By Paul Tomkins.

A couple of years ago, with the aid of Graeme Riley’s immense database, I devised the Transfer Price Index Coefficient (TPIC), as a means of measuring transfer success rates. Our work together with TPI – which converts all transfer fees to “current day money” with an index-based inflation model – led to so many possibilities beyond its initial aim, as it evens up the most expensive signings of, say, 1994 with 2003 and 2014; so that rather than £5m – which was the transfer record 20 years ago – you can ‘see’ it as a value that makes sense in today’s market. (Chris Sutton’s move to Blackburn now equates to £28.7m.)

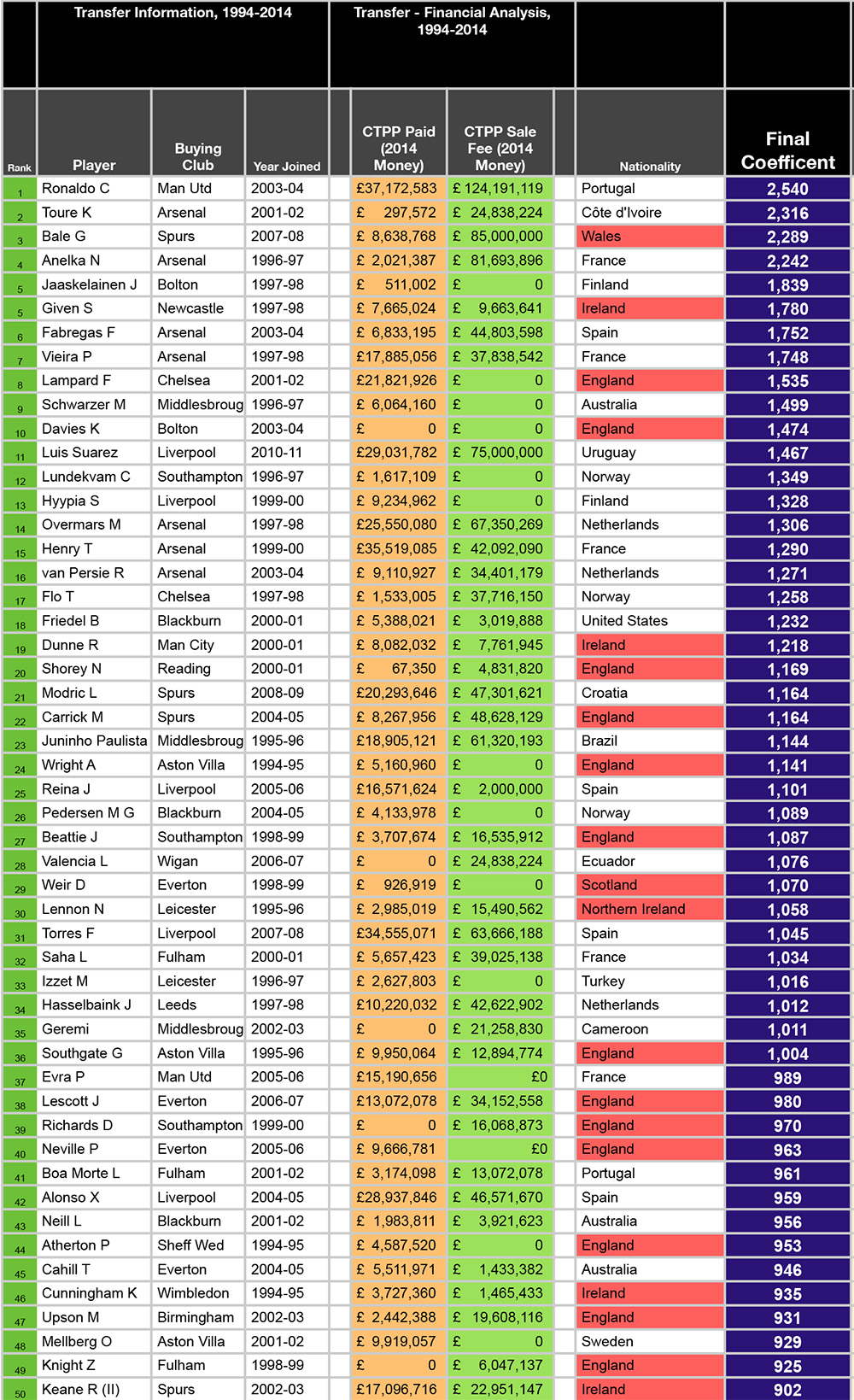

TPIC is calculated with the starting point of purchase and sale transfer fees (after TPI inflation has been applied) and then working in a score for the ‘profit margin’ as a percentage of the fee originally paid. It then adds points for the number of league starts a player makes, as well as points for the percentage of available games for which he is in the XI – i.e. was he a regular? – to produce an overall score; one which, in this case, ranks Cristiano Ronaldo’s move to Manchester United as the best bit of Premier League business over the past two decades.

If you look at the latest TPIC Top 50, more than half (54%) of the ‘best’ transfers between 1993 and 2014 had no prior experience of British and Irish football.

That means that over half of the ‘best’ buys in the past 21 years have been totally new to our game. Another two (4%) of those who had some prior experience were also foreigners (an Australian and an American, both goalkeepers), making for just 42% who represented England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Ireland, even though players from these regions make up the majority of all signings since 1993, albeit by a small margin, at 55% to 45%. (I believe that only 35% of current Premier League players are English, but I’ve counted all ‘home’ nations, plus Ireland, as the same, as the football culture, climate and main language are largely identical. And 10-20 years ago, most transfers still centred around these nationalities.)

Now, I’ve put inverted commas around the word ‘best’ because not every transfer in the database has reached its full potential. Both Tim Howard and Petr Cech are already in the top 50, but unless Chelsea’s Czech is sold in the next few days, both transfers have the potential to further improve their TPIC ranking; whereas the TPIC scores of the other 48 are all set in stone, as players who were both bought and sold by the same club. A big fee for Cech would see him safely into the top 20.

