By TTT subscriber James Keen (jimtheoracle).

Football is a folk game in the truest sense of the word; it is of the people, by the people and for the people. Therein resides its power and longevity. The Victorians lay claim to codifying and defining the sport but the game itself has existed in some form or another all over the world for centuries. The Romans and ancient Greeks played a ball game with their feet, as did the Chinese; indeed the practice of Cujo (literally kick-ball) dates back to 1BC. There are variations in most cultures that are region-specific and as different from each other as football is to rugby. There seems to be something enduring and fascinating across the world about these team ball-games played with the feet. However, the game in England evolved from games that involved neighbouring towns and villages attempting to move a ball to a specific geographical location, the balls were usually carried and involved an unlimited amount of participants and resembled localised riots rather than a hobby or pastime. Injuries, deaths and huge amounts of civil disturbance were the result and as a consequence the high lords attempted to ban this unruly and rough folk game from existing; King Edward 3rd outlawed it in a proclamation in 1363. But the games survived.

The game seems to have always existed alongside traditional working people’s pastimes; folk music, dancing, brewing and craft activities. Like those practices there is a very protective force of opinion that tries to discourage and outlaw the capitalisation and monetisation of these pastimes. These things are derived from the folk and many believe that they should remain as an oral history and to exist as a time capsule and a reminder of where we came from. A window into the nation’s origins, even its soul. Folk dancing and music have largely remained intact, interestingly due to the Victorian and Edwardian composers who collected the traditional tunes and wrote them down, Cecil Sharp being the most important. This dispensed with the oral traditions that established them, but as a result it’s possible to find pubs all over the country that have regular music nights where people will bring their instruments for an ad hoc performance to perform, meet and learn new tunes. Traditional games also survive through the pub culture in this country. Furthermore the games, dances and tunes vary greatly from region to region. The Victorian obsession for organisation and order is vitally important in ensuring these traditions have survived.

It was the same with football; the game varied around the country and the rules differed slightly depending on the development of the game and the local opinions and needs. In the mid-1800s the Victorian public schools defined and locked down one game and this became association football. This, in a relatively unaltered form is the game that we all play today. The folk games were largely lost and football as we know it took over as the only form of the game. Despite the money and help from the upper classes football’s roots are seen as being still firmly planted within the mindset of the folk games, as a result the desire to protect the traditions and history of the game survive, despite the fact that the codifying and organisation of the game required money and wealth to bring them to fruition. The game is still squeamish about the influx of money and outsiders coming into the game. There has always been a strange dichotomy in football – it has always required rich men to pay for it but for it to be seen as encapsulating the working man’s struggle it would need to be subject to tight constriction based upon this idealism. In fact the game was popularised amoungst the public schools as a means to nurture young men with the right moral backbone and was an attempt to curtail masturbation by encouraging young men to be physical with each other and maintain their stiff (and heavily mustachioed) upper lips.

Liverpool are perhaps as wilfully traditional club as any in English football; they play in a traditional Victorian ground surrounded by very traditional terraced housing. Since the last title was won in the early nineties the club has been very slow to modernise, perhaps because of fear of how the fan base and the wider football culture would receive those changes. In the last two years the club has been dragged into the modern world. The new owners and managers are attempting to maximise profits and place the club back where its stature within the game suggests it should be. But has Liverpool now got so far away from Shankly that it doesn’t know who it is anymore?

Football is discussed and debated perhaps more than any other subject in Britain today. The press coverage and saturation coverage of all media is perhaps out of proportion with its relative importance. But the game fascinates millions. It is felt that there is a tradition of football in this country and there are quite narrow ideas about what football is and should be. There are often discussions about football selling its soul or losing its identity, despite the association of football having being established by the gentry.

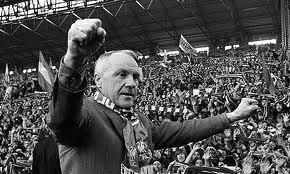

But what does that perceived loss of soul mean? Liverpool are the most successful team in English football; the club’s first league title was over 100 years ago, and in that time the club is said to have developed the Liverpool Way, a certain way of doing things. A lot of this originated in Bill Shankly’s era, and can be traced back to his remodelling of the club in his image in the 1960’s. To many Liverpool fans and observers, the soul of Liverpool is the one created by this man and shouldn’t be tampered with.

