By Paul Tomkins.

Like an addict trying to kick a shitty habit I greatly reduced my dose of Twitter recently (removing the app from my phone, in an attempt not to be lured back in out of boredom), but continue to be fascinated by the horrors that it can throw up; like car-crash TV, it can be hard to avoid, even if excessive consumption will leave you smearing your own faecal matter on the walls.

So I still occasionally check Twitter, but at arm’s length. It was while checking it during the Augsburg game that I noticed a tweet from the official site congratulating Jordon Ibe on reaching 50 appearances for the Reds. Well done, young man, I thought; concluding that there can’t have been many players to have reached what the official account called a “milestone” at such a young age (20 years and two months). I could think of Robbie Fowler, Raheem Sterling and Michael Owen, whose appearances didn’t even need checking (I’m guessing that all had played between 50 and 100 times by the age of 20-and-two-months). They were all pretty good players, it’s fair to say.

Steve McManaman played his 42nd game for Liverpool on his 20th birthday, and reached the 50 mark at pretty much the same age as Ibe is now. He wasn’t bad, either.

But what about Steven Gerrard? When he turned 20 at the end of May 2000 he’d made 44 appearances for the club – and scored just one goal. (Almost 200 were to follow.) It took him until four months after his 20th birthday to reach the 50-appearance mark. Jamie Carragher had clocked up ‘just’ 26 appearances six months after his 20th birthday, not that anyone was that convinced by him in those raw early days. Ian Callahan broke into the side at 18, but played just nine games in his first two seasons, and then, in the season after turning 20, played 28 games.

