If Liverpool hold onto their lead in the title race all the way through to May then, aside from Leicester’s improbable triumph in 2016, they would be the cheapest champions – by some distance – since Roman Abramovich changed English football. (The oligarch arrived in 2003 but it was 2004/05 when his spending coincided with a league title and contributed to the demise of Arsenal, then the best team in the land.)

And in relative terms, they would be the cheapest champions (aside from Leicester) since at least 1992, when, as we know, all records began.

Something all English people should be proud of – but of course, won’t! – is that the Reds are now ranked the 4th-best team in history according the long-established ClubElo rankings (based on all football results in history), just to sum up the incredible context of what the club is achieving.

Some may argue (wrongly) that what Liverpool are doing is in some way bad for English football, but becoming the best team in the world on roughly half the budget of Manchester City – and by spending far less on transfers than the title-winning sides of Chelsea and Manchester United since 2004 – is an incredible achievement.

Being smarter, and applying more attention to detail to make marginal gains, is a good thing. Buying undervalued players, often from relegated clubs, and making them world-class is a good thing. Finding little-known coaches – such as Pepijn Lijnders – and analytics staff, and having them make a world of difference is a good thing. A policy of only giving big wages to players who have already proved themselves at your own club is a good thing. Appointing a throw-in coach who has turned Liverpool from one of the worst at keeping possession from a throw-in to being the best is a good thing.

After all, anyone could have appointed Thomas Gronnemark, who was working with little Scandinavian side Midtjylland, and the Reds duly turned from a team that frequently gave the ball away at throw-ins (a bad idea) to one that now regularly score goals from the possession kept by smart fast throws (rather than long projectiles launched into the box that many of us expected when he was appointed). Yes, Liverpool have enough money to be competitive, but still lag well behind the Manchester clubs in terms of resources.

Plus, it turns out even bringing in Adrian on a free transfer was a good thing.

The problem is not a weakness with the English league, as it might have been in the past: Liverpool are European Champions, World Champions and have just had the best year in English football history if you marry league results to European success. (You can also throw in world success too, although we all know that’s not taken as seriously.) Liverpool are setting a whole host of all-time records in the past 12 months.

The English league is extremely competitive right now; the difference is that, based on results over a long period of time, Liverpool are now ranked above any other English side in history in the ClubElo rankings, going ahead of the 1961 Real Madrid team to now be behind only Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona, Pep Guardiola’s Bayern Munich and the Real Madrid side from 2014, all of whom were either by far the richest or 2nd-richest club in those countries. Liverpool are currently the 3rd-richest club in England on the metrics we use on this site.

(As these are the peak figures, Liverpool cannot now fall from 4th any time soon. That’s now a permanent high-water mark. They would need someone to overtake them, but obviously no one is even close right now, and a team like legendary Hungarians MTK Budapest in 1955 cannot do so on account of the players being dead, or in their nineties. And of course, Liverpool can still rise in the rankings, even if it seems unlikely that the form they are in can be flawlessly maintained – as it would need to be to rise further – for the remainder of the campaign; and, after all, the club only needs ‘top four’ form from now on to secure the title.)

ClubELO January 3rd 2020

| 1 | 2012-04-15 | 2107 | Pep Guardiola | |

| 2 | 2014-03-26 | 2104 | Pep Guardiola | |

| 3 | 2014-05-01 | 2096 | Carlo Ancelotti | |

| 4 | 2020-01-03 | 2070 | Jürgen Klopp | |

| 5 | 1961-03-19 | 2069 | Miguel Muñoz | |

| 6 | 1993-03-18 | 2052 | Fabio Capello | |

| 7 | 2019-09-01 | 2047 | Pep Guardiola | |

| 8 | 1955-10-20 | 2037 | Tibor Kemény | |

| 9 | 2008-10-23 | 2026 | Luiz Felipe Scolari | |

| 10 | 2008-05-12 | 2026 | Alex Ferguson |

.

You can argue that Liverpool need to win the league to cement that greatness, but this is still the Champions of Europe winning 31 league games in a calendar year (and going more than 12 months without defeat, as well as going the longest number of games by any club in English league history with just one defeat: a rolling figure of 58), whilst also beating Bayern Munich and Barcelona on the way to Madrid in June, topping their group this autumn/winter, and winning both the European Super Cup and the Club World Championship.

