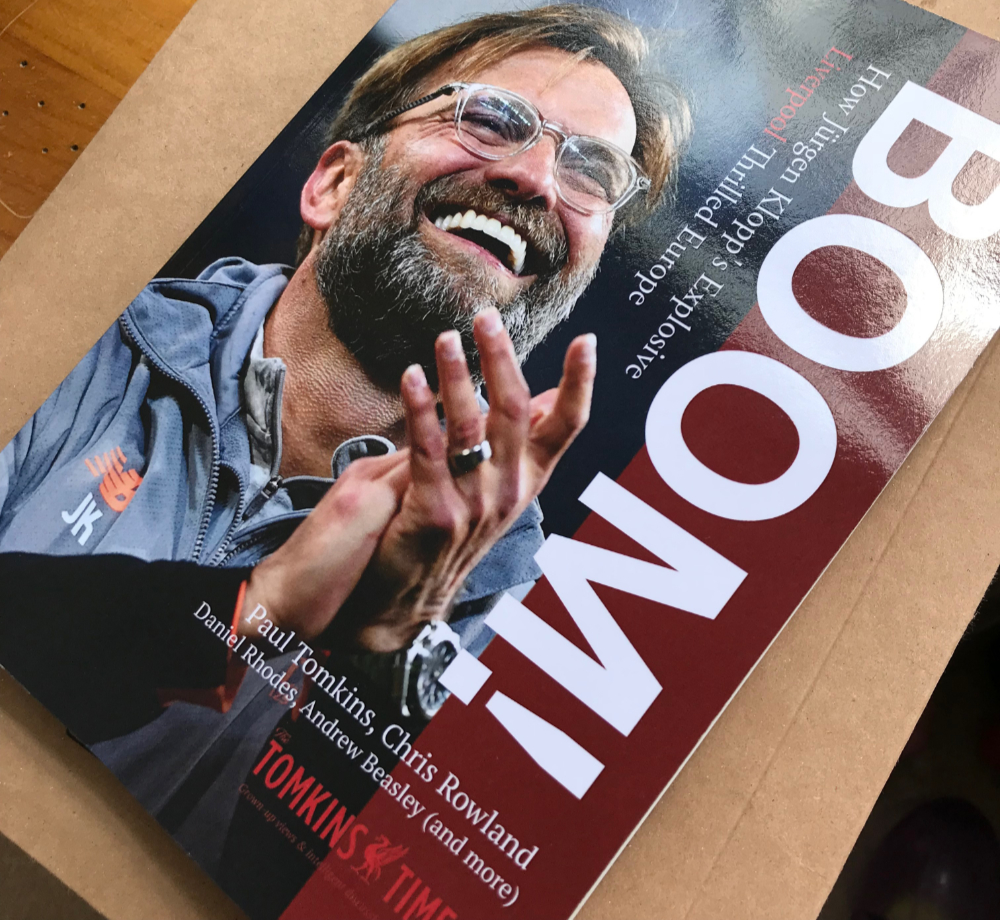

The following is an excerpt from my Introduction to the Tomkins Times’ book “Boom! How Jürgen Klopp’s Explosive Liverpool Thrilled Europe”. Details of how to buy the book follow at the foot of the excerpt.

Step This Way…

A time machine awaits; enter, if you will, and head back to the summer of 2017. Liverpool’s transfer plans are in tatters, up in smoke and wafting signals of concern: Virgil van Dijk, the commanding centre-back the club clearly needs, is being held against his will – or rather, to his contract (those old-fashioned notions) – by Southampton, and the main midfield target, Naby Keita, is equally keen to join the Reds – but his club are hanging onto him too, tooth and nail.

Philippe Coutinho, mirroring those players in the football food chain, hands in a transfer request, and, having apparently gone on strike in August (or at least, had one of those wonderfully timed tactical injuries; the bad back is usually hard to detect on scans) will do so again in the winter, and will be gone in January; no one replacing him when he jets off to Catalonia. So far, all pretty concerning.

Elsewhere, Adam Lallana and Nathaniel Clyne will essentially miss the whole season – although Danny Ings will at least return for a fair chunk of the run-in, after over two years out with back-to-back cruciate ligament injuries. Into the club will come Chelsea and Arsenal rejects, Mo Salah and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain respectively, for fees that some observers find too steep. To many, things are falling apart.