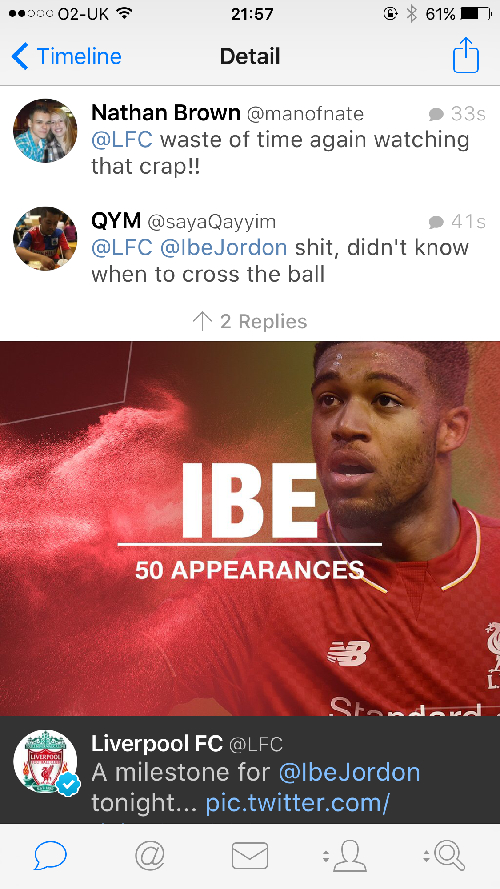

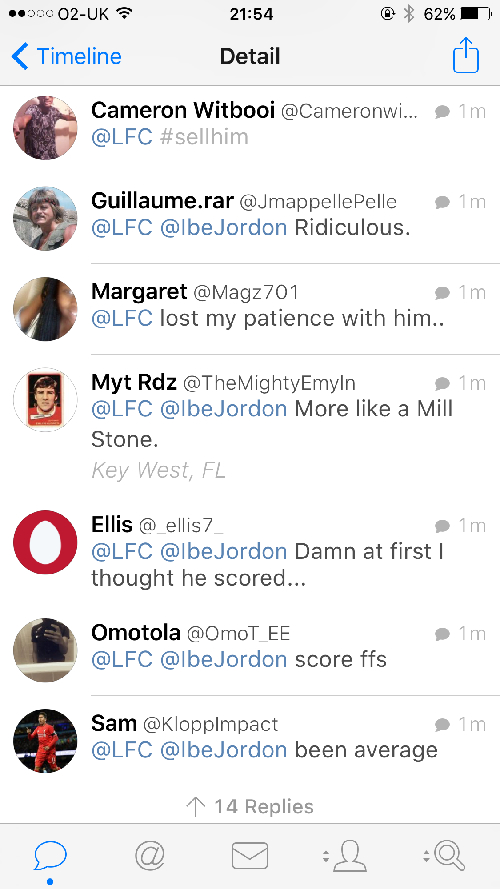

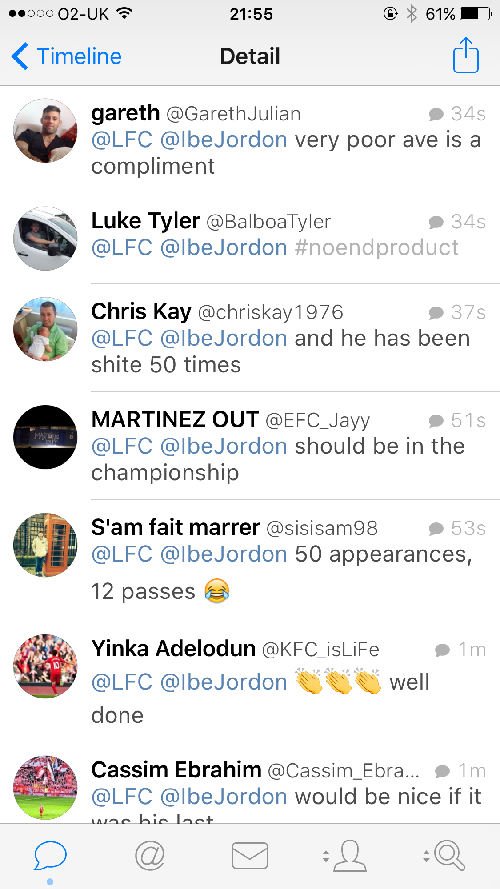

Out of curiosity I clicked on the club’s tweet about Ibe, to see the responses. You can guess what followed.

Every single one, without fail, was criticising or abusing Ibe, with most “copied in” to the player himself, so that he knew full well that people thought he was “shit”, and should be sold. “Zero good games”, someone said. (Actually, there was one single tweet I saw that congratulated him, although by this stage I was starting to wonder if the sender was being sarcastic.)

(Have a look for yourself, before I continue with the article below.)

While Twitter idiocy and abuse isn’t exactly news, what struck me was just how utterly one-sided it was. And just how unhelpful it was, too. If you don’t rate a player, fine; but how does telling him help? It helps you, because you’re pathetic little creatures who need to vent your pathetic little spleens, but how does it enable Liverpool to improve?

Why has destructive criticism become so acceptable? And how can Liverpool thrive as a club, with the need to develop young players to overcome the financial disparity (and with a manager who really does put faith in the kids), when those young players are summarily ‘slaughtered’?

These are the kind of people who tweet the owners to sign Marco Reus, even though, at the age of 20, Reus had just completed a four-goal season in the German second division with Rot Weiss Ahlen, from which point he joined Borussia Mönchengladbach, and only made his Germany debut aged 22. “Sign Lewandowski” they will say, even though, at 22, Lewandowski had only just moved to Germany from the relative obscurity of Polish football, and then, between the ages of 22 and 23, struggled to impress the Dortmund fans, not even breaking into double figures in his first season. Sign “Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang” they will say, even though Aubameyang didn’t hit double figures in a top division until after he’d turned 22.

We don’t want our young players overhyped and idolised, to the point where they lose focus; after all, “Even the tiniest praise weakens you, making you relax” said Javier Mascherano this week (as if parroting his ex-Reds’ boss Rafa Benitez – not someone known to handing out praise). But brutal, stinging criticism, while perhaps providing some motivation to prove people wrong, is also going to damage a player’s confidence, and certainly won’t engender any sense of loyalty to the club. Social media is one of the ways players hear from “fans”, and I doubt it makes them feel wanted, from which point it becomes a more cynical exercise.

Jordon Ibe is 20, barely out of his teens. As is Divock Origi, who got a lot of stick earlier in the season. If either of these was playing regularly in the Reds’ U21 side they’d look head-and-shoulders ahead of everyone else, and fans would be bemoaning that they never get a chance. Because these type of fans are always obsessed with how good youngsters can be, and then instantly turn on them when they’re not as good as Lionel Messi.

There’s no time for them to turn 22 or 23; it has to be now; even though buying new players means a period of adaptation too, and the possible burden of a heavy price tag – and no guarantee of success.

Origi scored 10 goals in 19 games for the Belgium U19 side. Ibe scored four in two England U18 games and four in six U19 games. These are exceptional age-group players. Origi more-or-less bypassed the Belgium U21 side to go to the World Cup with the seniors, while Ibe has just got involved in England’s U21 set-up. And while Ibe isn’t yet prolific for Liverpool, with just two goals to date, it’s worth remembering the earlier point that at the same stage Steven Gerrard had just one.