Yes, winning the league will indeed cement that greatness, but even before then, the club has reached two Champions League finals, finished with the 3rd-best ever points tally in English football history and are one win away from the best start to a season in English football history, whilst currently on course for a 110-point finish (even if that total is unlikely to be reached). As I pointed out in the summer, no team in history has ever had as good a league season (in terms of points and wins in leagues with more than 34 games) concurrent with winning the Champions League/European Cup; and that, actually doing so at the same time is more of a sign of greatness than winning the domestic league and then having a mediocre defence of that title whilst winning the European Cup.

While I didn’t expect Liverpool to get some kind of special award when I pointed this out last summer, my focus was on the fact that this team was perhaps even more special than people were realising. All the subsequent evidence bears out my conclusion.

Spending

And yet it’s all been done on a fraction of the budget of some other clubs. I’ve spoken for years about how gross spend is a terrible argument, and that net spend – while better than gross spend – is flawed for several reasons, not least the random start and end points, and also, the saleability of players at any given point in time. That said, ESPN recently published the net spend of clubs since Pep Guardiola arrived in England, and by using Transfermarkt’s figures, Man City were at £527.8m since 2016, Man United at £432.3m and Liverpool miles behind at £75.3m, a mere fraction of a net spend.

Now, obviously Liverpool received up to £142m for the sale of Philippe Coutinho, so that affects the net spend. But of course, Coutinho was seen by many as the Reds’ best player, and there was no little unease at his departure. What about if Man City had been forced to sell Raheem Sterling or Sergio Agüero? (Indeed, City plucked what was looking like the carcass of Liverpool FC as recently as 2015 to land Sterling, as the Reds – prior to the arrival of Jürgen Klopp – looked about as far from title winners as they’d ever been.)

So there was a huge risk involved in offloading a key asset in Coutinho, but that money paid for Virgil van Dijk and Alisson Becker, with £1m in spare change. The difference with Liverpool – as seen in the cases of Fernando Torres, Luis Suarez, Sterling and others – is that, unlike Man City, Man United and Chelsea, they often had to sell their best players. In the past decade, City have never had to sell anyone. Only now, in 2020, are Liverpool in a secure enough position – financially and in terms of on-field success, as part of a gradual building process with success providing the money to compete – to hold onto their main assets.

Ten years ago Graeme Riley and I embarked on the Transfer Price Index project, creating an index of all Premier League transfers each season, and working out Premier League inflation (which runs much faster than standard inflation, at around 25x the speed), and from this we could work out how much each team cost in current day money, enabling us to compare across eras using the same benchmarks.

Until 2010 there was no way to accurately map transfer spending against success; not least because some seasons – like Liverpool this season, for example – a club may actually make a profit on transfers. While the Reds are c.£30m in the black on deals in 2019/20, they also didn’t have to give up van Dijk, Alisson, Mo Salah, Roberto Firmino, Sadio Mané, Jordan Henderson, Naby Keita, et al, who have been assembled as a squad over a nine-year period.

(Incidentally, a big net spend doesn’t correlate with success in any given season, but it does tend to make it more possible a further season down the line. This is why I argued on several occasions last summer that Liverpool did not need to spend any money, given the age of the squad, the growing cohesion, and the lack of any gaping holes in thee XI. As seen with someone like Fabinho, it actually took almost half a season before he could start affecting results in a positive manner, and that introducing new players can often see you suffer for a while, due to a lack of shared understanding; as has arguably been seen with Man City and Rodri this season, as the Spaniard struggled at times to adapt. And of course, a big net spend is pointless if you buy all the wrong players, or don’t have a plan to integrate them.)

So, actually, Liverpool would never be able to win the title based on their 2019/20 spend figure of c.-£30m, if you just judged the correlation between net transfer spending and success. Indeed, you might say that -£30m would be relegation spending.

The key is the sum of the outlay on squad assembly, when adjusted for inflation; and more important than the cost of the squad is how much of that talent makes it onto the pitch (you can blow your entire budget on five expensive players and if they’re all injured you won’t get any of their influence. That said, what tends to happen is that the richest clubs have the greater number of expensive signings, to absorb the shocks.)

