By Paul Tomkins.

Part One

Can Liverpool Win the League?

Nearing the halfway mark of the season, rumblings about Liverpool winning the title have begun – this despite a fairly poor start to the campaign. The fact remains that Liverpool are just six points off the top, having already played their seven most testing away games. That’s quite startling. As Neil Atkinson said on the Anfield Wrap website, “There’s a league title going here”.

However, talk of titles is a bit more complicated, as I will move onto. (A quick bit of advice: get yourself a coffee.)

I thought I’d try and make sense of the scattered order of the league, even if, after Liverpool’s victory over Swansea, five of the top six are teams who regularly finish in the top six. The Rich Three, plus Arsenal, aren’t exactly firing on all cylinders; with Chelsea, this year’s odd one out (there’s often one), down in 14th. Still, three of the top four are the usual suspects, with Spurs in 5th and Liverpool now up to 6th.

It’s interesting that Spurs and Liverpool, the two clubs accused of wasting the money they received from the sales of Bale and Suarez – their respective world-class talents – (as well as being criticised for not hanging onto them in the first place) are two clubs who are emerging as strong top four contenders and outsiders for the title, whilst also enjoying some fine cup form. The clubs are linked by their hard-running and fast-pressing styles, as well as being the two youngest sides in the division. (Spurs’ average age is just under 25, Liverpool’s is 25.6, with Newcastle the only other sub-26 team.)

The problem with buying six, seven or eight players in a summer is always that some won’t settle, and some just won’t prove good enough (either because they simply weren’t good enough, or various other reasons – injuries, failure to settle in England, unsuitability to the league or the team, or a better player emerging in their position.) But what we’re seeing is that the younger buys by both clubs are improving, whilst one or two others are coming through the ranks. It just hasn’t been an overnight process.

Spurs’ relative success is in part down to players bought for reasonably big fees after Bale’s departure: Christian Eriksen, Toby Alderweireld and Dele Alli (while Mousa Dembele joined in Bale’s final season). And at times Nacer Chadli and Erik Lamela show that the initial reinvestment of the Bale money wasn’t as bad as previously thought, given that some of the players simply needed time to settle and gel. (Occasionally players seem to be on the same wavelength from the start, but this is rare.) It also needs the right manager to get the best out of them. Crucially, if you buy young players you need to give them time; just like Bale himself needed about three years to look better than awful, having been a bargain teenager.

But any time you sign seven or eight players, whatever their ages, you’ll do well to get four of them as clear successes, and perhaps only one will become a real star. (Aka ‘Tomkins Law’.)

Similarly, Liverpool’s reinvestment of the Luis Suarez money doesn’t look quite as bad, 18 months on, as it did towards the end of last season. If the Reds are to finish in the top four, or indeed mount a title challenge, it will be partly down to this spending.

Obviously, with hindsight (and some foresight), the £16m spent on Mario Balotelli would have been better invested in a new block of toilets in the Main Stand redevelopment, and the £4m shelled out on Rickie Lambert could have covered the stadium expansion’s concrete bill (which would have moved faster). With Lambert sold for £3m, if Liverpool get back half of that £20m combined (i.e. £7m for Balotelli) it’ll be a decent rescue.

The £20m spent on Lazar Markovic could yet prove inspired, given that he’s still only 21, and that Jürgen Klopp may like his pace and skill – although the Serb’s lack of aggression may work against him (he just seems too laid back). Still, you’d think that he would be an interesting option for next season – even if he can’t affect this one. (Meanwhile, Javier Manquillo’s loan was cut short – another player Klopp may have liked, even if he wouldn’t have been first choice.)

But Liverpool’s revival under Klopp is down to some of the supposed duds of Rodgers’ final full campaign. Alberto Moreno (23) may never be the perfect defender, but he is now looking like an international-class overlapping full-back, with searing pace and, strapped into the body of a midget, the lungs of a giant. And Emre Can (21), whilst not quite as comfortable in the holding midfield role (although Ruud Gullit only focused on the negatives on MOTD2), has been a more-or-less ever-present fixture in midfield for Klopp, and is maturing as a player all the time. His quality is easy to see; his positioning play will improve with time and experience.

