While I try to avoid running into such arguments, I see that some Man United fans began claiming that Jürgen Klopp had spent more than Jose Mourinho, when it looked like Liverpool were going to sign Nabil Fekir, before medical issues scuppered (or postponed) the deal.

Presumably Liverpool will still spend that money, however; whether going back for Fekir or finding an alternative. And Liverpool may also spend a reasonable – or even hefty – amount on a new goalkeeper, plus a winger to understudy or challenge Sadio Mané and Mo Salah.

The problem is, it’s gross spend – the worst argument that can be made about football finances. If you are spending money in part because you’re losing players (which weakens what you have), then that’s utterly different to if you’re not losing players (which doesn’t weaken what you have). Gross spent takes none of that into account.

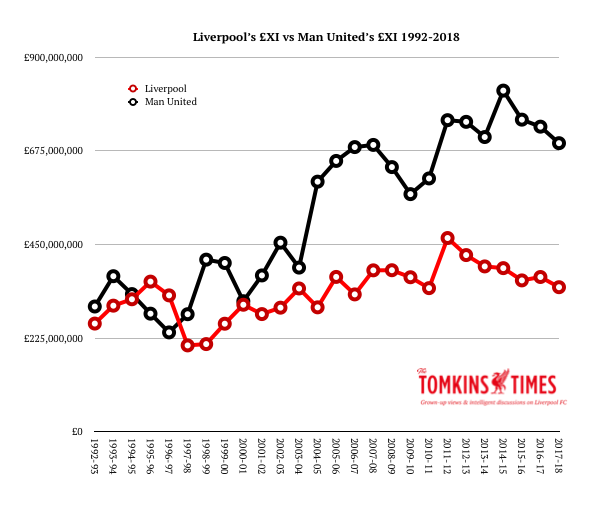

Man United generate their extra money through commercial deals and greater stadium capacity, having pushed well ahead of Liverpool in those terms in the 1990s, in addition to being Champions League regulars until 2014. Liverpool have compensated for a shortfall by selling players.

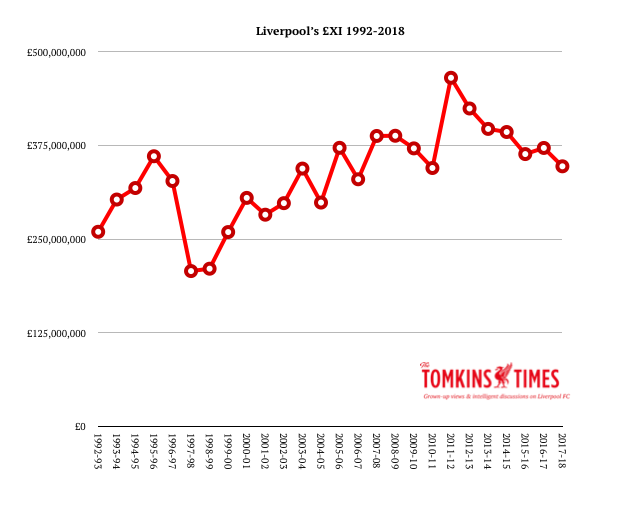

Liverpool actually had a costlier team for a while in the early-to-mid 1990s, as the Reds spent big to try and overhaul United. But since then the gap has mostly grown, and often remained a chasm.

If United sold David de Gea for £150m, then they would be losing a key player, which could pose some risk to future success, even if the funds provide opportunity. However, they are at the top of the European food chain due to their financial might, and so can’t easily be raided (albeit Real Madrid appear to be the only club capable of luring players away, albeit Cristiano Ronaldo’s 2009 fee now equates to over £300m in 2018 football money). To claim to be spending less than Liverpool is wrong in so many ways.