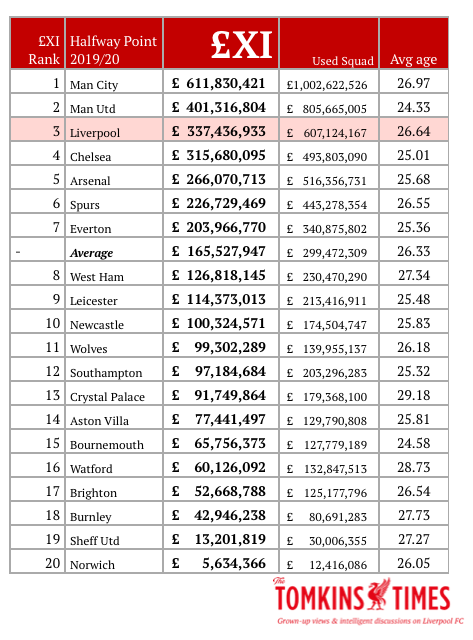

Before getting onto the relationship between spending and success, here are the £XIs for this season at the halfway point.

Then, you need elite coaching, preparation, tactics, and so on, to make the most of what’s at your disposal. But when you look at the cost of a team you can see clear correlations between spending and winning the title, with just the very occasional outlier.

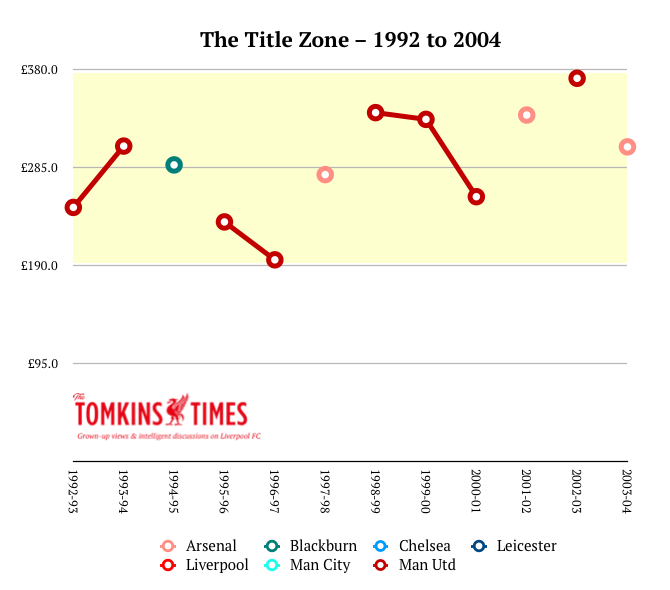

The Title Zone

Graeme and I called the average cost of a team over the course of 38 league games the £XI, and this closely correlates with success, as the following graphs will show. Because all teams can be compared in current day money we can look at clubs side by side. (We didn’t go back beyond 1992 due to the size of the undertaking in gathering the data, and while our data has been used in academic papers and by a European commission on transfers, we only do it as a side project – it’s not something we seek to monetise or prioritise.) Every year we update the figures and so currently we are using “2019 money”.

In the past I’ve talked about The Title Zone, and it gets even more interesting in 2020.

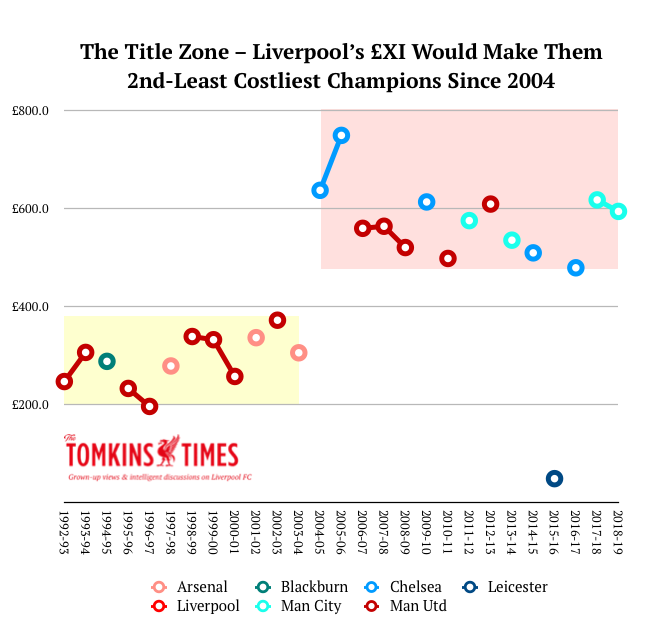

Up until 2004 the title was won by a club that had an £XI between £200m and £400m. So, even from 1992 to 2004 – pre Abramovich domination – there was a clear “Title Zone”.