Joe Hart, just outside the top 50, is almost certain to break into it over the next couple of years, either through playing the games that will improve his TPIC score at a set rate, or through raising a sell-on fee, which will improve his score in relation to the size of City’s recoupment (the bigger the sell-on fee, the better it scores).

Ronaldo leads the way in the TPIC rankings courtesy of having cost £37.1m in today’s money – a lot, but not an outrageous amount – but been sold for a staggering £124.2m after inflation. This represents profit in excess of three times what was paid – a markup which actually happens quite a lot, but in this case, it amounted to over £87m. In between he made 157 Premier League starts, at a healthy 69% ratio for an attacking player. This all gives him a TPIC score of 2,540.

Ronaldo leads the way from Kolo Toure, whose spell at Arsenal came on the back of a tiny fee, following which he started a well-above-average 203 games at a 76% ratio; until being sold for £24.8m TPI, for a profit – and this is where he scores biggest – amounting to eighty-two times what was paid. (In any walk of life, if you can buy something and sell it for almost 100 times what you paid, you’re onto a winner.)

Very different players, who gain high TPIC scores in very different ways, but who can both be said to have been excellent deals. (And this is all about the deals: great signings, not necessarily great players.)

Completed Deals Only

As before, once I’d seen how everyone ranked I removed the players currently still at a club, to leave just the conclusive deals. Most ‘unsold’ players will see their scores improve, although as I also take into account the percentage of starts made, a couple of seasons on the bench or out on loan could actually harm their current score.

As an example, two years ago, when I first devised the TPIC, I predicted that Pepe Reina would soon be cemented within the top ten: he had eight or nine seasons ahead of him and if Liverpool did sell him, reports suggested that it would be for around £20m. But since then missed a season’s worth of football for his parent club whilst out on loan in Italy, and his estimated transfer value – which doesn’t form part of TPIC (as guessing at transfer values is too messy) – dropped from £20m to £2m when he finally moved to Bayern Munich this summer; a stark reminder of how quickly perceptions and valuations can change in football. As it stands, now that he has been sold and can take his place in the ‘cemented deals’ list, he is ranked 25th, the 5th-highest for a goalkeeper. Similarly, Petr Cech will easily enter the top 20 if he’s sold for £10m, but if he stays at Chelsea as a sub his score will start to diminish, until the point where he either regains his spot or is sold.

