By Paul Tomkins.

While it’s not a long way from being a mathematical impossibility, Liverpool – whose home performances have often been simply sensational – can’t, in my opinion, win the league this season. To even have suggested it could be possible at the start of the campaign would have seen men in white coats banging at the door.

Liverpool have the best player in the country in Luis Suarez – whose brilliance helped tear Arsenal to yellow ribbons – and several other excellent attacking performers. But for being overshadowed by Suarez, Daniel Sturridge, whose goalscoring rate eclipses Torres at his best, would be talked of in more reverential terms, while Sterling is adding goals to his rapidly improving all-round game. It’s the most exciting Liverpool side I’ve seen in a very long time.

The Reds have a very good young manager, and are definitely heading in the right direction, with the annihilation of Arsenal one of those games that would be worthy of its own DVD, if the club did that kind of thing. If the title was awarded on attacking flair, it would be a tug of war between City and Liverpool. But of course, it’s not that simple.

In some ways talk of the title could obscure just what a good job Brendan Rodgers and his players have done to get to this position at this stage, because falling short, as I feel they inevitably will, will then be seen as a failing, rather than a great effort.

People will then look at moments like Kolo Toure’s brain-fart at West Brom and think of what those two extra points could have done. And yet every team will have its ‘if only’ moments, and every club will have games where points seem needlessly dropped when viewed retrospectively. Everyone can look back on their own team’s missed opportunities, ignoring those of their rivals. Maybe if Liverpool beat West Brom they’d have been overconfident (or less hungry) against Arsenal. Who knows?

People will also bemoan Liverpool’s transfer window failings, and it’s clear that at least one new player should have been successfully added, with aspects of the process botched. But the team’s two best performances of the season have come since the window closed, and those whose places might have been in jeopardy by the arrival of a new winger – Sterling and Coutinho – have excelled. (Still, cover would have been nice.)

Nothing follows a predetermined script, but I think there are too many firsts that need to be created, and/or trends overcome, in order for the Reds to land a 19th league title this season.

Some of these are as follows.

Lack of a world-class manager

It’s fair to say that Brendan Rodgers’ star is rapidly ascending, but even allowing for the slipperiness of the term, he’s certainly not ‘world-class’ (yet). He’s not used to winning trophies; after all, he hasn’t won any. Everyone has to start somewhere, but it’s asking too much to expect him to excel at something he’s never experienced before, and being in a proper title race creates new pressures. It may be possible in more meritocratic leagues, but it’s highly unlikely here, due to the way billionaire benefactors have bedded in.

Too often this season (and indeed last season) Liverpool have frequently failed when most expected to win. In some ways that’s to be expected. Previous talk of title contention led to surprise draws and defeats. The manager, and the players, have to acclimatise, and this season, for me, is about getting used to the pressure of higher expectations.

To expect Liverpool to go from last season’s hit-and-miss to title-winning consistency in 12 months is unrealistic. Rise too fast and you’ll get the bends. On paper, the best XI compares well with the big spenders and title contenders. But the Reds’ squad lacks experience and depth. It’s not too shabby, but it’s not the deepest, either.

The increased investment in the Premier League has made it almost impossible for ‘rookie’ managers to clean up. I tend to focus on the Premier League era not because I think it’s when football was created, but because, combined with the advent of the Champions League, it’s when football became less fair. Prior to 1992, it seemed that almost anyone could get into the top three, and therefore have an outside chance of the title. And yet the last ‘shock’ top-three side was Norwich back in 1992/93, the first “new” season in the revamped top division, with Nottingham Forest in 1995 the only other possible contender, but they were still seen as quite a big club at the time.

The last surprise to finish 4th was almost a decade ago, with Everton in 2005 (Liverpool were, ahem, busy elsewhere), and the last big surprise package to reach the giddy heights of 5th was Ipswich, in 2001.

There’s too much money and too many top managers towards the top of the table to allow a really big surprise to happen now. It requires too many powerhouses to have bad seasons, when they all have the insurance of large squads.

Put Rodgers next to Alex Ferguson, Kenny Dalglish, Arsene Wenger, Jose Mourinho, Carlo Ancelotti and Roberto Mancini, at the time they won their first Premier League title, and the Ulsterman’s record pales. He is of course just starting out – and improving all the time – but as I said, rookies don’t win the Premier League, just as you don’t really get player-managers anymore. The landscape has changed.

All of those named above were experienced title-winners before lifting the Premier League trophy. So if Rodgers manages to bring the title to Liverpool in the next couple of years he’d be breaking a pattern that goes back more than two decades (and I don’t just mean for the club itself). It would be remarkable.