In the last few games, Dejan Lovren has shown that he can be a solid stopper when playing in a balanced system – like the one Southampton used. A constant criticism I had of Brendan Rodgers over the years was that none of the centre-backs ever looked good, because there wasn’t sufficient protection. Rodgers’ teams could look good in other ways; just never at the heart of the defence.

And even Adam Lallana has played an important role in the hard-pressing Klopp has deployed, even if he has yet to score a league goal this season, and in truth, has rarely looked like doing so. Divock Origi (20), signed 18 months ago, only arrived in the summer, and is currently going through the adaptation process, which could still go either way – he’s struggled thus far, but we need to be patient. (His chances will be further limited by Klopp’s single-striker system, but never write off a 20-year-old striker. Harry Kane wasn’t in Spurs’ side at that age. Jamie Vardy wasn’t even in the football league.)

So while it still doesn’t make for a great summer’s work, some good has come of it, with further improvements possible from the younger players. It’s also worth noting that one of the stars of this campaign, since the change of manager, was another once-maligned U-23 signing, Mamadou Sakho. (While a key absentee has been another, Jordan Henderson – whose first season, aged 20/21, was fairly difficult.)

Indeed, you can go so far as to include Lucas Leiva – always a pivotal player in the correct system – in that list. That would mean that Lucas, Can (barely used initially), Moreno, Sakho and Henderson – all aged 20-23 when signed – have gone from being written off to key players within a couple of years of arriving. (While Daniel Sturridge was written off elsewhere.) It takes time, and the right environment, to give these players the best chance of succeeding. Meanwhile, Philippe Coutinho, just 20 when signed, gradually went from a promising ‘luxury’ player to something approaching a talismanic figure.

Another key player in any bid for the top four is Roberto Firmino, who was ludicrously written off earlier in the season, after a summer spent playing for Brazil interfered with his pre-season, and when Liverpool’s manager at the time didn’t seem to know what to with him (before a back injury forced the player out for a month). Firmino was average (perhaps leggy) against Bordeaux and Swansea, but sensational at City – although the key differences were that he played further forward, it was an away game, and that Coutinho was alongside him. (Also, like a lot of Liverpool’s players, he may not have done the kind of fitness work in preseason that Klopp would find ideal for his methods – which is not to say that Rodgers trained them incorrectly, just that it may not be what Klopp required.)

You sense that any success Liverpool have this season will be aided by the understanding the two attacking Brazilians have: an instance where two excellent players exceed the sum of their parts. But if Klopp doesn’t have the perfect squad, he has these two, plus two top Premier League strikers in Benteke and Sturridge – if the latter can stay fit.

The impressive run the Reds are on has been achieved without Sturridge (bar 15 minutes), Henderson (bar 20 minutes), and with the instant hits Danny Ings and Joe Gomez out for the campaign. It has been achieved with various other absentees, too.

Jordan Ibe’s resurgence after losing his way (as youngsters do) is another big bonus, even if his final ball remains inconsistent. You can see how Klopp has worked with him on his game (particularly his turns), and he remains a great 19-year-old, with the potential to become a great player, full stop.

James Milner has been steady at best since joining the Reds, but appears to be a good calming influence, and can take a mean penalty – something the Reds needed, with the departures of Gerrard, Balotelli and Lambert. He has title-winning experience, and while that may not count for a lot, it can be reassuring (as long as it’s not replaced by a lack of hunger, and that can’t be said of the former City player).

Another impressive addition has been Nathaniel Clyne, whose defending is superb, and whose overlapping runs are like the metaphorical express train. His quality on the ball isn’t anything special (if it was he would be a £30m full-back), but he provides a nice counter-balance to Moreno; and even if his touch is mediocre when he gets into the final third, it’d be brave opposition that ignores those eye-popping runs.

So the basic components are there for a strong season – not least the inspirational manager, and his knowledge of what it takes. But it’s still hard to see Liverpool winning the league, from the position Klopp inherited, and with the weaknesses in the squad.

Part Two

The rest of the League

While I think that Liverpool’s chances of the title remain very slim, the odds on finishing in the top four are starting to look pretty reasonable. I’m certain that Leicester won’t finish in the top four, and fairly sure that Chelsea won’t be able to claw their way back above the current top six, unless any of those clubs have a meltdown.