As before, I’ve excluded all trainees from the equation, as this is purely a study in transfer success and failure; so there’s no Steven Gerrard, Jamie Carragher, Paul Scholes or John Terry, who would otherwise be in the top 10, with Ashley Cole only appearing in the list once bought by Chelsea.

In total, 3,777 transfers have been analysed.

So, British is Best?

Four of the top five TPIC buys were foreigners arriving fresh on these shores – Ronaldo, Kolo Toure, Nicolas Anelka and Jussi Jaaskelainen – with the other being Gareth Bale, who moved to Spurs from Southampton.

Quite incredibly, three of the five were aged 18 or under when signed, with the other pair being 20 and 22 respectively. In today’s money they cost an average of £9.7m, but their sale fees come in at a whopping £63.4m apiece. The quintet started almost 1,000 Premier League games between them, but in the case of Ronaldo, Toure, Anelka and Bale, were sold for exceptional money whilst still young enough to command a big fee; while Jaaskelainen makes the top five having played an absolute ton of top-level games for Bolton at a 91% start ratio.

Flops

It’s harder to say what the worst signings are when including current players – which is another reason to exclude them from TPIC altogether – because someone like Mesut Ozil has a high price tag, hasn’t been sold and also hasn’t had the chance to play many games; after a year you’d put him down as a flop, but then Arsenal have had plenty of slow starters during Wenger’s time, such as Henry and Pires, with Bergkamp also taking a while to get going. Ozil may go on to be an outstanding player for the Gunners, but at £40m he won’t be the kind of amazing deal that Anelka or Vieira represented.

Then there’s someone like Sergio Aguero, whose inflated fee – of £56.8m TPI – is enormous, and who has missed quite a few games in a relatively short period at City; yet based on the kind of thing TPIC cannot fairly measure (goals, medals, etc*.) he’s been worth every penny.

(* I opted against finding a way to accommodate statistics like goals, because then you are heavily weighting the rankings against defenders and holding midfielders, or different kinds of attacking players, with holding midfielders again unfairly punished if you count clean sheets. And performance data rankings like those used by Who Scored are relatively new, and cannot be retrospectively applied by more than a handful of years – and for this to work, every player over the past 21 years has to be judged on equal terms. So, for me, TPIC works on the broad assumption that if you start a lot and/or a high percentage of Premier League games, you can be called a success. Equally, if you were cheap and sold for a fortune, the deal worked out. You end up with a lot of neutral deals – players who didn’t cost much and didn’t play much, and weren’t sold for much. But you get interesting cases like Romelu Lukaku, whose original fee at Chelsea rose by about £10m with inflation, to £29m; interestingly, Everton paid £28m for his this summer. He did next to nothing for Chelsea, but he didn’t leave them in debit. In an age of stockpiling young talent – which doesn’t seem fair – he was a sensible gamble, and the club more-or-less broke even on it.)

Removing current players – those bought but not yet sold – reduces the list to 3,062 transfers. A few weeks ago I wrote about how Chelsea ruined football, the thrust of which focused on how much more money they spent, above and beyond other clear big spenders of the modern era – such as Blackburn in the mid-’90s and Manchester City more recently. Chelsea’s spending between 2003 and 2007, in relative terms, dwarfs all other clubs.

Quite incredibly, the six worst TPIC signings are all Chelsea players: the harshly-included Michael Essien, followed by clear flops in Veron, Wright-Phillips and Mutu, half-flop Crespo, and über-flop Shevchenko. The average price of this sextet, with inflation added, is almost £60m.

Essien performed well but cost an eye-popping £71m in 2014 money, Crespo barely played – his appearance percentage drops due to a loan back to Italy – and Shevchenko, at £80.5m for just 30 starts over a number of seasons (also including loan spells abroad), is by quite some distance the worst signing of the Premier League era, with the only score to exceed -999; in his case, it’s -1,464. The most feared striker in Europe somehow became a lame duck.

If current players were included, Fernando Torres at Chelsea would rank the 2nd-worst, at -992. The most feared striker in Europe somehow became a lame duck. Unlike Shevchenko, Torres can improve his score, although Chelsea would need a decent sell-on fee, otherwise sitting on the bench will only further damage his TPIC rating. (Even so, he shouldn’t undertake Shevchenko for the wooden spoon.)