While the aforementioned Mancini is a divisive figure, his titles in Italy deserve respect (three times Champions with Inter, four domestic cups with three different clubs), as do Ferguson’s in Scotland (at a time when the league was stronger, and Aberdeen big underdogs). And Dalglish’s three titles with Liverpool – particularly the 1987/88 vintage, as he reshaped the side to wonderful effect to make it definitively his own – cannot be underrated.

Dalglish was perhaps ‘of his time’ (in that most people don’t see him as a modern great), but in 1995 he was hugely respected and feared, and the money Blackburn spent only put them level with United in terms of squad cost; Dalglish was the factor that helped them become winners. (See Pay As You Play for more details.)

The last non-world-class/previously successful manager to win the title in England? Howard Wilkinson, the year before the Premier League was formed.

Having said all this, right now Liverpool are deservedly in the top four, and I expect them to stay there. Thoughts of the title are just too premature for my liking, although it doesn’t hurt to dream – and, of course, aim high. The only problem is if people start playing the blame game if the Reds ‘only’ come 4th. But of course, if Liverpool did somehow beat the odds to land the title, that would elevate Rodgers to legendary status; because the Reds’ next title, whenever and however it comes, will be incredibly significant.

World-class funds

Titles are now only won by the clubs with übersquads. When adjusted for TPI inflation, last season’s top three had (and still have) squads and XIs twice as expensive as anyone else’s. Think about that for a minute.

These are three financial powerhouses, one built on success and good timing (United’s titles coinciding with the influx of big money to football), and two built on the greenbacks of billionaires. All three have had their issues at times this season, and United’s look too severe to overcome (although maybe they should try crossing the ball? Has anyone suggested that to David Moyes?).

But they all have big squads, and that tends to help as the spring rolls around. As it happens, Chelsea, who, with inflation, still have the costliest squad, and the costliest average XI (ignore Mourinho’s little horseshit), are top of the pile.

In any given season you tend to find at least one club under-performs in relation to its squad/£XI cost. (£XI being the average cost over 38 games, with inflation applied.) Liverpool in 1993 and 1994, Newcastle in the late ‘90s, Blackburn in 1999, Man City in 2009, plus Chelsea and Liverpool in 2012, are all examples of heavy underperformance in the Premier League era.

(Aside: I’ve also written about the effect that reaching two cup finals in a season can have on league form, if a squad isn’t near-perfect, but that’s another story. I would however say that it played some part in Chelsea and Liverpool having such poor league form in 2011/12, with their resources stretched. I’d also say one run to a cup final for a smaller club can have a negative impact, as does the following season’s participation in the Europa League.)

Overall, however, you don’t ever find the top three most expensive sides – the “rich three” – all outside the top three. (The rich three currently sit 1st, 3rd and 7th.)