Indeed, Leicester will do well to finish 7th; any higher seems incredibly unlikely. Finishing 7th would be a big achievement in my eyes, whilst finishing 5th or 6th would be almost unprecedented in the modern game. Obviously Everton, Blackburn, Aston Villa and Newcastle, while not the forces they were, were still fairly big clubs, with reasonable budgets, when they managed top six placing over the past decade, and you have to go back to 2004/05, and Bolton, for the last ‘unfashionable’/(fairly-)recently-promoted side to finish in the top six, and before that, Ipswich in 2001.

Aston Villa had the 6th-costliest £XI when they finished 6th under Martin O’Neill. Newcastle ranked 9th in the £XI table in 2011/12 under Alan Pardew, so they ‘only’ overachieved by four places, whereas Leicester currently rank 18th. To finish 8th when ranking 18th would be incredible. To finish 1st would probably be the greatest achievement in the history of English football.

I argued last season that Southampton would drop away, and they did. On this date last season, after 12 games, they sat 2nd, two points ahead of Man City and four ahead of Man United. They did incredibly well to integrate so many new singings, but their £XI-rank for the season was 9th, so they ‘only’ overachieved by two places. Twelve months ago Arsenal were 6th with 20 points, and Swansea were 7th. Spurs were 10th. And after nine games, West Ham were in the top four, and still as high as 5th after 13 games.

By the time of the final table, the six richest clubs occupied the top six places. Maybe one day a genuine early-season surprise will hold out until the 38th game has been played. But I find it hard to see Leicester doing so (even if I’ve lived in the city since 1999, and should perhaps be kinder to them to guarantee my personal safety).

It’s now highly rare for a smaller club to finish in the top six. People say “Why can’t they stay there?” and the answers are: because a league isn’t even close to being representative until every team has played each other, home and away; that the bigger squads come to the fore in the second half of the season as tiredness and injuries take their toll; that the better players in these teams will start getting linked with moves in the January window and possibly lose focus (some may even be lured away mid-season); and that the initial fun of being there, which is like a dream, turns into pressure as soon as it feels like it’s suddenly theirs to lose.

I see this all the time in individual matches, and I always think of the 2006 FA Cup Final. The team that is not expected to do well (West Ham) plays with freedom until they go two goals up. Then thoughts either turn to “we’ve done this!”, which leads to a drop off in intensity (the job is done), or the fear of losing what they never thought they’d have. The favourites (Liverpool), who were nervous under the weight of expectations, were freed up by going 2-0 down, and only got nervy again once it got back to 2-2. West Ham, once they’d thrown away the lead, were then free to play as underdogs again.

If you do the lottery, and don’t check your numbers until a day later, and you see that you had five of the six needed, you’d be bitterly disappointed – but no mental pressure will be experienced. However, if you watched it live, and the first five balls came out in the right order for you, then that sixth letting you down will severely mess with your mind; close enough to taste, but no cigar.

Or to use another lottery analogy, if you didn’t put your numbers in one week, and you discover that you would have won £10m, then you’d have exactly the same finances as before, but now you’d feel £10m worse off – even though you technically never had the money to lose. It’s the knowing that does the damage; if you failed to put your numbers in, and they came up but you weren’t aware of that fact, your life would be totally unaffected. At some point, teams unexpectedly leading the league have to face that reality, and shit gets real.

For me, even after such an amazing start, Leicester should still see finishing mid-table as a successful season. (As with all clubs, I don’t watch them as much as I watch Liverpool, so I may be missing something.)

Whilst on the subject of mid-table, a brief aside about Gary Monk, given that his job is under scrutiny, and that he was the opposing manager yesterday. To my mind, Monk hasn’t done enough to suggest he definitely has what it takes – the hype was gloriously premature – and nor has he been bad enough to warrant the sack. I find him almost impossible to assess, even if he has some neat ideas according to those who have spoken to him.