Joining them, a bargain buy from relegated Hull City, who appeases very few of the social media warriors who make so much noise. Daniel Sturridge – virtually the club’s sole source of goals when Klopp took charge in October 2015 – will barely feature, and be loaned to West Bromwich Albion, where he will barely feature. Promising but as-yet-unremarkable striker Divock Origi – one of the few Liverpool players to reach double-figures in goals (twice) in recent seasons – will spend the campaign on loan in Germany, while Emre Can’s season will prematurely end as his contract dissolves to dust. Last season’s club player of the year, and the Reds’ top scorer, Sadio Mané, will be very bright in the first few games, but then get the entire Premier League season’s one and only sending off for a high boot, and after suspension return with his confidence shot to pieces.

Meanwhile, Jürgen Klopp will vacillate between two unpopular goalkeepers – Simon Mignolet’s impressive form at the end of the previous season a distant memory as he loses his confidence, and Loris Karius a fellow lightning rod for criticism.

Stationed in front of Mignolet or Karius will be the much-maligned Dejan Lovren (whom Klopp will stick by, through thick and thin), and, with a severe injury crisis in midfield, the Reds will end the season relying on James Milner and Jordan Henderson in the heart of the team.

The goals will have to come from Roberto Firmino, a centre-forward who is “not a centre-forward”, and who “doesn’t score enough goals”; as well as from Mo Salah, who seems to remain typecast – by some – as the player he was at Chelsea four years earlier, where he scored just twice.

Alberto Moreno – a player who perhaps draws more angst from fans than any other – will start the season by retaining his old left-back slot, while a teenager – along with a player just a few months older – will vie for the role of right-back; as, up front, the young striker, Dominic Solanke, will fail to score a goal in his first 25 appearances for the Reds. To make matters worse, Liverpool face a top-four German side in the Champions League qualifier, as if the start to the season – with four Big Six encounters in the first nine fixtures – couldn’t be more daunting.

Klopp’s men will overcome Hoffenheim – I’ll allow you that much information – but will draw the opening Premier League game away to Watford, and also conjure disappointing stalemates in the first two Champions League games, at home to Sevilla and away at Spartak Moscow, to make qualification from the group look difficult. Early in the league campaign the Reds will lose 5-0 at Man City and 4-1 at Spurs. The last time Liverpool lost by a five-goal margin in the league the manager only lasted eight more games.

With regard to getting decisions from referees, Liverpool will have its worst season in its entire history, eclipsing 1904 for the season when, when balanced out together, the club wins its fewest number of league penalties compared against the number of goals scored, and concedes the most in relation to the number of goals conceded. Liverpool will concede twice as many league penalties as they win, and the only sendings off in games involving them will be theirs.

Spurs will win more league penalties in a ten-minute spell at Anfield than Liverpool manage all season long. And what penalties they do win they will mostly miss. Penalties for clearly accidental handball will become almost obsolete (only six were awarded across all teams in the Premier League all season, which includes deliberate handballs too), yet Liverpool will concede two within a week in Europe. Crystal Palace and Everton will win three times as many penalties as Liverpool in the league.

Liverpool’s excellent league record against the other members of the Big Six (and against Everton) – the foundations of Klopp’s two league seasons to date – will crumble. In the four league games against the two most hated rivals – the blues from Merseyside and the reds from Manchester – Liverpool will end up winless. Late leads against Arsenal, Chelsea, Everton and Spurs will be thrown away. Liverpool will also fail to beat West Brom across three games, even though West Brom are the worst side in the league.

Then, just as the season is approaching its climax, Željko Buvač – the man Klopp calls the best coach in the world, and (very modestly on his own part) the brains behind the operation for their 17 years together – will depart the club under a cloud; cited as personal reasons, with the club claiming that he will return in due course, but talk spreads to a bust-up between the admittedly combustible pair (as has happened in the past, albeit with swift reconciliation). And this comes after the highly-rated Pepijn Lijnders – seen by many as a future star of coaching – leaves to take a managerial job in his native Holland.

With all this admittedly selective information, you’d probably be putting your money on Klopp receiving his P45 and heading back to Germany; or at the very least, you may see a mountain for the (mountainous) man to climb. With all these details then you would not be surprised if it was an utter disaster of a season. It has all the hallmarks: “best” player departing; key transfer targets missed; senior coaching staff departures; and absolutely no favours from referees. Liverpool will concede five goals against Sevilla over two legs, and six against Roma.

Okay, now fast forward to late April, and try to comprehend that Liverpool – unbeaten in the Champions League all season – will be 5-0 up after 63 minutes of the first leg of the semi-final, having just knocked out a rampantly brilliant and incredibly expensive Man City (who are breaking all domestic records) 5-1 on aggregate; won 5-0 in the first-leg of the last 16 at Porto; and put seven with no reply past both Maribor and Spartak Moscow in the group stages.

