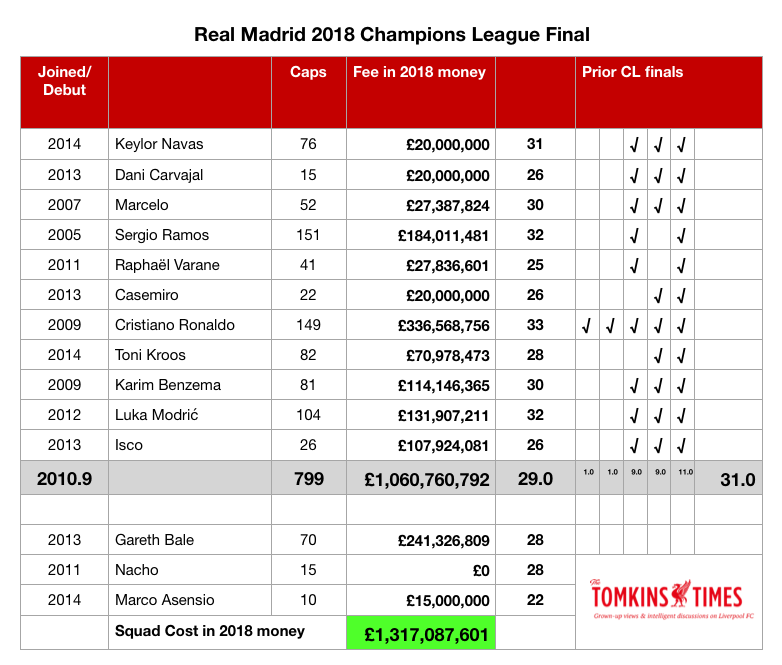

By my quick calculations I believe Real Madrid’s starting XI had no fewer than 31 previous Champions League Final appearances between them; and indeed, it was the exact same XI as last season’s final.

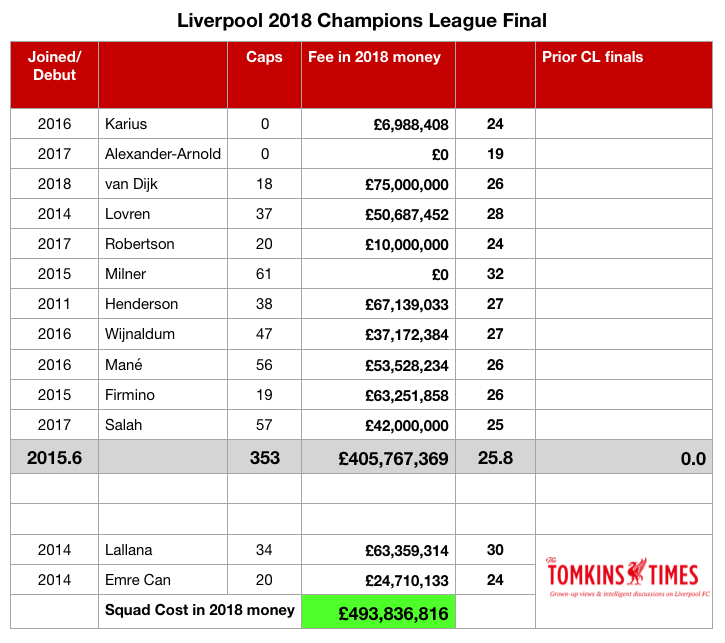

By contrast, Liverpool had … zero.

And while that doesn’t automatically mean a great deal – experience itself comes with no guarantees, if not allied to hunger and an ability to learn from that experience – it does show the difference in top-level nous; in knowing how to deal with situations. (And that’s before getting onto World Cup and European Championship final experience.)

While Madrid’s legs are clearly slowing a little, they were highly unlikely to be overcome by the occasion; and certainly the least likely to make rookie mistakes. If anyone had used up too much nervous energy before the match it was likely to be Liverpool, for whom, without question, this was the biggest game of every player’s life. Nerves are natural, first time around, in anything we do; the same applies to highly paid athletes, who are human, not robots.

The Reds’ most experienced player in international terms was Mo Salah, and he was also the Reds’ top scorer, main threat on the break and an elite creator. It was easy to guess that Sergio Ramos was always going to do his best to put him in hospital; so much so that someone said it to me before the final.