Net spend is a better argument than gross spend, but still flawed; as again, it depends what a manager inherits (can he raise much money from selling, and how many players does he need to buy?), and it can often be used with very arbitrary cut-off points. What about if a club spends hundreds of millions three summers ago, and they still have those players, but you make the cut-off point two summers ago? All that spending doesn’t vanish; the players are still there. You have simply massaged the figures. (Obviously you have to have cut-off points somewhere with spending comparisons, and it may not be intentionally deceptive. But other methods, as I will move onto, don’t rely on cut-off points.)

Man United indeed spent hundreds of millions in 2018 money in the two years prior to the arrival of Mourinho, and while he wouldn’t have wanted maybe half those players in an ideal world, it was still a pretty damn elite – if bloated – squad full of title-winning experience. (This was the same thing Mourinho did at Chelsea: keep half of the preexisting big signings, ditch the other half when spending a fortune; albeit a bigger fortune than he has spent at United, after inflation is taken into account. Chelsea 2004-2007 remain by far the costliest side in the league’s history.)

Compare it to what Klopp inherited – or rather, the perceptions of what Klopp inherited, before he improved several of those players (while being unable to improve others, who just weren’t up to it) – and you’d say Mourinho clearly got the better deal.

Why wouldn’t he, the squad cost virtually twice as much? Plus, the wages are much, much higher, and that gap has only grown with the addition of Alexis Sanchez on insane money. An issue here is that most observers don’t think Mourinho has improved many players, beyond the 25-year-old Jesse Lingard.

When Mourinho pitched up, there was David de Gea, Anthony Martial and the homegrown Marcus Rashford, three top young/ish players, all in great form; but where only de Gea has been trusted since the Portuguese took charge. The two young strikers were very exciting, but Mourinho seems obsessed with experience. Louis van Gaal’s football may have been boring but as he had at Ajax 20 years earlier, he was blooding youngsters – sometimes that’s a short-term pain for a long-term gain. There was also Ander Herrera and Juan Mata, two highly regarded Spanish internationals – and almost certainly more highly regarded by neutrals than any of Liverpool’s midfield (bar Philippe Coutinho) in October 2015 when Klopp arrived. How many clubs have the luxury of someone like Juan Mata as a squad player?

There was also Marouane Fellaini, who cost a lot of money, and while many neutrals (like me) think he’s an elbow-throwing donkey, Mourinho clearly likes to get him in the team whenever possible, often ahead of his own signings, as United launch long balls up to him (which can at times be effective, but is also pretty grim for the cost of their team). Michael Carrick cost a fortune with inflation, and was admittedly mostly melted by 2016, but he was still a quality footballer who played a fair bit in 2016/17. Phil Jones is a bit of a figure of fun, but he cost a ton of money in 2011, and just played almost 2/3rds of United’s league campaign; and started the FA Cup final ahead of Mourinho’s signing, Eric Bailly. Jones is going to the World Cup, so he’s not a walking disaster zone (apart from the odd comical moment here and there).

Chris Smalling, Ashley Young and Antonio Valencia have all been used frequently by Mourinho (while Matteo Darmian has played a few times, too), and it could be argued that Luke Shaw has been mishandled. Very few managers get to inherit perfect squads, but Klopp, and Pep Guardiola at Man City, have been praised by neutrals for improving what they had, in addition to spending. They have each improved several young players and created exciting teams (albeit while Guardiola inherited more, and spent more).

My point is that, two years in, Mourinho was still making use of a lot of expensive/experienced players he inherited – and still relying on de Gea for a lot of points – whereas Klopp has had to sell/loan out players who were patently not good enough (and/or not a good fit, such as Christian Benteke, Martin Skrtel, Lazar Markovic, Mamadou Sakho, Kolo Touré, Jordon Ibe, Joe Allen, Mario Balotelli), or excellent players whose injuries had taken a toll (Daniel Sturridge, Lucas Leiva), and built almost a whole new team since 2016 with what has been recouped. Liverpool were mid-table when Klopp arrived; unable to defend, and unable to score goals when Sturridge was injured.

