By Mihail Vladimirov.

With Lucas suspended and Coutinho missing through injury, Klopp made only one change to his starting XI from the midweek Europa League clash. Although the manager all but confirmed Allen would be in the starting XI in his pre-game conference, the Welsh player remained on the bench with Lallana replacing Lucas instead. This meant none of Milner, Firmino, Ibe or Benteke was benched.

For Swansea, Monk continued with the same XI that started in their last league game against Bournemouth. The only change was that Sigurdsson was back to replace the suspended Shelvey. The usual starters like Fernandez, Cork, Montero and Gomis all again remained on the bench – perhaps as a way to reward the players who seemingly showed more fighting spirit against the Cherries.

Interestingly, although both teams’ starting XIs seemed nailed on to line-up in a 4-2-3-1 formation, both managers sprang a surprise and decided to go with a 4-1-2-3 shape instead.

Summary

- Both managers sprang a surprise by going for 4-1-2-3 rather than 4-2-3-1

- Liverpool soon achieved full domination

- Two main reasons for Liverpool’s failure to create chances

- The left hand side triangle malfunctioned due to role duplication

- Swansea weathered the early storm and grew into the game, levelling the possession

- The game became flat and uneventful; the teams were defensively resilient but lacked attacking structure and inspiration

- Swansea were unable to fight back once they went behind

- Liverpool retreated deep and defended in a 4-1-4-1 shape

Liverpool’s starting approach

Prior to the game, there were two key questions regarding Klopp’s game plan for this game – how would he approach the game formation and what strategy would he use? As it wasn’t really clear how Swansea would line up, Klopp had to decide whether to gamble and construct a formation (4-2-3-1) that suited his available personnel and disregard the opposition, or whether to go with a formation (4-3-2-1) that should be able to minimise the impact of any surprising tactical decision from Monk. Then, given Liverpool were once again heading into a game with a limited physical resource, the interesting bit was how the German would opt to use it.

Despite his short spell as a Liverpool manager, we’ve already become accustomed to Klopp tailoring his team’s attacking method and overall positional play based on how he and his backroom staff perceive the opposition might struggle to defend as a way to try and exploit their weak areas. So, as much as the actual change was really surprising, the fact there was a change wasn’t really a surprise.

The starting line-up – which also wasn’t surprising at all – that Klopp named here suggested he was continuing with the 4-2-3-1 formation. But following kick-off, the Reds visibly started in a clear 4-1-2-3 shape, the first time that formation has been used under Klopp. This answered the question about the formation.

In terms of approach, the key question was when exactly Liverpool would look to use their limited energy. From the start, trying to blitz their opponent early on, score goals and then sit back to defend what they have; or later on, preferring to first settle into the game and begin with a more patient and methodical style?

In theory it’s always a risk to use all of your limited physical resources early on, as plenty can happen during the game that could conspire to leave you empty-handed. Still, on a purely strategic level it was arguably the right call from Klopp to encourage his side to attack the opposition right from the first whistle. Seemingly, the idea was to see the Reds put themselves in the driving seat for the rest of the game through an early goal or two and the likely reaction of Swansea – given their recent struggles, poor form, shaky morale and fragile confidence – one of despair and heads quickly dropping to prevent them mounting a comeback.

Klopp’s decision to go with a 4-1-2-3 format was supposedly all about enabling his side to exploit Swansea’s usual struggles to defend the inside channels between the lines and being prone to easy wide overloads – the former due to Monk’s insistence on defending in two rigid banks of four without a recognised holding midfielder or natural ball-winner, and the latter due to Ayew and Montero often not tracking back quickly enough to support their full-backs.

The plan presumably was to use the 4-1-2-3’s inherent capacity to construct wide triangles on either side and use them to direct the play right into Swansea’s supposed weak zones.

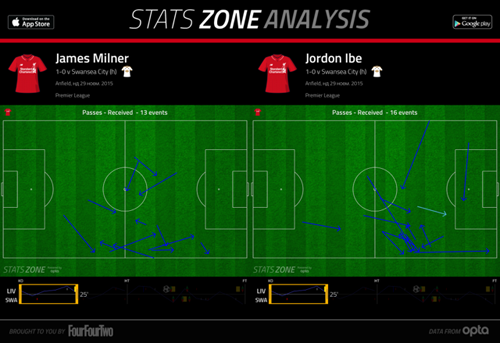

On the left-hand side, Lallana – playing as the left-sided central midfielder – was expected to combine with Moreno and Firmino to create a highly versatile and interchangeable triangle due to the diverse roles expected of each of those players. Typically Moreno would be the sole wide outlet, with the two roamers Lallana and Firmino given greater positional freedom to influence the play from between the lines before heading in and around the penalty box to provide the required extra attacking bodies.