Blackburn, for instance, fell somewhere in the middle: nearly £300m in 1995 when they won the title. So, in 1992/93, for example, there was Norwich, finishing 3rd, and QPR, in 5th, with £XIs that cost about one-fifth of the eventual winners, Man United – but obviously they did not win the league. Having a good season and winning the league are two entirely different things.

Even runners-up, Aston Villa, had an £XI that was 76% the cost of United’s, which put them in the Title Zone too. (QPR’s was only 19% the cost of United’s.)

The difference between the pre- and post-Abramovich Premier League is the number of clubs at the level of the Title Zone. The qualification figure rose markedly – and therefore the number of clubs able to field an £XI that can enter that hallowed zone fell dramatically.

At various points in the decade between1992-2002, the clubs who had £XIs in the Title Zone for at least one season were Liverpool, Blackburn, Spurs, Newcastle, Arsenal, Aston Villa, Everton, Leeds United and obviously Manchester United; and so, theoretically, all were in with a chance of winning the title – and quite a few at least made title challenges. (Albeit Everton, Villa and Spurs only briefly had that kind of £XI, and never was it at the upper end of the limit.)

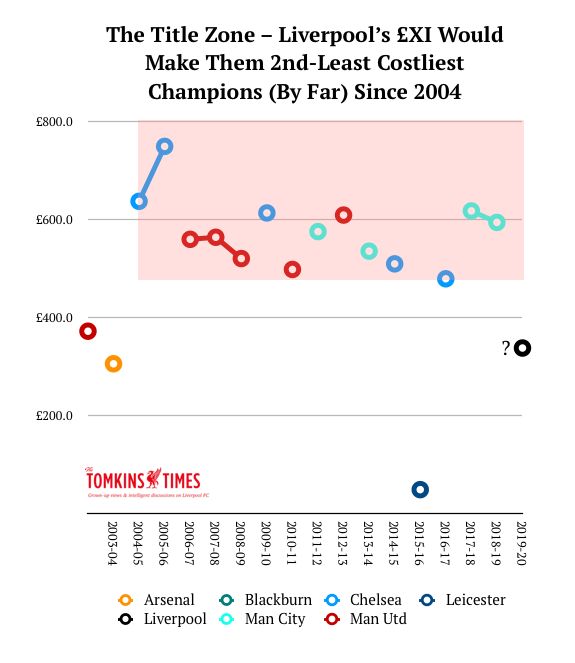

In the past 15 years, the only clubs to have an £XI in the Title Zone are Man United, Chelsea and Man City. So, excluding the occasional outlier, we could say – based on £XI – that the only clubs who stood a chance of winning the title between 2005 and 2019 were Man United, Chelsea and Man City. And who won the titles? – in order: Chelsea, Chelsea, Man United, Man United, Man United, Chelsea, Man United, Man City, Man United, Man City, Chelsea, Leicester*, Chelsea, Man City and Man City.

(* Yeah, it still makes no sense.)

So, from nine clubs in The Title Zone in the first decade of the Premier League to just three in the next 15 years. This has been the problem with English football; not Liverpool’s recent rise to greatness, which exists outside the Title Zone.

Neither Leicester in 2016 nor Liverpool this season are anywhere near the Title Zone, albeit the Reds can at least be plotted on the same graph; Leicester, by contrast, look like 5,000-1 outsiders, which is precisely what they were. Therefore, Liverpool could join Leicester as the only non-Title Zone winners of the Premier League since its inception in 1992.

Now, this means that there have actually been two distinct Title Zones in the Premier League era: 1992-2004, then 2005-2020.

Chelsea raised the bar in 2004/05, and everyone had to follow; Man United quickly changing from a policy of promoting youth whilst making some big signings to almost exclusively buying big. This is when squads got bigger, and there was less time to promote your own academy players if you still wanted to win the title.