He was an insider at a club that is famously well run, and so he didn’t need to change much: he already knew what worked and what didn’t. The players seemed to like and respect him, but they already knew him anyway, and so things continued much as you’d expect. Equally, you’d also expect a dip at some point – which is happening now. None of this tells us anything about Gary Monk as a manager, other than he’s not totally hopeless.

(The other thing that sees managers fail is simply being the wrong fit – not understanding the club, or what supporters expect, or fitting in with the style of play the personnel are used to. Monk was never going to have that problem, as he played almost 300 games for the Swans, across all four professional divisions. Quite how he’d fare walking into a club where the fans don’t care about that, and where the players wouldn’t necessarily respect keeping a mid-level Premier League club on an even keel, is another matter.)

Anyway, getting back to the league table – how can it tell the truth when Liverpool, for example, have played away at Arsenal, Man United, Everton, Spurs, Chelsea and Manchester City? That could not be less conducive to being fair and balanced; the balance comes when the return fixtures have been played. Even then, it can perhaps be hard to make up ground that can be lost with a ridiculously tough start; by the time the home games come around the pressure of a struggling campaign might be telling. (A league is also not totally fair if cup games are scheduled to make life harder.)

As for Chelsea, my guess is that they will work their way up the table, but at best I can see a finish of 5th or 6th, because making up such a huge deficit leaves little leeway; it’s one thing to go on long unbeaten runs when you’re riding high in the league and full of confidence, knowing that you can lose a couple and still be on top; but when starting from a lower point it tends to fall apart once a decent unbeaten, or winning run, comes to an end. (Drawing at Spurs is a pretty good result, but it doesn’t help make up for the points unexpectedly lost.)

It happened to Liverpool last season – an excellent mid-season run after a poor start looked like the Reds were back on track; but once they lost to Man United it effectively killed any hopes of a top-four finish, with five points and +13GD the difference to United in 4th after that infamously dire day, even though it left eight games still to play. Liverpool not only lost the game, and their belief, but went into an absolutely dismal spiral. Manchester United under David Moyes and Liverpool under Roy Hodgson had periods of resurgence, but after poor starts the overall picture was poor. (The same happened in Rafa Benítez’s final season at Liverpool, where the revival proved to be too little, too late.)

Also, my sense is that, like Liverpool in 2004/05 and indeed Chelsea themselves in 2011/12, Chelsea will start to focus on the Champions League at the expense (intentional or otherwise) of league fixtures. If Mourinho’s men start winning league games a bit more frequently over the winter, as you’d expect, and they get up to 7th or 8th (to get any higher before spring they’d need others to really slip up), it may coincide with the knockout phases of the Champions League, and it will make sense to go all out for that. The top four is important, but it’s hard to chase it in the way that you would Europe’s elite trophy.

A league defeat or two would suddenly make the top four look fairly distant, and it’s hard to imagine a team that has lost seven of it’s first 14 league fixtures going unbeaten for the remainder of the season; the underlying confidence is too brittle, and easily shattered when seriously tested. Weirdly, earlier in the season I fancied Chelsea to win the Champions League, after making such a poor start – the focus could switch. For five years in a row under Rafa Benítez Liverpool seemed to reach a point where, even if it was only for a few games here and there, it was a question of the cups or the league. Only the über-clubs seem to win the Champions League whilst excelling in their domestic league.

It’s incredibly tough, particularly in the Premier League, to go for the title and the Champions League at the same time. It’s debatable if our league is the best for quality (I don’t think it is), but it’s certainly the most demanding, with more league games than in many other countries, and an additional cup competition, allied to no winter break. In addition to that, referees keep the games flowing, which makes games faster and more dangerous.

And as I’ve been noting for years, our country has three elite rich clubs (Spain has two, Germany one), plus it has two distinct ‘heritage’ clubs in Arsenal and Liverpool who, unusually, are not part of that current wealthy elite (whereas in Spain and Germany, the traditionally glamorous clubs are naturally the rich ones; in England, Chelsea and Manchester City, although not lacking league titles in their distant history, ‘bought’ their way in, with only Manchester United fitting the Barcelona/Real Madrid/Bayern Munich model). That said, Arsenal are edging towards the Rich Three, and what I call the Title Zone.