My general rule of thumb is: cut youngsters slack; cut new signings slack; cut imports a bit more slack; cut even more slack to young imports; and only conclusively judge older signings from the second season onwards (and even then, be prepared to proved wrong; if players change and improve, then the only sensible thing is to acknowledge that, based on the new evidence. Equally, you can’t have limitless patience – and decisions will often have to be made by clubs on players after just one season, if they aren’t settling in, or if there’s a new manager and/or a change of direction).

The 21-23 age point seems crucial. While some players may mature even later than that (particularly defenders), it’s when young players seem to mature. At 21, Alan Shearer couldn’t score goals: despite playing regularly since the age of 17 he’d never scored more than four league goals in a season. At 21, Thierry Henry was a failure at Juventus. At 20, Luis Suarez was doing okay at lowly Groningen. At 22 Sami Hyypia was rejected by Oldham. At the age of 23 Didier Drogba had never played at a level higher than the French second division. At 21, Daniel Sturridge had never scored more than five goals in a season for either Manchester City or Chelsea, despite three seasons where he played more than 20 times for either club.

I’m a big believer in pedigree, and that excellence as a young player is a strong indicator of future success – they’ve put in the hours from a very young age to get ahead of the rest, and if they stay focused they can further improve, to keep ahead of them. But those players have to retain their hunger and their fitness, and avoid serious injury; some will, some won’t. And some players will develop later, as the penny drops and they realise they have to work even harder than everyone else, or because they develop physically (which can go hand-in-hand). Not every kid is built like Wayne Rooney was at 16.

It was recently noted that Kevin Stewart trains harder than anyone in the Liverpool U21 side; and an unremarkable ex-Spurs youth team full-back has developed into a promising holding midfielder on the back of it. If he had merely worked as hard as the rest he may have been lost to the game by now. He’s 22; a relatively late bloomer. He may not be a world-beater, but he shows the kind of improvement that’s possible. He’s worth a place in the first-team squad to help that determination rub off on everyone else.

Barring the absolute world-beating prodigies, for most excellent young players it only really kicks into place at around the age of 21/22 – this is when goalscorers, in particular, hit their stride (but obviously people still focus on the 1990s phenomenon of the teenage goalscoring prodigy and think that anyone who isn’t getting 20 goals a season at the age of 19 is a waste of space). For centre-backs it’s often 25/26 when they find consistency, and cut out the mistakes.

If, like Ibe, you’re playing for Liverpool’s first team at the age of 20, and you played professional football at 15, and have represented England at all junior levels, then you’re probably an exceptional talent for your age group – but you may still be a relatively unremarkable or struggling player in the grown-up world of the Premier League. This is not age-group related – it’s the best of all age groups. So it’s a massive learning curve. Not everyone will make the grade, even if they are talented at a younger age; but not giving them a chance to grow is the biggest mistake. (Which is why I’d have persevered with Lazar Markovic, and I’m eager to see how he does next season under Klopp; he may not adapt and improve, but his ability for his age bodes well.)

Frankly, I am sick to death of fans slagging off young players. Unless those players are out getting pissed (like Jack Grealish at Villa), then lay off them. If they look like they’re not trying then try to take confidence into account, and how that might be affecting them.

One of the tweeters’ avatar is a picture of himself proudly holding his baby. I guess he has never stopped to think what he’d feel if his child were to become an elite sportsperson, and then get tons of abuse at a young age.

Almost any time anyone steps up a level, in any sport, they will experience difficulties. Opponents are generally quicker, stronger, more skilful and, of course, older. All of the older players in the opposition ranks have had years of high-level practice to get better, and stronger, and wiser, and many of them weren’t remarkable aged 19 or 20. They have more experience of elite football, and have adapted.

With Ibe, I feel confident that the main issue now is one of acclimatisation: the sharpening up that comes from repeatedly training and playing against elite players, but which of course takes time. After all, in time, all the elite goalscorers in the world moved from that stage

In Klopp he is working under a manager who is obsessive about hard work, and impeccable standards, and these are the best kinds of managers; they need to know how to encourage, too, but managers who are only touchy-feely don’t tend to hold such high standards. Klopp can do the tactile stuff, but he can also intimidate his players, and, in time, cajole them to new heights.

Fans may feel more disconnected with the players, perhaps due to their salaries, but taking to Twitter to abuse them isn’t going to solve that. It’s going to solve nothing but the selfish needs of the keyboard warriors.

Part Two: Youngsters, and the Difficulty of Scoring Goals

Part Two is for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]