Liverpool – without counting any chickens – look like being only the 2nd exception to the Title Zone rule in 28 years. And the good news is that, while the clubs in the Title Zone have shrunk to a third the number from the first part of the Premier League era, the two exceptions look set to occur in the most recent four seasons.

In Leicester’s case it was down to incredible value in the transfer market, whatever their methods of scouting; while Liverpool have allied the power of analytics to the elite man-management and intelligence of Jürgen Klopp, to create a bunch of fucking Mentality Monsters.

(Liverpool’s inclusion is obviously merely theoretical at this point, hence the question mark.)

And, to see the two distinct Title Zones, and just how radically Chelsea changed football, before I move on to more analysis of the current season, see the graph below:

The jump in the Title Zone in 2004/05 highlights how the job Jose Mourinho did – whilst still very impressive – comes with the caveats of what remains unprecedented spending power.

Zonal Spending

And remember, merely entering or remaining in the zone does not make you title contenders: Man United had been in the Title Zone every season of the Premier League’s existence, even when the Title Zone changed*, not least because United began to spend really big on players who cost well over £100m in today’s money, like Rio Ferdinand and Wayne Rooney.

(* That said, you could do a separate Title Zone for 2005-2007, with Chelsea in a league of one, but as you can see from subsequent seasons, it did even itself out again across three clubs pretty quickly.)

However, 2019/20 is the first time United’s £XI has fallen below the 2005-2019 Title Zone cutoff point. With no Paul Pogba, and with Romelu Lukaku sold, they are now “only” a £400m team.

While United remain 2nd in the rankings, above Liverpool and below Man City, the truth is that this season has seen Man City exist in an island all on their own; not least because Chelsea’s £XI has also fallen dramatically, a decline that started with the introduction of FFP in 2010 and their commitment to stick to it.

In 2019 money, Chelsea’s 2005-2007 £XIs remain way ahead as the costliest in the entire 28-year period, and given that the Premier League itself increased spending power from the old football league days, we can comfortably call that the most expensive side of all time. They got in before the financial regulation, spend wildly (which in part led to the financial regulation), won spectacularly, and then set about a period of general decline – interspersed with the occasional big success – that still saw the £XI rank in the Title Zone, at least until this season.

The loss of Eden Hazard – hitherto their most expensive player in 2019 money since the days of Didier Drogba, Andriy Shevchenko and Michael Essien – as well as a transfer ban meant that, like Man United, they are now relying on more inconsistent young players than they’d ideally like, although these could be seasons of pain that lead to greater gain further down the road, if those younger players continue to improve.

Now, all the figures for this season quoted in this piece are for the halfway point of the campaign. Things can still change. The returns from injury of players like Paul Pogba and Aymeric Laporte, if all goes well, will both increase the Manchester clubs’ £XIs.

However, Liverpool’s own £XI should increase slightly as the season unfolds, given that Alisson has only been in just over half the line-ups so far. But even if the Reds fielded their most expensive possible side for the second half of the season, it still wouldn’t reach the Title Zone; and indeed, with Joe Gomez in the defence instead of Dejan Lovren, it’s likely to remain at a similar level.

(Again, the cost of any individual player – Gomez being far cheaper than Lovren – is not representative of their quality now, but a mere proxy of what they were valued at when bought, and then adjusted for inflation. You sometimes get what you pay for, but a lot of the time you get less or more than you paid for, by varying degrees. However, in a squad of 24-30 players, the law of averages usually suggests that you should have a lot of quality if you spend a lot of money; and you certainly have the greater pick of potential signings if you pay the big bucks. As with any model, if you outperform the model you are doing things the right way.)

All this means that for the first time in the entire history of the Premier League, there is just one single club within the established Title Zone: Manchester City. In the late 2000s there were just two teams: Man United and Chelsea. Then, from 2011 onwards there were three teams: Man United, Man City and Chelsea. But now the league is actually more condensed, with just City out on their own. Obviously this just makes Liverpool’s season so far all the more remarkable.

City also have the biggest financial advantage seen in the entire 28-year period covered by the £XI model: the 2nd-ranked team, Man United, cost just 65% of City’s £XI; otherwise you have to go back to the mid-2000s, when United’s £XI was only 70% of Chelsea’s astronomical £748m.