And any Liverpool splurge this summer will be funded in no small part by losing Philippe Coutinho in January; which, while it can be turned into a positive (buying three £50m players with the money), has clearly involved losing a player who now scores a goal every other game (doing so this past season for Liverpool, and then for Barcelona, and also for Brazil since 2016). Man United haven’t had to sell one of their best players. So that instantly blows the gross spend argument out of the water.

This is why the “£XI” is so important. With Graeme Riley I created the Transfer Price Index in 2010, to track football inflation, and it led to working out how much teams cost over the course of the season: the utilised talent, averaged out over 38 games in the league after applying inflation, and called the £XI.

It’s impossible to find a strong correlation between gross spend and final league position, and again with net spend. It’s too chaotic. But with the £XI you can find a correlation, even if it will never explain everything on its own, due to luck, injuries, form, fixture scheduling, crazy cup runs and just plain randomness.

Gross and net spends often dip and spike violently from season to season, for the very reason that spending requirements change; so the cost of the XI that’s being utilised becomes the key.

Also, in the FFP era, spending has to relate to income (although Man City seem to be finding ways around this). The only way to legitimately earn more money (to then legitimately spend more money) is to increase stadium size (albeit match-day income is a decreasing percentage of the pie), improve commercial revenues, and to exceed expectations on the pitch in order to build a more competitive squad.

Of course, this is harder to do given that richer clubs increase their odds of finishing higher in the league by having already spent more money to start with. (And this applies to poorer clubs than Liverpool who are trying to usurp them.)

It’s a virtuous cycle for the richest clubs, albeit with their own internal divisions (as seen every second year at Chelsea) capable of torpedoing their on-field performance and undermining the “value” of their squad. (And even at Liverpool, this kind of splintered thinking saw Brendan Rodgers fall below par in his final 15 months.)

Even so, an uninspiring and workmanlike Man United team ranked 2nd in £XI finished 2nd in the league, in part due to the enormous squad size and cost. (And with inflation, Man United actually have the costliest squad in England. That said, £XI is a better predictor of league position than overall squad cost, and City’s £XI is the one that ranked top. United had more depth, but City had more quality in the XI, and they were mostly able to avoid injury crises. Had City had an injury crisis – particularly with four or five key expensive signings – then their £XI would have dropped, and United would have increased their chances of catching them, albeit with a plainer style of football.)

This is where Klopp’s Champions League heroics generated revenue that the club could not manage to do under Brendan Rodgers; finishing 2nd in 2014, to potentially start an upward trend, but instead of being able to build on it, there was bad transfer investments driven largely by the manager, and the Champions League campaign was a disaster, with just one win from six games. Liverpool ended up finishing 6th after a dismal end to the campaign, and looked unremarkable in the Europa League in 2015/16, before Klopp transformed the side – without any signings – to reach the final and build some cachet and earn some revenue. If Liverpool can continue to over-perform based on financial might, then it can lead to an increase in financial might, to close the gaps.

In the past 12 months – as yet unrecorded in public financial records – Liverpool’s income has clearly risen (stadium expansion, player sales, Champions League revenue), although the £XI fell slightly in 2017/18, in part because of the delay in signing Virgil van Dijk.

The Reds’ costliest £XI to date was when FSG had that big initial splurge in 2011, funded in part by the sale of Fernando Torres; but it was also the initial investment you see from many new owners, as they try to kickstart a sleeping giant.

(As a note here, some of the £XIs I published last season were in 2017 money; as of this summer we now have 2018 money calculated, which is based on all deals in the 2017/18 season. Average prices are up by 69%, more than I originally estimated.)

But the investment by FSG in players like Andy Carroll, Stewart Downing and (initially) Jordan Henderson was not good value; in sharp contrast to how things are working in recent times under the guidance of Klopp and Michael Edwards. The drop in £XI since 2012 has been in part because 66% of the time there has been no Champions League income to maintain the spending (and one of the two Champions League campaigns was a bust anyway), and in part because Downing and Carroll were sold for big losses, that in some way offset the profit made on Luis Suarez. (And then the Suarez money was erratically reinvested, in terms of talent procured.)