By contrast, Madrid’s players had those 31 finals between them, plus Cristiano “Self Love” Ronaldo has played in a European Championship final, as had Sergio “Pig’s Heart” Ramos, who also has a World Cup winners’ medal, along with Toni Kroos.

Madrid’s average age was bang-on 29, to Liverpool’s 25.8, a gap of over three years. I also saw a stat that Liverpool were the 2nd-youngest ever Champions League finalists, after Klopp’s Dortmund (although I haven’t been able to verify this). What’s true is that Trent Alexander-Arnold was the first teenager to start in defence in a final since 1971.

While Klopp’s first great team wasn’t able to be kept together, its key players went on to win German titles and a World Cup with Germany. They continued to grow as players as a result of that final.

Liverpool right now are, I feel, entering a phase where its elite players can be more easily retained – the sense that Philippe Coutinho will be the last big sale for a long while – but players do get unsettled by rumours, tapping up and big bids (just as the Reds do to clubs like Southampton; it’s the food chain, after all). So nothing can be certain. It’s just that, with qualification for next season’s Champions League secure, and fresh from a run to this year’s final, it’s a little bit easier to convince players to stay; and the boost in money can nail them down to better contracts. It won’t ward off the handful of clubs who can turn players’ heads and offer insane wages to, but Liverpool are at least in a stronger position to deal with it. (Also, there’s no one in the same situation as Philippe Coutinho, who had been targeted by Barcelona for several years.)

In the end, the gulf in experience was just too big. Madrid’s total international caps are more than twice as many as the Reds’, at 799 vs 353, and that’s not including bringing on Gareth Bale (with 70) as a sub.

The unfortunate Loris Karius has yet to play for Germany, and perhaps the occasion got to him. Performing at the highest level is about controlling nerves, and that needs often practice. Alternatively, you can be very young and totally fearless, like Trent Alexander-Arnold (although even he had a spell of two or three games in the early spring where he could do no right, such as at Old Trafford, before turning it around; with a large dose of faith from Jürgen Klopp).

Karius has my full sympathy, and while I think it could scar him for life, the bigger our mistakes, the more powerful they are to learn from. The flip side is that they can end up weighing too heavily; but rather than hate him, I have an extra respect for the way he fronted up to fans for his mistakes. At 24 he’s not a kid, but he’s still a young goalkeeper, with their statistical peak (in terms of their best save percentages based on historical data) between 28 and 30; and in terms of composure, probably later still, before, in their mid-30s, their agility and reaction times dim and they melt away. He’s not a write-off, but you do suspect an upgrade will be sought.

Indeed, this wasn’t even close to the youngest Liverpool XI this season, which has averaged at just 24.2 in the league; with James Milner and/or Gini Wijnaldum replacing either Emre Can or Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain to add greatly to the average for the final stages of the season.

If everyone had been fit, Liverpool’s average age would have been perhaps 24-24.5. And yet, ironically, two of the Reds’ most experienced players were absentees from the XI, and both are below the age of 25.

Both Can and ‘Ox’ are 24, but have over 250 career appearances apiece for big clubs who play in the top European leagues and including caps for their country. Oxlade-Chamberlain had also played almost 40 European games, more than any other Liverpool player bar the 86-game James Milner, the 66-game Salah (who was taken out of the game when Liverpool were on top) and the 47-game Wijnaldum. (Dejan Lovren also has 66 games, but mostly in the Europe League.)

By contrast, Andy Robertson – like Can and Ox, also 24 – has less than 100 games in the top flight and international football combined, and most of those were full Hull.

(Not that it tells with Robertson, but he is in the process of going from an excellent full-back into a world-class one. If he’s this good after so few games, he should logically get better and better; unless he gets injured, which can happen, or he loses hunger, which you can tell is anathema to him. I can picture him aged 77, playing football with kids over the park, and chasing like the Road Runner. Meep meep!)

Otherwise, look through the Liverpool squad and all but a handful of players have played more than 32 or 33 games in Europe, with many having played just 10-20.

For Madrid, their European experience almost exactly matches their international experience – 120 games in Europe for Ramos, 159 for Ronaldo, 100 for Modric, 112 for Benzema, 97 for Kroos, 89 for Marcelo; then 40-80 games apiece for Bale, Isco, Navas, Carvajal and Verane. Their least experienced European player is Casemiro, on 39. If Madrid’s legs didn’t give way, then their experience was absolutely mountainous.