On the opposite side, as is often the case when Ibe plays, the team would provide that extra attacking width with him and Clyne, always keen to overlapping from deep, teaming up down the flank. Here, the presence of Milner and his natural inclination to drift wider meant the team was even more wing-oriented and set up to create wide overloads. The difference of how both wide triangles would behave secured that nice spread-out going forward and the required extra attacking fluidity.

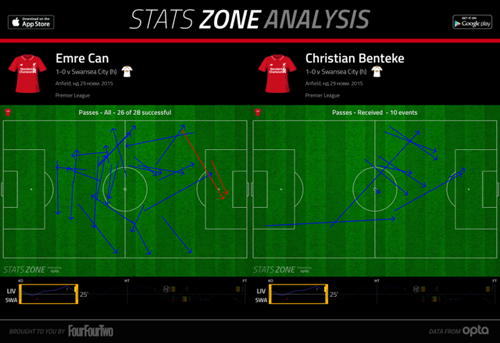

Such emphasis on wide spread-out and creating triangles down the channels meant the players remaining central also assumed very important roles. Can would have needed to remain deep and essentially glue the two triangles together, while still staying in position ahead of the centre-backs to hold the fort and prevent the opposition easily cutting through on the break. Meanwhile, Benteke needed to provide the static focal point occupying the centre-backs and around whom the roaming players down the channels could interplay freely.

The other main benefit of switching to the 4-1-2-3 formation was – especially with such emphasis on creating wide triangles – its inherent capacity to use the shape to press efficiently inside the final third and down the channels. As such the Reds used the structure naturally enabled by this formation to find joy in terms of possession and territory, but also to ensure their supremacy extended to when they were out of possession too. Due to Liverpool’s pressing intensity, Swansea found it very hard to use the ball as a way to get out of their half. The sudden swarming press in packs applied by Klopp’s side often pushed them backwards and forced them into poor passes that eventually squandered possession. All this ultimately served pinned Swansea back and achieved full-blown domination (in and out of possession) for Liverpool.

Liverpool’s attacking struggles

However, for all their success in terms of possession, territory and pressing, Liverpool hardly managed to convert the solid platform they secured into opening up the opposition. There were two main reasons: firstly, it became clear Swansea, like Liverpool, had deviated from their usual formation and lined up in a 4-1-2-3 formation when the starting XI hinted at a 4-2-3-1 one. This made Liverpool’s surprising tweaks and supposed game plan largely redundant, or at least not as suitable as it seemed otherwise. More on Swansea’s approach below.

The other reason was all of Liverpool’s own making. The home struggles to make the new format function properly didn’t help and was arguably the key factor. As a whole the team was obviously not at their best, with mounting fatigue and limited scope for rotation legitimate explanation for the poor touches and the lack of high level movement fluidity and devastating passing fluency seen against Man City. However, there were also certain tactical issues which had at the very least the same negative effect as the fact the players’ lack of full fitness and freshness.

The right-hand side unit did what was expected from them. The trio continually overloaded that side of the pitch, often forcing more Swansea players to shift across to provide cover, which left gaps between the lines and over the opposite channel. But the left-sided trio’s malfunctions, which carried shades of one of the many tactical issues seen under the previous manager, prevented Liverpool’s overall system functioning properly going forward.

There were games under Rodgers when Liverpool couldn’t really spread out in attack in a way that naturally provides the intended balance and complementary distribution of players’ positions and roles down the pitch. Instead, certain players looked inhibited and stifled due to duplication with other players’ efforts, which ultimately left the team lacking in attacking diversity. Often, the previous manager’s inappropriate usage of Lallana and Coutinho in either 4-1-2-3 or 4-2-3-1 was the trigger for such tactical problems.

Exactly the same thing happened in this game too – the only difference being that it wasn’t Coutinho taking part but his fellow Brazilian Firmino, and Lallana. Both of them also largely overlapped and ended up duplicating their roles in roughly the same part of the pitch – that inside-left channel between the lines. As a result, both players’ influence was greatly reduced to the point of almost non-existence.

This analysis is for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]