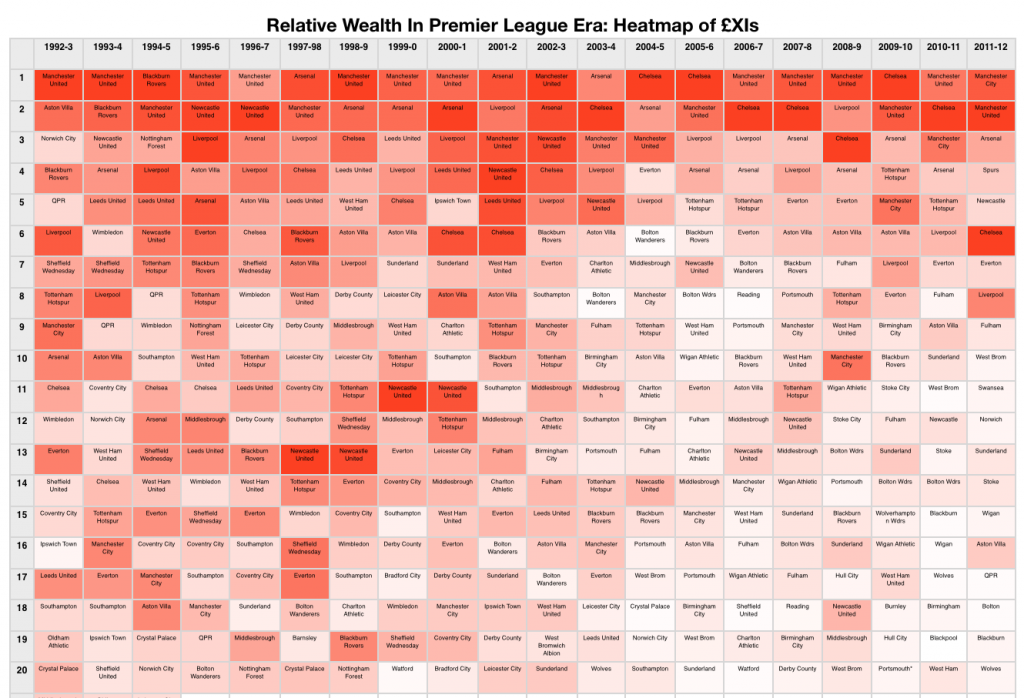

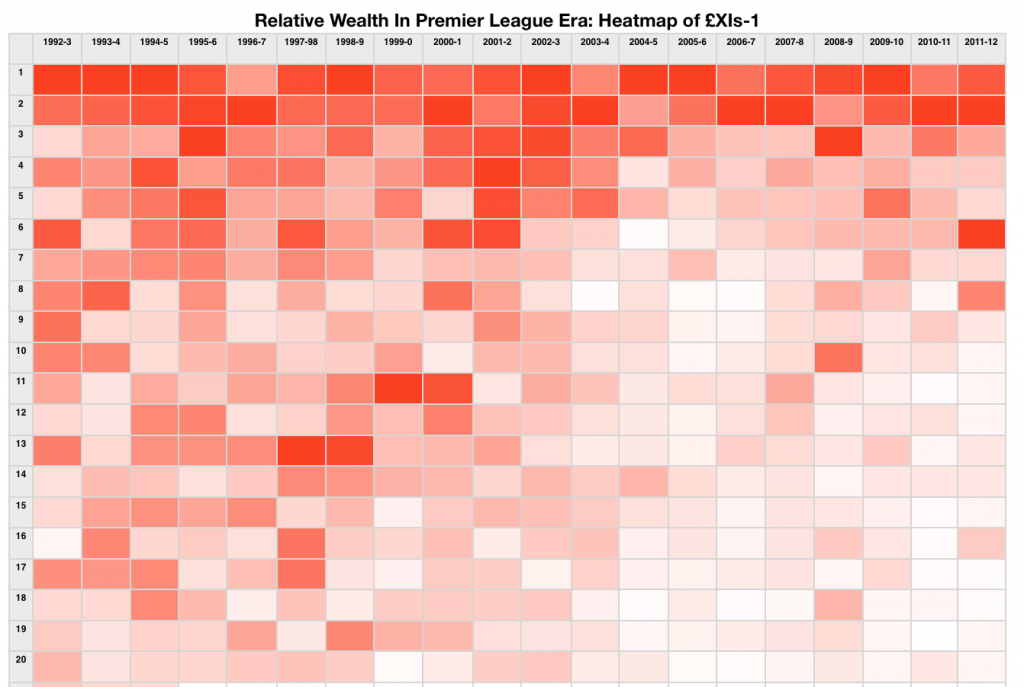

If you look at the following heatmaps, which I’ve updated from Pay As You Play (with the addition of two more seasons), you will see the strong correlation between the average cost of each £XI and its finishing position. There are two versions of the heat map below, the top one with the club names (the ‘ink’ of which can distort the sense of shading), and the one below without names, which just shows the results in their purest form.

It’s clear that overall, the wealth is concentrated to a small number of clubs, and those clubs finish higher up the table. Since the turn of the millennium, the gap has widened (notice the lack of variety in the shading on the right-hand side), making the league table far more predictable. Starting at the turn of of the millennium, if you were to blend all the reds together along each horizontal line, the shading would be darkest with the team finishing 1st, and lighten in steps all the way down to 10th place. Only then would you find a bit of a jumble. On average you get what you pay for.

I’ve never been convinced that Arsenal could win the title this year, even before Liverpool tore them to pieces, as their squad is too thin; too cheap. But if they do win it, or if Rodgers achieves the almost impossible, I’ll doff my cap to an incredible achievement.

The need to have finished in the top three the seasons before

Prior to the formation of the Premier League, teams could jump from 7th to the title. Teams could even jump from the division below to the title. The wealth was far more evenly spread around, and all teams had some kind of chance. Yet in the Premier League era, no-one has jumped from outside the top three to the title. The champions were either successfully defending their crown, or had gone fairly close the year before.