(Note: there has been some deflation in the past year, so the 2019 money figures are not as high as they were in the past when I’ve run such analysis, but obviously any £XI from any given season retains its relationship to other £XIs in that season. All club seasons get applied the same inflation.)

Liverpool’s £XI in 2019/20 puts them almost £100m short of inclusion in the Title Zone, and so, as with Leicester before, it would be a remarkable achievement if Jürgen Klopp’s men hang on – or indeed, further increase their lead – to land a 19th title for the club.

(Edit: that said, Liverpool’s £XI ranks in the top three, so that is another kind of Title Zone: the winners almost always come from teams ranked in the top three, but it’s just that the team in third is not normally this far behind the team that ranks top. Also, Liverpool’s rise from the 5th-ranked £XI when Klopp took over to top three now was achieved in no small part by selling a cheaply-bought player for £142m to spend £141m of it on two players, and through successive trips to the Champions League final, which in turn raised the club’s profile and sponsorship deals. So it was largely self-generated, by success on the field, and only then became self-perpetuating – but had Liverpool sold Coutinho and regressed, there would only be questions about why the Brazilian was sold. Plus, there’s a reasonable chance that Liverpool could still end up ranking 4th this season, with Takumi Minamino a bargain who would only bring the cost down, and with Chelsea – narrowly behind Liverpool in the £XI rankings – apparently due to spend some money in January.)

Perhaps Liverpool are aided by the financial downsizing of Manchester United, as they continue to flounder as a Europa League club, and Chelsea, who had a transfer ban; as well as Arsenal, who haven’t won the title since dropping out of the Title Zone upon the building of the Emirates, and, like United, have become a Europa League club, for the time being. (Liverpool were at that level just three seasons ago.)

But that still wouldn’t explain why Liverpool became the first team to win the European Cup whilst also attaining 97 points in their domestic season; nor how they’ve actually gone from strength to strength in the aftermath.

Liverpool clearly had to rise to the challenge of a new bar set by the impressive Guardiola, but just because you have to rise to a challenge it doesn’t make it any more possible to do so. Often, the gap only increases. And this summer, City spent £60m on a holding midfielder and £60m on yet another full-back (plus repurchasing yet another full-back, to take Guardiola’s total spending on defenders and goalkeepers over the £400m mark before inflation), but went into the season with just one centre-back that the manager seemed to rate.

So City are underperforming this season, as the only club with an established title-winning budget, but I think they deserve to be cut some slack due to the relentless form from 2017-2019, and the fact that the cycle for this team felt like it was nearing the end.

That said, they have also contributed to their own relative demise by not addressing issues in the summer when spending well over £100m; not least because Aymeric Laporte played in all four league defeats last season, but they never lost a single league game – winning virtually every one – once Vincent Kompany was restored to the XI at the halfway stage (although he got very very lucky against Liverpool).

England Is Now Elite

This has also been a season where Leicester were at least challenging for the title when approaching the halfway point with an £XI that ranks 9th, and Sheffield United (the 2nd-cheapest side in the division) and Wolves are having seasons either comparable to, or better than, Man United, Spurs and Arsenal.

Plus, all of the English teams have progressed in both the Champions League and the Europa League, including newcomers Wolves. That’s seven out of seven, on the back of a season when England had all four European finalists.

This suggests that the league itself, despite some flaws, is in exceptionally good health and that – as the ClubELO index shows – Liverpool just happen to be the 4th-best team, statistically speaking, in the history of the game, having usurped the team ranked the 7th-best in the history of football. Liverpool are not making a mockery of a weak league; they are making a mockery of the strongest league in the world. This is one of the reasons why Liverpool rank so highly in the ClubElo rankings: because the league itself is currently at an extremely high level, with even the poorest Premier League clubs richer than some of the continent’s biggest names.

Ergo, rather than this be some kind of problem for the English game, this is actually something to celebrate; Liverpool, with their incredible variety of styles of play (Owen Hargreaves noting recently that they can do virtually everything), and eclectic and cosmopolitan range of key men on and off the pitch – should be nothing less than a national treasure, especially without blanket big-spending and financial doping.

But in these times of opposition, conflict, denial and schadenfreude, giving credit where it’s due is never to be fully expected.