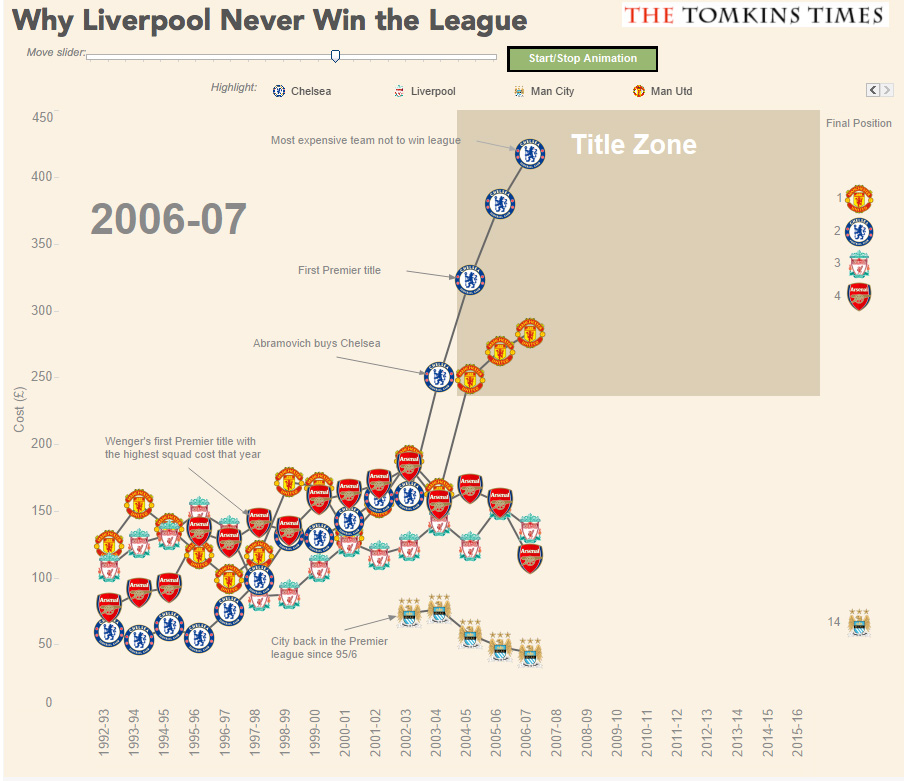

Part Three: The Title Zone

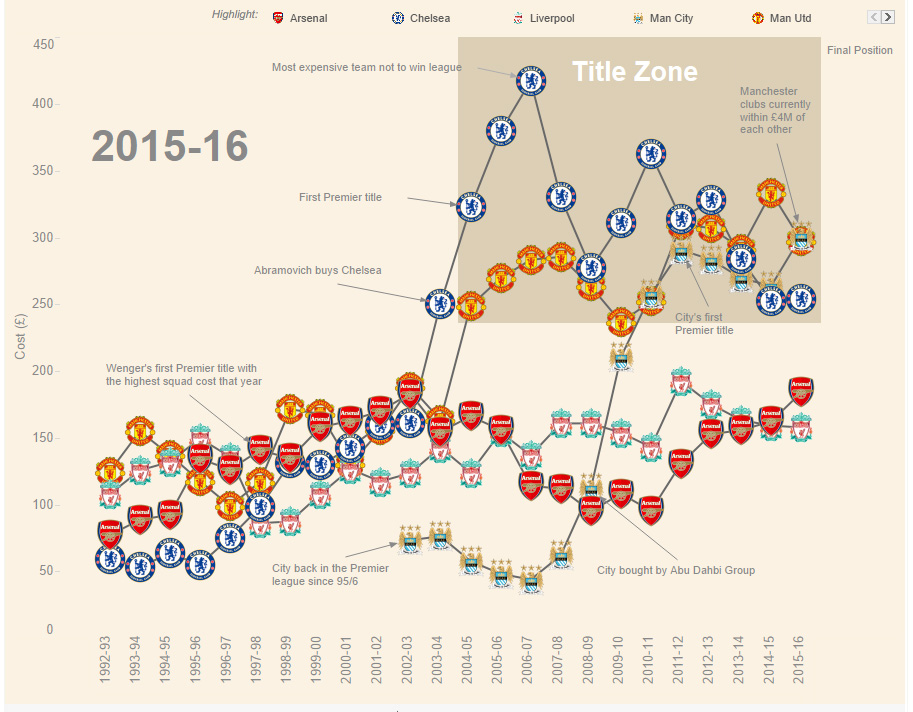

The following is an updated version of a graph that I first produced two seasons ago, this time recreated and updated by Robert Radburn in Tableau for the Data in Sport conference that we presented at earlier in the month. (Click on the link for the interactive version.) I was going to post it as a standalone reference point, but it fits with the gist of this article.

