A recent academic study showed that while there was a brief new-manager bounce in the Premier League, it mostly occurs only with foreign managers. (As quoted in The Times last month.) Which is odd, seeing as many of them are clueless dummies who don’t know the league. The fact that they also win all the trophies is simply an unexplainable oddity. If he was only allowed, then David Unsworth would win all the trophies.

The past month or so has seen the England U17s win the World Cup, just like the England U20 team had in the summer, so, therefore, all is well with English players, and something nefarious must be holding them back (which we’ll get onto, including English coaches outright blaming foreigners, which gives the impression of some British bosses being paid-up UKIPers).

Also in the past month or so, we have seen English managers sacked to be replaced by foreigners (aka Johnny Fs), and foreign managers replaced by English stalwarts, steady hands and all. Roy Hodgson, the 2nd-most boring man in football, has replaced Frank de Boer; David Unsworth is temping since the firing of Ronald Koeman; and Slavan Bilic has been replaced by the outright most boring man in football, David Moyes, after the Scot turned out platinum turds in his previous three jobs. Leicester bucked the trend by going with Claude Puel usurping Craig Shakespeare, who himself replaced the Italian Claudio Ranieri last season. Four sackings already, each time the swing from one extreme to the other.

In my first book in 2005 I noted how Newcastle (who struck me as the best example at the time), when appointing bosses, used to swing from hard man to nice man, old man to young man, and this has become the norm across many clubs. Now, it’s often homegrown to foreign, or vice versa. It may just be coincidental, of course, but it doesn’t say much about the long-term vision at these clubs and what they are actually trying to achieve.

And with all this activity has come the age-old bleating from mediocre Brits about the foreigners taking their jobs, and holding back the best young kids. (Yes, Aidy ‘Fucking’ Boothroyd actually said that.)

As it so happens, at Liverpool, Jürgen Klopp – German, aka foreign – is receptive to English players, young or old. Three English lads who were teenagers (or a couple of months past their teens to finagle the figures) have played for the Reds in the Premier League this season: Joe Gomez, who turned 20 at the end of May; Dominic Solanke, who turned 20 last month; and Trent Alexander-Arnold, who was only 18 when he got his first goal at the start of this season.