Also, “first-time” winners after the format of the division was changed have always had to go very close to acclimatise. United were runners-up in 1992, Blackburn finished 2nd in 1994, Arsenal were 3rd (but joint-2nd on points) in 1997, Chelsea ended as runners-up in 2004, and Manchester City, like Arsenal 14 years earlier, were joint-2nd on points in 2011. Go close, learn what it takes, then come back stronger. It doesn’t mean finishing 2nd gets you the title the next season, as lots can go wrong (as Liverpool fans know only too well), but it seems an important base camp.

Rather than a tilt at the title, this could be Liverpool’s chance to gain some vital experience. Even then, Liverpool have to overcome a lot of long odds just to finish 2nd. And although getting into the top four allows you to attract better players, for a better attempt next year, you do have the challenge of a greater number of tough games in a season. Once in the Champions League you need a mega-squad to compete on all fronts.

An unfortunate age

Young teams don’t win the league. So in a way, Alan Hansen was right. It’s no coincidence that in 1996 the Man United youngsters the pundit referred to on Match of the Day were surrounded by half a dozen senior pros. Young players have always played parts in winning trophies; but young sides are a different matter entirely.

Having said that, roughly one in four of the Premier League-era champions registered an average age below or equal to Liverpool’s current average age of 26.1. So this point is not an impossibility; just that almost 75% of title-winning teams are older than Rodgers’ Reds.

Right now, Chelsea are a full two years older, at 28.1 – showing that Mourinho is talking nonsense about his “young” side – while United average out at 27.1, City 27.9 and Arsenal at 26.7. Liverpool therefore have the youngest side in the top four, so it would be a big ask to expect them to win the title; particularly with so few players used to the experience. By contrast, Chelsea have loads of players who’ve been there and done it.

The one-nil

Right now, Liverpool can’t grind out the 1-0 wins that seem necessary to land the title (although this is merely empirical evidence). Of course, if you win all 38 games 5-0, then you don’t need to grind anything out. However, the law of averages suggests you will encounter quite a few tight games, where the odd goal (at either end) makes the difference.

Remember, a clean sheet is worth more points than a game in which you score. It seems almost paradoxical, but statistics show that the average number of points taken when keeping a clean sheet is higher than when a team scores a goal.

You can never lose if you keep a clean sheet, guaranteeing a minimum of a point, but you can score three and still get beat 5-3, as Stoke did to Liverpool. It’s great that the Reds are scoring so many, but it seems that titles are usually won with quite a few 1-0 wins along the way. If Liverpool don’t outscore teams then, based on this season so far, the defence isn’t going to uphold its end of the bargain.

Rodgers’ side are ahead of schedule, in terms of overall progress, but the defending isn’t yet good enough. Of course, it hasn’t helped that the first choice back four has had so many injuries, but equally, in terms of making a serious title bid, it doesn’t look like they’ll all be fit enough – and then playing without any rustiness – soon enough.

Remember, Manchester City and Liverpool have been the best attacking sides by far this season, with goal tallies into the 60s already, and yet they sit 3rd and 4th. Chelsea and Arsenal, both only in the 40s for goals, have kept more clean sheets, and they sit 1st and 2nd.

We’ve marvelled at the incredible attacking play by the sides fielded by Pellegrini and Rodgers, yet neither are in double figures for clean sheets; Arsenal and Chelsea both have 11. Is that why they have more points? Perhaps. (Although West Ham have the most clean sheets, with 12. They’re just a bit shit otherwise.

As observers we get seduced by great forward play – and it’s lovely to watch – but the ability to shut up shop is often more important, as long as you don’t sacrifice the ability to attack.

Conclusions

These are not random superstitions, like having a Scottish player with a moustache, or someone with ginger hair, in order to win the title. These a precedents with meaning, although on their own they don’t decide the conclusion to a season, and there is always the chance of an outlier or an exception to the rule.

Perhaps there are also examples that I have missed which counter what I’ve posited in this piece. (I’m tempted to add that the top three might suffer some Champions League hangovers once the knockout stage gets underway, but again, it’s a big ask to expect all three to do so.)

Could a side as young as this Liverpool one win the title? It’s not unheard of. Could a rookie manager make his first major trophy the Premier League crown? It’s not totally impossible. Could a team jump from 7th to 1st? In theory, if not in recent practice. Could a team win the title without keeping many clean sheets? Maybe. Could a team jump from 4th after 25 games to 1st, making up ground on not one but three teams? Again, perhaps.

But could a young, relatively inexpensive side with a rookie manager jump from 7th to 1st (and from 4th to 1st after 25 games) without being able to keep many clean sheets? Alas, it’s very, very unlikely.

All we can ask for is significant improvement on last season, and to enjoy the special football on display. Anything else is a bonus.