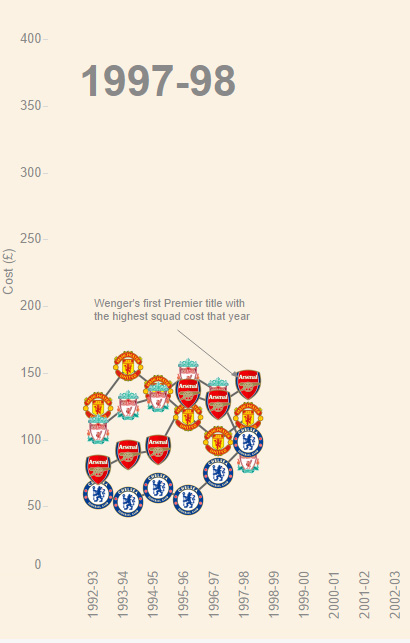

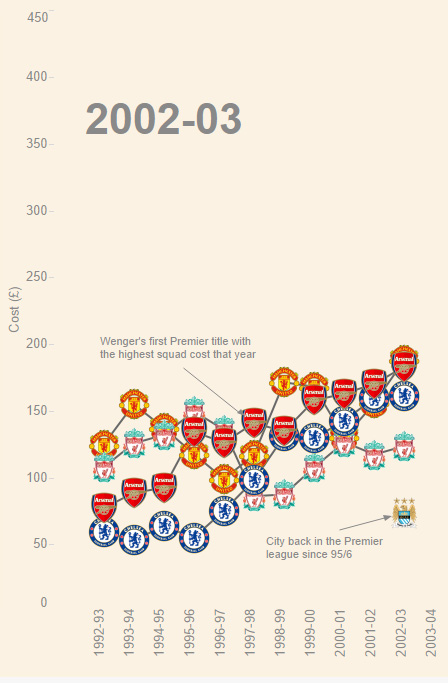

The full graph can look a little busy on first inspection, so I’ve shown how certain teams can be focused on with the other greyed out. And to start with I’ll introduce just the early years. The values for each club are their “£XIs” – the average cost of all XIs that season, adjusted with our Transfer Price Index inflation.

(Also, the full-size graphic is wider than our limited 500 pixel width, which may make it look a little messy – although the TTT revamp, which is currently underway behind the scenes, will address this in early 2016.)

There are essentially two distinct eras within the Premier League: pre- and- post-Abramovich. In the pre-Abramovich era the title was also always won by one of the biggest spenders – either Man United, Blackburn (not shown in order to stop graph getting too cluttered) and Arsenal. But their £XI often wasn’t much greater that that of Liverpool, Newcastle, Spurs and, during the Ranieri years, Chelsea.