Liverpool will utterly smash the English record for most goals scored in a Champions League season, and go on to break the entire Champions League record; and it’s front three will edge towards 100 goals between them. With games to spare – and having played ten fewer than in 2001 – the Reds will break their post-millennial record of 127 goals in a season, set when the Reds played all those cup games under Gérard Houllier.

Yeah, I know; it’s a work of fiction. Right?

Bobby Firmino will be a goal away from equalling Michael Owen’s best-ever season, and Mo Salah will be four away from matching Ian Rush’s club record of 47 in a season; both Firmino and Salah scoring just a single penalty each.

Severely lacking match fitness, Virgil van Dijk will belatedly arrive, in January – for a staggering £75m (although this is only roughly half of what Man United paid for Rio Ferdinand in 2002, once football inflation is applied), and the giant Dutchman will certainly make his presence known.

James Milner will be in the team, in part, because of injuries, but then he’ll enjoy a grand renaissance; nothing remotely boring about his season. Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain – in an Arsenal side thumped 4-0 by the Reds in August – will swap allegiances days later and after a tentative start, become a real favourite at Liverpool, until his knee ligaments give out in the Champions League semi-final. Andy Robertson is another who struggles for game-time early on, but then becomes a massive cult hero. Loris Karius has a spell of form so good that the fans’ talk of the necessity to sign a new goalkeeper is put on hold.

Context is everything. Now, as I’ve been noting for over a decade, Liverpool are not part of the elite rich clubs in England; rich in heritage, undoubtedly, but not money, ever since multi-multi-billionaires were allowed to ‘financially dope’ the game. So expectations have to be lower than in the halcyon days – whilst, at the same time, not lowered to the point of accepting genuine mediocrity (Roy Hodgson’s mission statement, if you go back and listen to his pre- and-post-game comments, such as not wanting to get thrashed by Middle-Eastern minnows in preseason and hoping not to lose 6-0 away at Man City, and talking about how formidable bottom-tier Northampton Town would be ahead of losing to bottom-tier Northampton Town).

Despite being the 9th-richest club in the world, the Reds only have the 5th-biggest budget in England. And with Spurs leapfrogging Liverpool in terms of on-pitch performance during the fading days of Brendan Rodgers’ tenure, there are essentially six clubs contesting those crucial top four places each year.

Each season two have to miss out, and this limits the European experience most clubs can rack up; as well as meaning destinations like Real Madrid, Barcelona, PSG and Bayern Munich are more attractive to top players, because as well as the financial might, there’s the virtual guarantee of participation in Europe’s ultimate competition, which could one day morph into a Super League at the rate so many domestic leagues outside of England are being hogged by one team.

The more cash these clubs rake in from Europe, the more they can pay for players, and so a virtuous cycle just gets reinforced by UEFA’s Financial Fair Play rules, albeit the alternative was clubs being bankrolled by billions from oil barons. Liverpool’s place within this hierarchy is slightly unstable, although it somehow manages to punch above its weight in Europe, with five finals in the past 17 seasons; this current season perhaps the biggest surprise since Rafa Benítez took half a team to Istanbul and had to rely on the likes of Djimi Traore, Milan Baros and Djibril Cissé.

Indeed, as I said throughout Benitez’s tenure, in various books and online articles – the aim for Liverpool, in this new financial landscape, has to be to be competitive in May; to have the season not be over when evening games in the spring kick off not with floodlights but with the sun still in the sky; to reach cup finals in Europe, whilst nestled within the top four.

And this last part is no mean feat, either. My research shows that in the Premier League era, cup runs tend to, on average, lower a club’s league position by several points and at least one place; unless the clubs were Manchester United and Chelsea during their periods of peak wealth, 2004-2010.

One of the Rich Three (the two Manchester clubs and Chelsea) having a domestic cup run (which might be just four or five games) doesn’t do much damage, but having two cup runs can; especially if one is in Europe. The smaller the club, the more a cup run can take out of a season, when compared against league performance the year before and the year after, and also when compared against expectations based on their financial ranking. You only have to look at how teams end up resting players for the cups when the season get serious.

Juggling everything – like Manchester United did in 1999, and Liverpool did in 1984 – is just not possible anymore. Chelsea finished 6th when winning the Champions League in 2012, to show that competing on two major fronts is very difficult indeed, at a time when FFP rules started to make the first dents in their spending. And when they won the title in 2017 it was without any European competition whatsoever, just as Leicester had experienced a year earlier (as unexplainable as that success was in almost every other sense).