But more than their experience as individual players, Madrid’s experience as a team is incredible; indeed, it’s absolutely phenomenal. The more a team plays together the better it should logically get, in terms of understanding each other’s strengths, weaknesses and wavelengths, until it reaches the tipping point and age and injuries take a toll; the end of the cycle that hits all great teams if there isn’t careful pruning.

I still can’t decide about Zinedine Zidane as a coach as he inherited their entire starting XI – and all three subs! – and while he has to be a very good coach to achieve what he has, it’s not necessarily symbolic of greatness. He took a well-oiled machine and it’s still that exact-same well-oiled machine, only older and wiser. (This is no Bob Paisley building a side by snapping up young lower-league and Scottish unknowns and winning three European Cups.) By contrast, seven of Liverpool’s XI in Kiev arrived (or gained debuts) since Klopp took charge. Liverpool haven’t had the same amount of time to grow as a team.

Madrid are probably right at that tipping point now, about to teeter over into the melt zone – but just about at the pinnacle of the sport. In a year’s time the same players will be an average of 30 years old, and few teams remain elite at such an age; 29 is about the outer limit. There’s almost no way the same XI could play the final for a third year in a row, while the luck (or medical magic) to have the same XI two years in a row is freakish on its own.

For now they can play on autopilot. Their age means that they could not easily handle Mo Salah and Sadio Mané, but once they cheated Salah out of the final it was easier – they only had one dangerous flank to deal with. (And Liverpool could only bring on the mid-paced and not-match-fit Adam Lallana, with Oxlade-Chamberlain crocked.)

A couple of years ago I wrote about how long Liverpool teams had been together, with players at the club for varying periods of time; as a way of pointing out how fresh the “project” was and how strong the cohesive thinking was.

If you look at Liverpool’s best team in the Premier League era – 2008/09 (86 league points and Champions League quarter-finalists) – it was based on a core of long-term players: Jamie Carragher with 12 years in the team, Steven Gerrard with 11, Sami Hyypia with 10, and then Xabi Alonso with five, and Pepe Reina with four. They were all key players that season (Hyypia being phased out, admittedly), and all had time to work together as a unit, for years on end.

Others, like Dirk Kuyt, Fabio Aurelio, Yossi Benayoun and Daniel Agger, were in their third season at the club or in the team – which is longer than six of the Reds’ finalists in Kiev, who ranged from 6-24 months at the club.

And for all Man City’s brilliance this season, it revolved around the long-term core of David Silva, Sergio Agüero and Vincent Kompany; and then Kevin De Bruyne, Nicolás Otamendi and Raheem Sterling, who were in their third seasons at the club. Liverpool’s key-core is far more recently assembled.

In stark contrast to Zinedine Zidane’s side, the majority of this Liverpool team only arrived (or made their debut) at Liverpool in 2016 or later, with two more arriving in 2015. Astonishingly, only Jordan Henderson has done more than four years at the club out of the entire squad. The average time spent at Liverpool for the Reds’ starting XI was just 2.4 years, compared to Real Madrid’s 7.1. These kinds of gulfs are hard to bridge, but again, Liverpool were doing so just fine until their one true superstar was cynically crocked.

And when converted to 2018 money – Graeme Riley has just updated the very latest figures for our Transfer Price Index football inflation project, and inflation this season has been greater than I originally anticipated – and using Premier League inflation as a guide, Madrid’s starting XI cost over £1billion. When adding the total of players introduced from the bench it makes for an eye-watering £1.3billion. Those 14 players include three bought from the Premier League, two of whom were for world record fees.

(As a note here, Spanish inflation may work differently, but it’s only likely to paint Madrid as even bigger spenders, as, relative to the rest of Spain – Barcelona aside – they spent infinitely more than their rivals, not least in the past few years when the duopoly had the biggest possible slices of the TV deal. Their three buys from the Premier League accounts for over half of that £1.3bn in 2018 money, so the comparison is possible.)

To compare, the £XIs in the Premier League this season (the average cost of all 38 XIs adjusted for inflation) are £753.1m for Man City; £693.3m for Man Utd; £494.7m for Chelsea; £366.6m for Arsenal; £347.4m for Liverpool; and £295.4m for Spurs.