One of the great moral dilemmas in the last few years has been the move away from recognisable figures and the tearing up of the method that was established in the boot room. But the boot room has been gone for 20 years and the realities of modern football are far removed from Shankly’s day; it is a different game. In the same way the codified game was unrecognisable to the game of the folk, so the organisation of clubs and the game is unrecognisable to the fairly basic set-up that Shankly knew and innovated within. Crucially, the game itself is unchanged and the soulfulness of the game comes not from the vicious business acuity of the clubs but the recognition that once on the pitch players and teams are judged in much the same way that they always have been. There is the link to the origins of the codified game. The money doesn’t matter and for 90 minutes all that matters is the physical ability and game intelligence of the 22 players, and for that Reverend Thring would have approved. It appears the soul of the game (if not the hoopla around it) is largely intact.

FSG have owned Liverpool football club for nearly two years. They came to the city and club like they did the sport itself, with no previous knowledge or experience. Despite confidence in their own ability to make decisions and run large, internationally-famous sports teams, the first round of appointments they made was deemed either not right or not in keeping with their ideas for the club’s future. We were told or have at least inferred that they wanted to change the club into a young dynamic organisation that would challenge preconceived ideas, play attractive passing football and take us back to being Shanks’s invincible machine. Roy Hodgson did not [remotely -Ed] fit that template and his awful results did for him. Kenny was a temporary measure that was made permanent, but was still not what they had in mind from the beginning of their tenure. After Kenny’s disappointing league campaign, the Americans demonstrated the ruthlessness necessary to do the job and sacked him. Just another managerial casualty.

Except it wasn’t. They sacked the one living man who is revered by all Liverpool fans. He is one of the greatest British players of all time and one of the greatest British managers of all time. He is loved for his football and his compassionate support of an entire city grief stricken after Hillsborough. He is regularly described as the soul of the club, our own JoeP once described him as “literally a living saint”. As a Liverpool fan it is hard to disagree. He is said to embody everything that makes the club great and what may make us great again. He himself refers to doing things the way we have always done them, the Liverpool way, being true and honest and not worrying about what the outside thinks of us. When they sacked Kenny, a lot of fans took to the Internet to decry the death of the club, there was a significant period of mourning. This wasn’t just another managerial casualty because this wasn’t just another manager or man. In retrospect FSG should probably have let Kenny go after the end of his caretaker stint, by giving him the job permanently they opened themselves up to having to get rid of him at some point, and that was always going to be a significantly large can of worms.

In the wake of Kenny Dalglish leaving his beloved Liverpool for probably the final time, there was understandably a massive emotional reaction from the fan base. The supporters went through a period of soul-searching and there was significant concern that the club had lost a part of its identity, that some of its essence had been lost. The soul of the club was in jeopardy. We pride ourselves on being different to other fans; did this mean we were now the same as everyone else? The very fact that this debate was taking place suggests that we continue to be unique in our desire to remain Liverpool and in our respect for our history. Kenny is often said to embody the soul or essence of Liverpool Football Club, that he is an icon in the literal religious sense and that he provides a priceless link between past success and history and the potential future of the team and club.

As luck would have it, FSG are impressed by impressive people and Brendan Rogers has so far been impressive enough (without a ball having been kicked of course) to assuage some of the anger after Kenny’s sacking. But the club is now in a unique position in its history. We are genuinely at year zero; the past is just that now. Perhaps that was FSG’s intention all along, perhaps they felt our reliance on what went before had become a millstone. Perhaps this complete cut from what we have done before was deliberate. This is going some way to creating the dynamic modern organisation they envisaged when they took over. But we should be under no illusions that it is new, with little or no link to what went before.

So is it different now? Has it lost its soul? What is the soul of our football club anyway? How is it manifested? Does it exist outside of the minds of the fans? And are we using it as a euphemism for historical success?

The soul is clearly not reliant on individuals; there are no links at the club now that directly connect us to the boot room, which was bulldozed incidentally to make the media room bigger – rather neat metaphor that seems to encapsulate the changing environment that Liverpool Football Club operates in.