Finally the Reds are established again as a top four side (twice in a row for the first time since the final years of Rafa Benítez), and have done so whilst being a highly competitive European side, too. The trouble here is that six clubs can lay claim to the top four now, so the Reds can’t get too comfortable and assume that the top four is now a given, and make long-term investments – such as huge wage hikes – on that basis. (Which is in part why Leeds United imploded 15 years ago. They budgeted like a top four club, then had to sell what works out at over £200m-worth of players in one season, before being relegated.)

I would expect the Reds’ £XI to rise fairly sharply next season, when the summer spending ends, unless players like Virgil van Dijk are injured and cheaper alternatives like Ragnar Klavan have to play (which will reduce the likelihood of a higher league finish).

Last season van Dijk only played 14 league games, which meant Liverpool had a relatively costly defence (the other three were fairly cheap) only in 37% of matches; lowering the average cost of the side over a full season. Van Dijk playing 38 games would logically increase the chances of a successful league season, as would adding fairly expensive players to the side who are not expensive because of some arbitrary reason (see Carroll, Andy) but because they are hot properties based on talent and output.

(Even then, any price of signing can still fail, but the odds of a successful transfer, aka Tomkins’ Law, average at around 50%, with a 40% success rate on cheaper deals and a rise to only 60% on the more expensive deals. If you have a manager who can buck these trends, as Liverpool appear to have, then you’re onto something.)

Liverpool’s £XI in 2017/18 ranked 5th in the Premier League, at £347m. Basically, half that of the Manchester clubs, but closing the financial gap on Chelsea and Arsenal. Liverpool’s turnover is also ranked 5th.

One thing I noted in our new TTT book Boom! How Jürgen Klopp’s Explosive Liverpool Thrilled Europe was that no other Premier League team has reached the Champions League final with an £XI ranked outside of England’s top four. (I’m also not sure anyone else has sold a key player halfway through the season and still gone on to make the final.) I’ve also noted that extended cup runs, particularly in Europe, can do damage to your league points tally, unless you have an über-squad.

The most recent Deloitte Football Money League can be seen below, and without having compared it to the £XI in advance of sourcing it (other than knowing the order of the English clubs), my theory was that it would have some proportional reflection of the £XI, whereas net or gross spends would not.

2016-17 revenue in £m (v 2015-16 revenue)

1) Manchester United 581.2 (515.3)

2) Real Madrid 579.7 (463.8)

3) Barcelona 557.1 (463.8)

4) Bayern Munich 505.1 (442.7)

5) Manchester City 453.5 (392.6)

6) Arsenal 419 (350.4)

7) PSG 417.8 (389.6)

8) Chelsea 367.8 (334.6)

9) Liverpool 364.5 (302)

So, at that point (the most recently published figures), Liverpool’s turnover was only 62% of Man United’s. Within the ballpark of the £XI, but a bit below it; the Reds’ £XI was 50% of United’s this past season, and 50% the season before, and 48% before that. My guess is that it could be 60% this coming season, although presumably the Reds’ turnover will be more than 62% of United’s, but still probably not over 70%.

It’s also worth noting that the £XIs of the bigger clubs since the millennium have risen dramatically, but it’s all in relation to how they’ve pulled away, financially, from the rest of the league. In the 1990s, everyone was clustered far closer together. So it’s not just that some clubs are richer than others, it’s that it’s now by a much greater degree.

If you looked just at net spends this summer, or gross spends in the past two years, it could be that the spending between two unmatched clubs looks similar. But it’s a nonsense. Unless you terminate the contracts of every player you had two years ago, it’s not a sane way to look at things.

Indeed, if I wanted to skew the facts to make Klopp look like a genius, I could point out that Liverpool ranked 19th in net spend last season, at just c.£6.5m, a fraction more than Spurs, who ranked 20th; two similarly-run clubs who are bucking the financial land-locking.