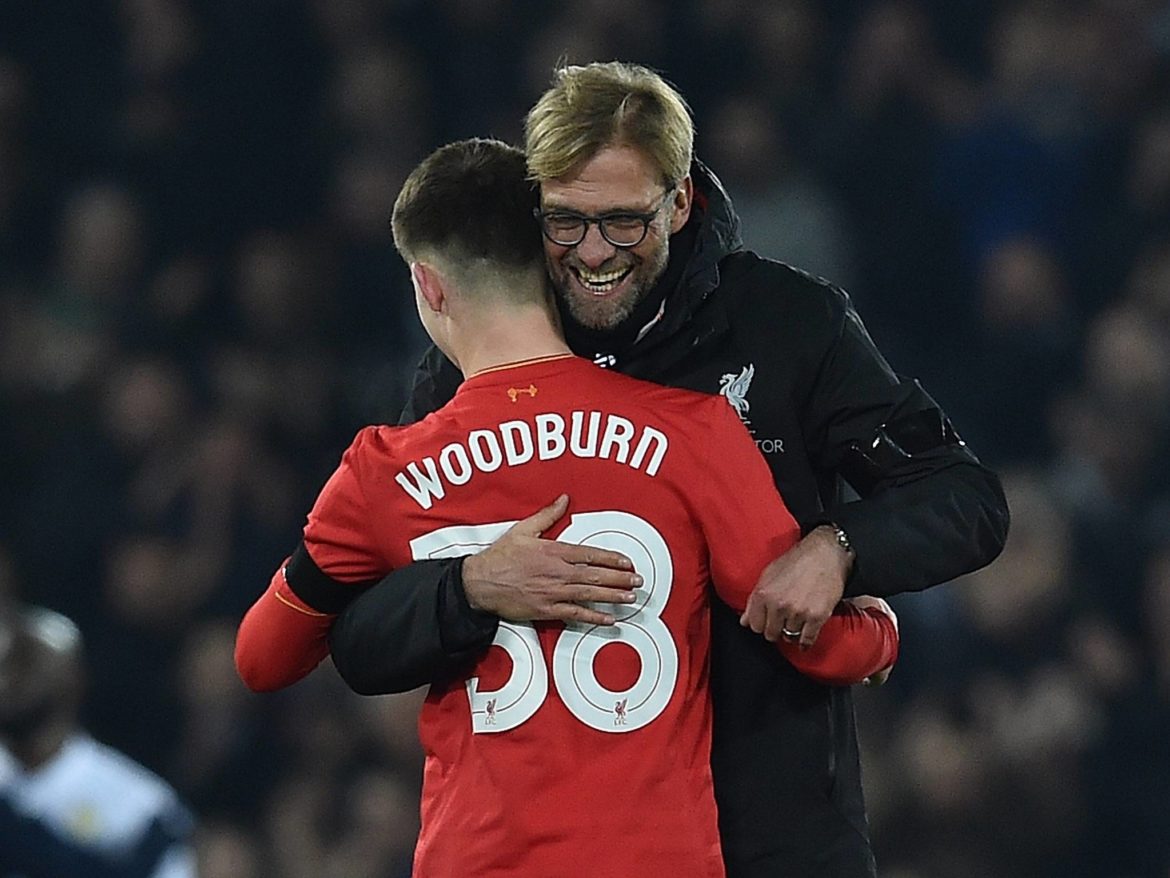

And while he chose to represent Wales and not England (even though he English in birth and parentage), Ben Woodburn scored his first goal last season aged 16, and made his first Premier League start aged 17. He is another young British player Klopp has trusted, but one where patience is also vital.

Meanwhile, Ovie Ejaria, aged just 18 last season, made eight appearances in 2016/17; and while his development has plateaued (as happens), he was shown faith by the manager and is not fully out of his plans. Also last season, Rhian Brewster made the Liverpool bench just days after turning 17.

These are all familiar staging posts for elite talents, with it increasingly rare for kids become full-time starters at big clubs; although exceptions to the rule do pop up. Twenty years ago, an outstanding teen forward may be the third-best striker at a club, because clubs didn’t have four or five full internationals for that position. In 1996/97, when Michael Owen broke through in the last two games, the squad (of the 25 to make appearances) included just Robbie Fowler and Stan Collymore as genuine strikers. Plus one other: Lee Jones, who, aged 24 in 1997, had played just two game for Liverpool in the five years since joining, and who later left to play lower league football.

So with Fowler missing at the end of the season, who was going to play with Collymore? Jones or Owen? Steve McManaman or Patrik Berger could possibly be pushed up front, but that wasn’t their position. Owen was the only logical choice, and it showed that Owen didn’t have to overcome the squad system. He was straight in. And in fairness, he stayed there. But that was 20 years ago, and he was an outlier.

Young players tend to break into the team on a wave of adrenaline and fearlessness, but then they hit a wall – the weight of the experience, physical and mental (and emotional), hits them. It’s much tougher, in all respects, to the football they are used to, so a kind of fatigue will set in; the games are harder, faster, and there are more of them than at youth levels. And, as time passes, the Premier League becomes ever quicker.

Young players tend to dip their toe in the water, then get removed from the vicinity of any water before they’re allowed to go under. While you obviously want a phenomenal break-out star, it’s counterproductive to kill their confidence at the outset. Sink or swim is only good if you don’t care if people drown.

Then they go back to the U23s, playing in largely empty stadia with inferior teammates, and it becomes hard to rev themselves up again. It’s demoralising by its very definition, but equally, they have no right to bypass that process. And struggling in the first team is rarely tolerated, even if people trot out the mantra about “what is there to lose?” (There is always something to lose: the game, the player’s self-belief, the goodwill of the fans, the faith in the manager.)

This quick burst then demotion to the reserves almost always happens, and those who are up to the challenge tend to return to the senior fold within a year or so. Young players tend to remain inconsistent as they haven’t had the experience to play themselves back into form, or to get past the first waves of public criticism. And they’re usually simply not as good as they will be with another few years of natural improvement.

Take a topical example. From Andrea Pirlo’s Wikipedia entry, you can see the familiar pattern. “In 1995, at the age of 16, Pirlo made his Serie A debut for Brescia against Reggiana, on 21 May, becoming Brescia’s youngest player to make an appearance in Serie A. He was promoted by his coach Mircea Lucescu…”, followed by “…The following season, he did not appear with the senior team, although he was able to capture the Torneo di Viareggio with the youth side”.

Then: “Due to his performances with Brescia, Pirlo was spotted by Inter coach Mircea Lucescu*, who signed the playmaker. Pirlo was unable to break into the first squad permanently, however, and Inter finished eighth in the 1998–99 Serie A campaign. Inter loaned Pirlo to Reggina for the 1999–2000 season… After an impressive season, he returned to Inter but was once again unable to break into the first team, making just four league appearances”.

(*My note: of course he fucking spotted him, he was the man who gave him his debut at Brescia!)

So, that’s now six years since his debut, and he played four times for Inter in 2000/01, and was yet again loaned back to Brescia for the second half of that campaign. Inter then sold him to their arch rivals, AC Milan. He was 22, and didn’t do much that first season in red and black. He was still not considered outstanding at senior level, but had a great record with Italy U21s (and before that, U18s, U17s, U16s and U15s). It wasn’t until he was 23 that he gained his first full Italian cap. One of the great players of the past generation, who made his Serie A debut at just 16, and yet his career only got properly going when a year older than Divock Origi currently is.

Of course, Pirlo wasn’t a pace merchant, and to me, those are usually the only ones who seem break through early; or the child-men, built like boxers aged 16.

The second half of this article is for subscribers only

[ttt-subscribe-article]