Liverpool’s only title challenge since 2009 came in 2014, when there was also no European football; indeed, no cup football at all, in reality. All of which puts 2009 into even sharper focus, when the Reds finished 2nd with 86 points, with a small squad compared to the richer clubs, and played both Real Madrid and Chelsea twice in the knockout phases of the Champions League.

What marked out Jürgen Klopp’s success at Dortmund was how he took a team reeling from near-bankruptcy, and brought in cheap, obscure players like Robert Lewandowski, Ilkay Gündogan, Mats Hummels, Neven Subotic, Marco Reus and Shinji Kagawa – as well as homegrown talents including Mario Götze and Nuri Şahin– and elevated them to back-to-back German championships and a Champions League final.

With clever scouting and elite coaching – and a couple of years to configure everything – he was able to smash the living daylights out of Bayern Munich’s financial advantage … until Bayern started simply poaching their best players. No team cycle lasts forever, but Klopp did something truly remarkable in Germany, and in England already averages a cup final per season, along with significant league improvements.

About This Book

This book is a contemporaneous account of the unfolding of the season – of the multifaceted aspects of this thrilling campaign, written in near real-time.

It centres around a series of ‘diaries’ from Liverpool supporters – from those hailing from the city, and from much further afield (around the UK, with others jetting in from Scandinavia, America and Australia) – as they travel to watch the team all over Europe; some seeing their first-ever game, whilst at the other end of the scale, the reflections of two fans who first went to Anfield 57 and 59 years ago respectively.

All this is interspersed with my observations on the football, along with input from The Tomkins Times’ key contributors, as events played out. In addition, we have written some detailed reflections on the season specifically for Boom!, penned as the campaign drew to its dramatic conclusion.

This book also includes some below-the-line comments taken from the site, given that these can often be better than a lot of articles you might read elsewhere. We hope this all adds up to a unique and varied look at Liverpool’s return to the top table of European football, even if it’s impossible to tell the full story of such an eventful 12 months.

As a very brief history to the uninitiated, The Tomkins Times (TTT) evolved from my own personal semi-paywalled blog in 2009 – hence the site’s eponymous title – to a small, niche business that favours quality over quantity. (That said, in-depth reads are quite common, so the word count certainly isn’t tailored to the short attention span. But this book has a lot to cover, and as well as wanting to be as concise as possible, we don’t want too many trees to be hacked down for its printing.)

Although initially my own small site, TTT soon went onto employ writers and editors in the form of Chris Rowland, Daniel Rhodes and Andrew Beasley, plus tactical guru Mihail Vladimirov, until he was poached for a role within professional football (at least three of our writers have gone on to work within the game), as well as technical and support staff.

Aside from the contributions of our paid staff, many match-going subscribers voluntarily shared their experiences at games home and away, all of which was initially taking place before we realised how exciting this season could eventually become; after all, the Reds’ start to the league campaign wasn’t the best – Liverpool were 9th in October – and the first two Champions League games ended in disappointing draws.

However, by the turn of the year it looked as if something exciting might be afoot. So we thought it was worth pulling all these accounts together, along with excerpts from all areas of the site that would make for an interesting, cohesive narrative of a remarkable season as it played out before our eyes. As with my very first book in 2005, the idea – commenced in the winter – was to capture a season, without really believing that a Champions League final was on the horizon.

These submissions have been tidied up a little, with typos and grammatical slips (hopefully) removed. And a few clarifications have been made, in instances where a reference would have been fresh in the readers’ minds at the time but less obvious many months later. However, none of the meanings have been changed, and all conclusions are from the time in question. We think it gives a flavour of what The Tomkins Times is all about, and hopefully captures a very exciting time in the club’s history.

I also think it’s fair to say that we take a holistic approach to football writing; mixing the passion of the game, and what we see with our own eyes – and feel in our hearts, and in the churn of our stomachs – with the kind of insight that only statistics and analytics can provide (in the way that anything counterintuitive is only usually highlighted by data; such as, “The big clubs get all the decisions” – an oft-cited complaint by the followers of smaller clubs – being countered by the fact that Big Six were awarded 50% fewer Premier League penalties this season than the mighty sextet of Crystal Palace, Everton, Brighton, Watford, Leicester and West Ham).

We know that while statistics can be used to mislead, the key is to interpret them properly and honestly. Of course, no statistic can capture the joy of Salah scoring a crucial goal, or Firmino smashing in another no-look finish. Which is why we don’t write dryly about stats, and instead, try to paint the whole picture.

Thank you for joining us on this journey. Buckle up – it’s gonna be a wild one …

For details on how to get your copy of Boom! see here, or use the Amazon link below if in the UK.