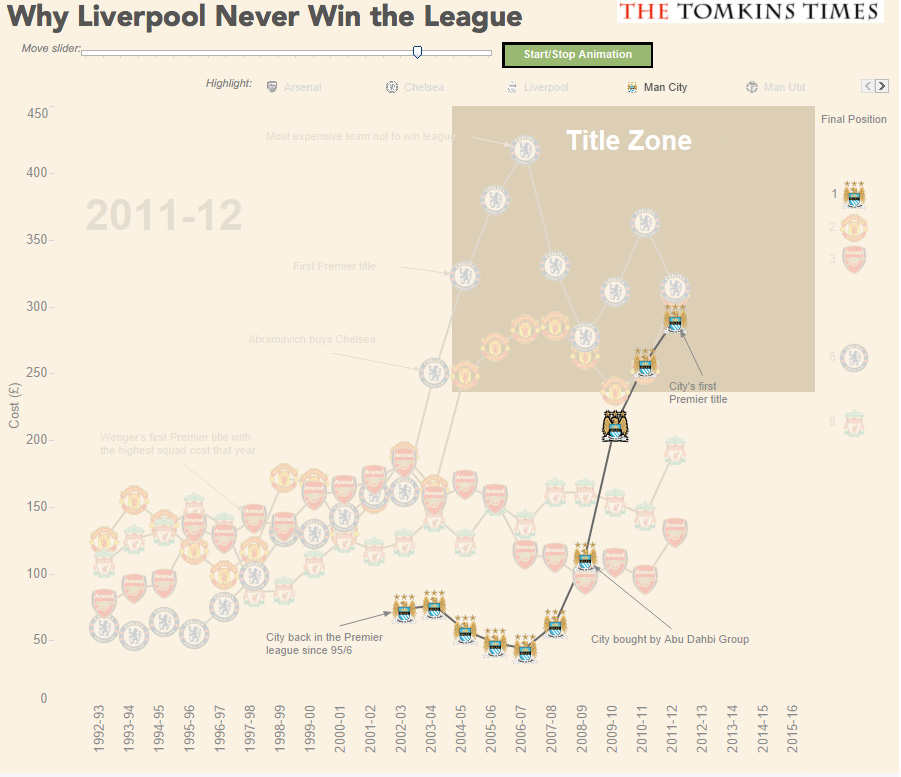

The post-Abramovich era showed how the title became the preserve of just two clubs before Man City arrived on the scene. That trio created the modern Title Zone.

The graphic shows how City joined the elite and helped push Liverpool out, and it also shows that Arsenal – whose teams were the most expensive when Arsene Wenger won two of his three titles – also fall well short of the elite three.

It also shows Arsenal pulling away from Liverpool this season, especially with the inclusion of both Alexis Sanchez and Mesut Ozil in the starting XI. (Arsenal only started winning trophies again when their £XI recovered after the years spent financing the Emirates stadium.)

(Click on the images to enlarge. Alternatively, click here for an animated version of the graphic.)

The Title Zone isn’t set in stone as a dictator of what will happen – but it’s a good indication of the kind of investment that brings success, based on the past 11 seasons. Until someone can think radically differently, it’s hard to see it changing.

Despite a fair amount of investment over the past couple of years, Liverpool’s figure is weakened by the short-to-long term absences of several big signings, whose 2015 transfer values are in excess of £20m: Henderson, Sturridge, Benteke and Firmino, with only one of the two expensive centre-backs (Sakho and Lovren) ever playing at any one time. Markovic is also loaned out (as is £16m Balotelli), and Joe Allen has fallen down the pecking order, and provide examples of where the spending perhaps wasn’t evenly distributed.

When we created the graph, over a month ago, Liverpool’s £XI was £157m – but since then (going into the Swansea game) it had dropped to £140m.

However, what I think would possibly be Klopp’s strongest XI – Mignolet, Moreno, Sakho, Skrtel, Clyne, Henderson, Lucas, Lallana, Coutinho, Sturridge and Firmino – would cost a fairly hefty £195m (in 2015 money).

If Milner squeezes out one of Lallana or Firmino it drops by almost £30m, whereas if Milner didn’t come into that XI, and Benteke played instead of Sturridge, the £XI could reach £207m – which is getting closer to the aforementioned Title Zone (a minimum of £236m); and probably looks not far off being a title-challenging team if everyone was on top form. It looks better still at the slightly cheaper version that includes Sturridge, but that depends on the striker being as good as he was before almost a year and a half out.

However, managers never get to field their best XIs, nor their costliest £XIs, over the course of the season. The law of averages means that weaker players come into the XI; and the costlier your squad is overall, the greater the chance (if not the guarantee) that you’ve assembled genuine strength in depth.

But Liverpool do have a glimmer of hope. Manchester City don’t have a world-class manager; just a very good (and likeable) one, with world-class resources. So they’re not invincible, and seem to pick up a fair few injuries to those handful of exceptional players who lift them to a whole other level.