All of these players, bar Torres, were signed within the first three years of the Abramovich era, when paying £20m or £30m for a player was a real fortune; most clubs, including Liverpool, couldn’t even play half that. A decade on, £20m, while not cheap, is now a fairly common fee. Torres was a British record, but that now belongs to Angel Di Maria, as actual fees hit £60m.

The 7th-worst TPIC signing is Michael Owen to Newcastle, when moving from Real Madrid: he cost £47m TPI, was barely fit, and then left on a free. You can’t get much worse than that: failing as a deal in every sense. Meanwhile, Andy Carroll, his erstwhile strike partner on Tyneside, managed to scrape himself out of the bottom ten last summer due to a reasonable sell-on fee, when West Ham took him to Upton Park, to spare some of Liverpool’s blushes. It’s important to remember that he was ‘only’ the 15th-most expensive Premier League signing after the application of inflation, but even so, the £44.5m that equates to still makes most Reds wince.

For the purposes of this article I decided to remove those who were at the bottom of the TPIC rankings on account of incredible fees (followed by low or zero sell-on fees) where the deal could be justifiably called clear successes on the pitch (such as Essien, Dwight Yorke at United and £66m Didier Drogba at Chelsea). The worst 20 signings then comprised of 11 players (55%) who were new to England, and nine with prior experience of our football.

So, Foreigners Are Better?

So at the extremes – the outrageous successes and the undeniably expensive flops – there’s a slightly greater number of fresh imports. Which means the pros pretty much balance out with the cons when it comes to buying someone with prior experience of our football.

Given that 54% of the 3,062 transfers involve players already based in Britain and Ireland (or who’d played here before), it seems that there is zero evidence to suggest buying a player with prior ‘English football’ experience is necessary. There’s a slightly higher chance that you’ll get a real gem, and a slightly higher chance that you’ll get a costly flop; whereas, on average, Brits (or those with prior UK-based playing experience) will be slightly less remarkably good or bad.

Gareth Bale – once derided as a terrible flop – is the best purchase from within these shores, and even poor old Kevin Davies – whose purchase for Blackburn by Roy Hodgson remains one of the ten worst deals in the database – places 10th during his sterling service to Bolton. The same player, proving to be outstanding value on a free transfer, but a nightmare when saddled with a £27m price tag (in 2014 money). He’s the perfect example of how this judges the deals, not the players in question.

In many ways Jaaskelainen and Davies kept Bolton in the top division for over a decade. In today’s money the pair cost a combined £500,000 – less than two weeks wages for Wayne Rooney – yet between them started almost 900 Premier League matches. Bolton join Arsenal as the only team with more than one player in the TPIC top ten. (Liverpool, with the signings of Suarez at 11th and Hyypia at 13th, just miss out; Reina, Torres and Alonso all make the top 50.)

If you look at those in the database with the highest number of starts for one club between 1993 and 2014, only 19 (38%) had no previous experience of British and Irish football. Most of those who play 500 Premier League matches will be of British origin. So it seems that you’re likely to get a greater number of appearances following a domestic purchase, but that could be because home-grown players are likely to spend their entire careers in English football, whereas if you purchase and Italian or Spaniard he is likely to want to return home at some point. Big clubs would rather keep their players than sell to a direct competitor, but will be happier to sell to Real Madrid or Barcelona.

Perhaps Premier League clubs buying from these shores helps with the initial acclimatisation – logic tells us that it must be hard to move to a new country, especially if there are language issues – but it’s still hard to know why physically strong, world-class players like Andriy Shevchenko and Juan Seba Veron failed to do well in our game but will-o’-the-wisps like Luka Modric, Juninho and Philippe Coutinho settled in.

So will Adam Lallana do better than Lazar Markovic because he’s used to our game? What I would say is that, with both men costing c.£20m, I wouldn’t favour Lallana based purely on his time at Southampton. In one against one comparisons, it depends on the individuals in question, and vagaries, such as luck with injuries.

I would, however, conclude that “he’s used to our game” is fairly useless as an argument in favour of signing any given player … And yet, of course, I’ll probably still find myself using it.