For further context, the most expensive Man United £XI on record (from a few seasons ago) tops out at £819.5m, while this season was also the costliest £XI Man City have ever posted (so Pep Guardiola’s undoubted brilliance also required some serious spending). Chelsea under Jose Mourinho remain the costliest side English football has ever seen, with consecutive £XIs of £916.1m and £1.07billion in the mid-’00s, and that gave him a c.£300m advantage over Man United at the time; now at Man United he has a £60m disadvantage to City, although United’s squad is currently the costliest in England (they have more ‘wastage’ than City).

The bulk of the Premier League’s wealth is now spread – albeit not evenly – across six teams, with the Manchester clubs hogging most of the expensive talent, and where Chelsea (who clearly used to hog the most) still a fairly expensive side, ranked #3. Liverpool are overachieving in the league (finishing one place higher than financial rank) and massively overachieving in Europe under Klopp (two cup finals in two seasons).

In Spain, it’s just Real Madrid and Barca who can pay the big fees and wages; and in Germany, Bayern have a monopoly. To me, things are veering towards a European super league, as too many domestic leagues are closed shops. Bayern, Barca and Real Madrid feed off anyone who dares challenge them, and as such, cannot ever realistically finish outside the top four. How long before they field B teams in their domestic leagues and their best teams in some European format?

But most of Madrid’s spending is fairly historical; their biggest buys in the current squad – ranging from £107.9m to £336.6m in 2018 money – are from 2005, 2009 (twice), 2012 and 2013. The notion that they are a club running out of money and borrowing to pay their own wages (as noted by The Telegraph’s Sam Wallace) suddenly makes a bit more sense. Indeed, the big bulk of their spending is wrapped up in six elite players, now aged 26, 28, 30, 32, 32 and 33.

Just compare the differences in age, experience and costs between the two sides:

Note: LFC’s £XI in 2017/18 was lower than the cost of the team in the final. This is mainly because van Dijk played in under half the league games, and so his fee only impacts half the season’s average.

Apex Predator

The time at the club that Real Madrid’s players can boast is incredible, but only because they are the apex predator of European football. No one steals their players. The same applies to Bayern and Barca, although Barca made a mistake in not factoring vast inflation into Neymar’s buyout clause, and were suckered by the dodgy money of PSG; another club buying success on credit. Players tend not to want to leave these three clubs either, as they play the biggest wages and compete annually in the Champions League (selfish entourage-and-party idiots like Neymar aside). In Italy, the talent flows up to Juventus; winning seven titles in a row as their richest club.

Juventus, Madrid and Bayern (and until recently, Barca) are seen as these paragons of “knowing how to win”, as if it’s some great quality to have, but in truth they just hoover up the best players and then remain the only clubs that can afford to pay their wages. It’s no accident. Little changes even when they swap managers. In England, even the top teams can drop out of the top four because there are six contenders. Man United can match the wages of the other über-clubs, but have struggled to nail down a top-four place in recent times.

So it’s not just Madrid’s age but also their time spent together as a team that marks them out as almost unbeatable foes in finals. It’s almost unprecedented.

And even the wage rises they give these players is beyond their means; needing a bank loan to essentially bankroll it. It leaves a bad taste in the mouth, along with the antics of Sergio Ramos, whose foul on Mo Salah was described by experts in Judo and Aikido as illegal within their martial arts, as it’s too dangerous; and Ramos’ elbow into the side of Karius’ head is illegal in just about every sport on Earth, and an ABH charge to most people if it occurs outside a pub on a Friday night. As good as a player he is, that’s not wily knowledge, that’s just being a cunt. He’s part of one of the most experienced and settled back-lines in world football.

Again, by sharp contrast, Liverpool’s back four (and goalkeeper) have only been together for mere months. Of those five players, only Dejan Lovren was a regular in the side before this season, while van Dijk, Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold weren’t even in the team (beyond a game here or there in the case of the latter two) in December 2017. Defences improve with time spent together, as it’s the most choreographed aspect of football; so time will benefit these players, if kept together. Liverpool’s defence is pretty much entirely brand new, and already looks like an improvement. Time should improve it further still.

But for now, in the rest of this article, let me look at how Liverpool can use this difficult experience and build on it. After all, in time I believe Kiev will be seen as a good thing – this kind of high-level, high-pressure practice is priceless, particularly for young players (albeit this applies 50/50 for Karius, who could grow from it, or cave in under its grisly burden).

The rest of this article is for subscribers only. See below for details of how to join our smart and respectful community and read all paywalled articles and comments.

[ttt-subscribe-article]