Manchester United have a proven world-class manager, but whose best days may be in the past, and whose style doesn’t seem to fit with what the United fans want. They’re doing well enough, but remain far from fully convincing.

Chelsea have a world-class manager, but their £XI is no longer the runaway leader, in the way that it was first time around for Mourinho, when he so arrogantly bossed English football; it now only ranks 3rd. And they’re having a dismal campaign, perhaps having pushed too hard, with too little rotation, last year.

Arsenal still aren’t quite right, although they have an excellent first XI, and some really good squad players. But something seems to be lacking – part of it is the size of the £XI to match the Rich Three, part of it may be a softening in Wenger (and aspects of his team) over time. They also seem to regularly have the most injury problems.

Spurs are doing really well, and look set for a bright future, with a fairly young manager and up-and-coming squad. Having never contested a title in the modern era, it’s unlikely that, if they did, they’d handle the experience well enough (all title winners tend to have a “nearly” moment shortly before, where they choke – but learn). Top three would be a big achievement for the club with the 6th-biggest budget – although the problem with pushing on from there is that they’d then be expected to take the Champions League seriously, and a smaller squad suddenly has an even greater workload. (This is why I think Arsenal are continually stuck in a loop: good enough to qualify for the Champions League, and to do okay in it, but those extra high-pressure games take it out of a squad that isn’t as big as those of the Rich Three.)

Liverpool are perhaps the wildcard – having contested a title in the past two years, many of these players have that experience (even though some of the key stars have since left, quite a few remain). Unlike Spurs the Reds have a manager who has won major league titles, and reached a Champions League final; two things that Arsene Wenger can match, but not in the last nine seasons – whereas Klopp did so as recently as between 2011 and 2013. Maybe Klopp’s style, while fashionable, is also a bit more modern? (Or maybe Wenger’s undoubted wisdom will shine through.)

With Firmino able to play as a centre-forward – certainly in one system – Liverpool possibly have more striking depth than Spurs, City, United and Chelsea (who all seem surprisingly light in that area, with maybe only two senior strikers in many cases). However, it depends on whether Sturridge regains his old belief (and fitness), and if Benteke can be used effectively enough. (The loss of Ings, who would have been ideal for Klopp, perhaps from wide areas, is a blow here.) Arsenal probably have the most varied roster of strikers, but seem weak in other areas.

Liverpool are overflowing with no.10s, and have a fair few central midfielders, but as noted earlier, there isn’t much depth at full-back (certainly without Jon Flanagan, who has been out for 18 months), and there’s only one proper winger in the squad, in Jordon Ibe. That will limit Klopp’s ability to spring surprises, particularly at home. These are key reasons why I feel that, with an injury here or there, Liverpool could be derailed.

I also don’t think that Liverpool have a title-winning keeper, although if everyone else is special enough, a lesser keeper (by those high standards) can be ‘carried’. However, Liverpool don’t have that, and I don’t (yet) trust Mignolet to limit the mistakes that could take him into the really elite level. Many titles seem to be secured by outstanding keepers, who come to the fore when things get a bit nervy, whereas Mignolet himself gets the jitters. He has improved, but he’s still well below the likes of De Gea, Hart, Courtois and Cech, and possibly Lloris too.

I’m also not sure that Liverpool’s centre-backs are good enough, although Klopp’s system helps them more than Rodgers’ did. Skrtel is too inconsistent, and Sakho, while improving all the time as he enters the “proper” years for a centre-back (aged 25+), tends to not stay fit long enough.

Liverpool also lack genuine top-class match-winners (perhaps Coutinho and Sturridge aside), although the Reds have a good smattering of honest and fairly gifted talents, and a manager who puts the team before egos, which makes for a good marriage. Klopp is genuinely inspirational, but he will probably struggle at times as the squad limitations become clear.

Still, I’m excited about the rest of the season. And thinking about the title could ruin the fun ‘ride’ that we’re in for.

The key, for me, is to see real improvement, and then look at what Klopp can do in the transfer windows, to address weaker areas; and also, what young players he’ll bring through in the next year or two. Klopp has the talent, confidence and aura – and the basic building blocks – to assemble something special, but Liverpool may just flatter to deceive this season … before everything is put in place to be taken much more seriously.