But a) Liverpool sold Coutinho, and didn’t rush to reinvest the money (keeping their powder dry for this summer), and b) both Liverpool and Spurs still had all their other players. They ranked 5th and 6th on £XI, and finished 3rd and 4th (plus a Champions League final), not 19th and 20th. Clearly net spend was a stupid argument for expected league position.

Net spend did work as an argument for Man City finishing top, but only because they already had 15 great players anyway; most of the key men – Kevin de Bruyne, David Silva, Sergio Aguero, Vincent Kompany, Gabriel Jesus, Fernandinho, Raheem Sterling, Leroy Sané – were already at the club when last season started, so had nothing to do with “net spend” in 2017/18. So overall, net spend is a poor argument, with gross spend an even worse argument.

Inflation

Inflation also plays a huge part in the structuring of teams, because when it’s so rampant, anyone bought two years ago will already seem dirt cheap, just because the landscape has altered so dramatically.

Yes, Virgil van Dijk cost a “world record for a defender”, but players in 2018 cost, on average, twice what they did in 2016; so he’s essentially the same cost as a centre-back signed for £37.5m two years ago.

In relative terms, van Dijk cost less than half of what Rio Ferdinand cost in 2002 (£197m TPI) when breaking the British transfer record (£30m), and incredibly, less than Eliaquim Mangala cost Man City. Now, Ferdinand was an amazing player for United, but £30m for a centre-back still seems a reasonable sum now; to pay that when the average price of a Premier League footballer was nearly seven times lower than it is now is to put it into context.

Indeed, with inflation, van Dijk ranks only 13th in Liverpool’s Premier League spending, just behind Glen Johnson. (One that just jumped out at me is that Fabio Borini works out at £42m. Ouch!)

With the average price of a Premier League footballer more than doubling since 2016, you are going to get record fees in non-inflated terms, just because the market is so raised (just as modern movies will outgross the original Star Wars because it costs more to see a film these days, but that doesn’t mean more people went to see them, or that the new film grossed more if inflation was factored in).

If prices keep rising by the same amount, then if a centre-back costs Man United or Man City £76m in 2020 they will be much cheaper than van Dijk, relatively speaking, on account of the logic of an inflation index. If prices double again, then in 2020 van Dijk will be listed as £150m in 2020 money. If there is zero inflation he’ll still be listed at £75m, albeit Jordan Henderson will still be £67m (based on the inflation up to the point where it freezes).

Indeed, the average price of a Premier League footballer is now 27 times what it was in 1992/93. So around £500,000 was the average price of a player back then, whereas now it’s £13,500,000. So you can’t say Graeme Souness didn’t spend much money on Dean Saunders because £2.9m is now pittance, given that it was a British record in 1991. In current money, Andy Carroll cost £121.8m, which is hardly something I’d say to make Liverpool look smart and clever.

Think of it like this: Liverpool would need to buy a non-world-class striker for £122m to provide the same kind of eye-popping jolt that we got in 2011 when seeing what was paid. And that’s a good image to try and recall when figuring out how TPI works.

This is further proof that Graeme and I didn’t invent all this to make Liverpool look good. Indeed, it was initially devised as a way to compare a current Liverpool manager against their predecessors. There was no bias built in. People just often don’t like the facts that come out of it.

Liverpool Next Season

With the arrival of Naby Keita for a final fee of £52m, in addition to the signing of Fabinho, Liverpool should have a more expensive midfield next season … except that both of those (as would/will Nabil Fekir) work out less money, after inflation, than Henderson or Lallana cost. Where they would be more costly is in replacing the departed Emre Can and the ageing James Milner, and some of Liverpool’s other midfield options.

However, if the Reds spend £60m on a new goalkeeper, then, allied to the presence of VvD for a full season, the £XI could easily top the club high of £465.5m seen in 2011/12.