Anfield is one of the iconic stadia of world football. It is not strikingly beautiful like the San Siro/Guiseppe Meazza or a vast cathedral like the Camp Nou. But it has a substance to it that other grounds seem to lack. It is said that New York is a very familiar place even to those who have never been there. Friends and family who have been tell me that it is a very strange experience because it is the setting of so many classic movies and TV shows that there is a sense that you have been there before. Anfield is a bit like that; football fans all over world have seen David Fairclough score against St. Etienne, Shankly waving to the Kop in his red shirt, Luis Garcia’s infamous ghost goal, all seen the Kop singing ‘You’LL Never Walk Alone’, they have all passed into Anfield legend and therefore into the lexicon of the game itself. As a result of the high level of success, Anfield is a stage that is very familiar to fans of many different clubs, home and abroad. It has various idiosyncrasies that are accepted in a way that it would be impossible to put in place now. “THIS IS ANFIELD” stares down at the players as they take to the pitch, not as an obnoxious or aggressive statement but as a challenge to the opposition and an acknowledgment that this is an historical venue. It is an acknowledgement of the history and stature of the club.

Anfield is perhaps the most old-fashioned of all the stadiums of the big European teams; to an extent this has been deliberate as there has always been a reluctance to close the doors on Anfield and open a new ground. This seems indicative of the staid and traditional nature of the support and the club. Many fans in the last ten years or so have become more open to the idea of knocking Anfield down and rebuilding, partly because it is viewed as the final piece in the puzzle of how to get Liverpool Football Club back to the summit of European and English football, but also partly because we can see that Arsenal lost their Victorian ground and replaced it with a huge modern cathedral of steel and glass and it appears to have not affected the club at all. The history of the club is still intact (although not as considerable as Liverpool), they are nevertheless the third team of English football, historically the best team in the capital. It can be done properly and it can be done sympathetically. It may even lighten the load of the red shirt somewhat.

So it must reside with the fans, although due to the delicate nature of the human body they too are recycled, eventually to be replaced by new people with new takes on the idea of Liverpool. The fan base literally changes over time; the club is one of the biggest names in world football, one of the most supported clubs in the world. There are fans across America and Asia who have a massive impact on the club financially and in terms of profile. When Shankly took over, Match of the Day was still a few years away. Now fans in foreign countries have greater access to watching Liverpool than we do in England. So the fan base has not only literally changed but the nature of it has changed. The scouser casuals in sports wear is an image closely identified with the club but it is also now an historical image too.

So if we accept that the soul does not reside with the staff, or the stadium, or even the fans, can there be a true path? If so, what is it? Can there be a Liverpool Way that transcends the club and all of us?

We are now in a new position that we have never been in before, off the map; here be dragons. There is no-one at the top of the club with any previous link to the club. We have finally broken away from the old idea of the boot room and Shankly’s influence. This has been very hard for the fans to accept but I can’t help thinking the great man would have had some sharp words for the idea that the club should live in the past and not modernise. He was a man who had formidable ideas about men and teams and behaviours and what he expected. But he also knew what it took to be the best and the innovation and constant change that that required. He was constant and consistent in his desire to gain ground that other people missed. He attempted to introduce diets to help the preparation of the players, famously insisting they eat a lot of steak. He employed the first Youth Development Officer in English football, when Tom Saunders was brought in in 1968. He was also one of the first exponents of what we would now call the squad system, making the point that he did not drop players he made changes, but only because he had a big group to pick from. He even carried a little book around to jot notes down in. Perhaps most striking was the training that his Liverpool side were subjected to; he did not believe in thrashing the players as soon as they reported for pre-season training, the programme was carefully designed to fill the five weeks until the first game, and in that time the players were carefully brought up to full match fitness. Crucially, all the exercises were done with a ball [as is now reported with Rodgers – ED], and with plenty of rest periods and carefully considered routines.

These are very recognisable modern managerial traits. Shankly was vocal about treating people with honesty and respect but he was not old-fashioned or reluctant to make difficult decisions. He was determined to win, to be the best and was willing to use any tool at his disposal to get there. Unfortunately, the club generally has forgotten that and relied on its past to a greater degree – perhaps too great? The first break came when David Moores sold the club, the ownership changed for the first time in years but Rick Parry remained at the club in one capacity or another. When Parry was finally forced out, Dalglish was there in the background. There he remained until the events of last month. In some respects we are where we should have been years ago. New owners, new executives and a new manager. We are hopeful of them being a dynamic new force in the club’s history. But we are now at a place where the history of the club does seem to weigh a little lighter than it has for a while.

