it helps to check who was doing that selecting and if we trust their choice of selections and rejections.

If you were to judge a map by one question, you could ask ‘Is it the right map?’. That sounds like a tough question. Luckily, we don’t have to even attempt to answer it. If all maps remain partial and no map can be an impartial version of somewhere, how does it help us to talk about our going-out-of-date re-presentation of that place being ‘right’? Pretty confused, huh?

The rest of this article is for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]