Liverpool’s £XI last season was £347.4m (in 2018 money), but in 2018 money* the Reds could now feasibly field a +£500m team for the first time in the Premier League era. This would rank them just ahead of Chelsea (£494m), for the first time since 2003, although still be a fair way behind the Manchester clubs, and that’s before they too invest in new players. (*At the end of the season these figures will all convert to 2019 money, but that can only be calculated after the January window closes. Then all previous season’s figures get inflated, too.)

I reckon that a Liverpool XI of Alisson, Alexander-Arnold, van Dijk, Lovren, Robertson, Fabinho, Henderson, Keita, Firmino, Mané and Salah would cost £512m, if (and it’s a big if) Alisson could be procured for £60m.

The issue here is that £512m would not be the average, just arguably the best-possible XI; and the average is what makes the £XI. Chelsea’s average of £494m last season included games without their costliest players. As already noted with Juan Mata, Man United can bring in a really expensive player to cover, just like Chelsea and City can do – to a greater extent than Liverpool can.

But of course, Lallana (£63.4m) and Henderson cost roughly the same, so adding Lallana would keep the £XI high; whereas deploying Gini Wijnaldum (£37.2m) would lower it from the example given.

(As an aside here, you can argue that both Henderson and Lallana are poor value at such big fees, but the reason the £XI works quite well as a tool for analysis is that most teams have players who exceed their transfer fee and those who dip under it. You can beat the system with better scouting and better coaching, but the law of averages tends to apply. You can find Andy Robertsons if you’re smart, but sometimes you need to pay big for a player, like van Dijk. The more money you have, the greater your choice in the market.)

After Lallana, only Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain – whose upcoming season could be wrecked by the injury sustained in the Champions League semi-final – is the only fairly expensive player who could be on the bench if the Reds are at full-strength.

Liverpool currently have almost no big investments on the bench. Bargains like Milner, Joel Matip, Dominic Solanke and Joe Gomez – all better than their transfer fees suggest – are still not (or not yet) exceptional players. But if someone like Henderson was edged down to the bench by the (additional) arrival of someone like Fekir (if perhaps not actually Fekir anymore), then suddenly Liverpool would have a few expensive squad options too. Or if Henderson played and Fekir/Fekir-a-like was on the bench, the same would apply.

Even so, the £XI almost certainly would end up being below the £512m mentioned. For starters, if Liverpool sign a new keeper and he’s out injured (dropping an iron on his foot, for an old-time Liverpool story?), and van Dijk misses a big chunk of the season, then the £XI could dip below £400m, let alone top £500m.

So, to me, that will be the interesting thing to analyse when the summer ends. Whatever the net spend, what could Liverpool’s £XI be next season? (And only in a year’s time can we say what it actually was – and that figure would be subject to next season’s inflation as well.)

As Ever, Some Facts

Man United easily outstrip Liverpool in turnover, £XI and wage bill. That’s a fact. Just as Liverpool easily outstrip Everton on all those same metrics; and one big summer of spending (2017) didn’t change Everton’s fortunes that dramatically. Their £XI last year ranked 7th, and they finished 8th, which was much closer to reality than their net-spend ranking, which was 4th. If net-spend was all that counted, Everton should have finished miles ahead of Liverpool, Spurs and Arsenal.

After Everton, the trio of Brighton, Huddersfield and Watford had the highest net spends, but their league positions were closer to their £XI rank than their net spend rank. Was having a higher net spend than Liverpool, Spurs and Arsenal going to put those four teams above Arsenal? Obviously not.

A high net spend should still logically provide a boost, but it clearly depends on the starting point, and then, how much a team’s best players get to play.

So, I’d recommend sticking to our £XI analysis, or looking at wage-bill data (which can be more accurate in some ways and less accurate in others), rather than fixating on un-inflated, arbitrary net-spend arguments.

Boom! is available in Kindle and paperback format from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com, and in Kindle format from other national Amazon stores.