Up until now there always seemed to be a desire to put any potential managers or executives into context by describing them in terms of the team or the city. Houllier was a teacher in Liverpool and this was how he was introduced to the fans. In an attempt to keep peace with the traditional elements of the club, new employees were lifelong fans or had Scouse connections in some way. But didn’t that indicate how insecure we were with our position in the world? The fans would point to Paisley, Fagan and Dalglish as proof that appointing from within was the way to go, but Souness, Evans and to a far smaller degree Dalglish proved that point redundant. The trick was (and has always been, in truth) finding the right man, not someone with impeccable Kop credentials. In the past these were the same men but it became apparent that that wouldn’t always be the case. Even Christian Purslow had a season ticket, for how long or how many matches he actually attended I can’t find, but here was this thing that identified him as one of us. He wasn’t. We have learnt over the last few years that some people get it, others can’t even see it. Purslow was firmly in the latter camp, season ticket or not.

I am interested in this subject because we are all confronted regularly with this idea of the Liverpool Way and we all nod sagely without ever really articulating what we mean. Do we mean the same thing? The Liverpool Way seems to me to be what we mean when we talk about the essence of the club, an almost indefinable behaviour. We know it when we see it but probably couldn’t define it in any meaningful way; I have tried and can’t capture it at all. Although I know Rafa had it and Roy didn’t, that is about the most concise way I can describe it – although that may be hard to understand, how could a foreigner have a better understanding of one of English football’s great institutions than a man who might seem at a glance to be steeped in the footballing traditions of these islands?

There needed to be a bit of Shanks in the men that followed him, but that doesn’t mean that the men coming subsequently have to have even heard of him. They don’t need to be able to quote him or even identify him in a picture. But they do need to conduct themselves in the right way, in a way that chimes with those beliefs and values. Respect, hard work and love for the city are a vital starting point.

As the club’s stature and success began to wane we began to sign unsuitable players, individuals that Shanks wouldn’t have looked twice at. I can imagine what he would have had to say about Ruddock, Dicks, Stewart, Collymore, Diouf, Konchesky or Poulsen. Football is cyclical and it was inevitable that our time would come to an end – that’s what happens to empires – but the (to coin a Fergie-ism if I may) big-time Charlies that were signed in the aftermath of Dalglish were partly responsible for the watering down of that tradition. It shouldn’t have happened; Souness is one of the best and most successful players ever to wear the shirt, he should have known he should have applied the club’s traditions. He didn’t or couldn’t, which should have been the first clue that the Liverpool Way does not necessarily have to come from within the club, that it is not self-sustaining.

After Graeme came Roy Evans, and a lovelier man you would never wish to meet. His team played aesthetically pure and beautiful football. They were also brittle and psychologically weak. They were dubbed ‘the spice boys’, too interested in the lifestyle, too interested in embracing the newfound wealth of the Premier League. And so a team that could have, should have won the league, didn’t. Houllier understood the importance to the club of teamwork and solidarity, but he was too defensive and too paranoid by the end. So it came to Benitez, the first man since Dalglish truly worthy to inherit Shanks’s team. He was unfortunate enough to be manager in the midst of the worst political storm the club could have envisaged in its worst nightmares.

Shankly is in many ways the most important figure in the history of the club. He created the modern Liverpool and helped nurture and grow the roots of what would eventually become the most successful side in Europe. Rather than look at the methods Shankly used, it is most important to do the job in the manner that Shankly did. It seems to me that the soul of the club will be intact as long as Shankly’s personality is still to be found here. Whether the team plays at Anfield or fully embraces sponsorship is largely irrelevant as long as those things are done for the benefit of the team on the pitch. It is worth remembering that Liverpool were the first English league side to have their club sponsor’s name on their shirt.

The game has not changed much from the game those Victorian schoolboys played. It is faster and more skilful now, but at its core it is still a game based around the creation and exploitation of space on the field, and that will never change. It goes without saying that we never want to be Chelsea but we never did. The club got to the summit by being innovative and progressive, that is what we must do now. Of course we must honour and respect what has gone before, but if the destination can be brought closer by doing something that has never been done before than so be it.

In Oscar Wilde’s ‘Portrait of Dorian Grey’, the eponymous character has a portrait painted when he is at his most beautiful and vows to never grow old and ugly. He then begins to live a most debauched life while he remains unharmed. The portrait, which is kept hidden in the attic, bares the scars Dorian avoids. The end point arrives when Dorian in a fit of guilt looks at his portrait and sees the true nature of his soul and slashes the picture, killing himself and finally revealing his true nature. The club has attempted to freeze time on its beautiful youth for too long, the portrait has been flaking and decaying for some time. Seemingly it has taken these outsiders to take us up to the attic and rather than slash Liverpool’s portrait, have it completely whitewashed and started again. The frame is the same and the canvas is the same, but unlike Dorian Grey’s portrait, perhaps it can be repainted.