The stadium is without doubt the biggest decision facing Fenway Sports Group. TTT subscriber and financial expert Ben Stoneman performs an in-depth cost benefit analysis on New Anfield. At almost 6,000 words in total, the first half of the piece is free to all to read, and the second half for subscribers only.

With Groundshare well and truly off the agenda and FSG’s stated preferred option of redeveloping Anfield far from certain, “New Anfield” seems more likely than ever before, if a stadium Naming Rights partner can be secured.

When it comes to the value of a naming rights deal, Liverpool will be looking at the following benchmarks:

- Arsenal made just £90m from selling shirt and stadium rights over 15 years in 2004 and have since acknowledged that they settled for less than £3m a season naming rights to ensure 50% of the cash up front.

- Manchester City, irrespective of how fair the value is and all of the controversy it has created, received £400m for a 10-year deal with Etihad this summer. This£40m a season covered shirt sponsorship, naming rights and “Etihad Campus”.

- The current global market leader for naming rights is the recent $400m, 20 year MetLife sponsorship of New Meadowlands, home of the NY Giants and NY Jets NFL teams.

Gillet & Hicks’ Anfield – pretty pictures, but never even close to being built

On the face of it, it seems like a terrible time to invest in such a large project. Countries around the world are currently in the midst of austerity programmes that are designed to rein in what is perceived to be excessive spending. Governments around the world are reducing outlay to balance their books, all in the hope that this will also somehow spur growth. Several disturbing parallels to these conditions, and how countries choose to react to them, can be made with events in the 1920s. Regardless, one of the industries hardest hit by the decreases in spending is construction. Investment in infrastructure has largely been put on hold until economic conditions improve. However, under UEFA Financial Fair Play (as previously examined on this site), costs related to investment in infrastructure are excluded from the break-even calculation rules. The cost of finance (i.e. the interest on any loans required to build the stadium) is also excluded from the break-even calculation. Yet once the stadium is built, any extra revenues will count in our favour towards the break-even calculation. It’s not really a surprise that so many have referred to the new stadium as “the game changer”.

In this article I will make the case that it makes great sense (from a financial, marketing and entertainment perspectives) to build a new stadium. I will then detail one of the largest problems that face the owners now and in the future (and give a quick economics lesson to demonstrate how to solve this problem). Finally, for fun I will offer a few ideas how the club could maximise these revenues while remaining as sensitive as possible to the current economic conditions in the city.

Current economic climate

The problem with the logic that now is a poor time to invest in any sort of infrastructure is that those very conditions are extremely favourable right now. That may sound counterintuitive if one listens to the news – or mistakenly equates a household’s spending with a government’s or corporation’s – but there are three main reasons behind this statement:

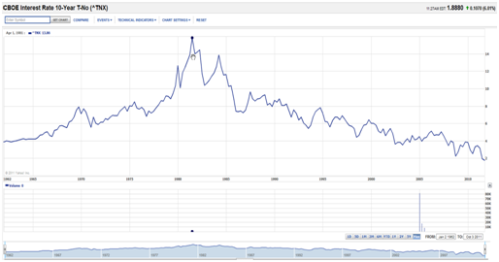

1) Interest rates are at historically low standards.

I know the mere mention of the word debt will send a chill down any supporter’s spine after the past few years, but it is highly unlikely that the owners will have £300 million to spend out of their own wallets. It is important to note that debt financing for something like a stadium is fundamentally different to the leveraged buyout the old regime used to buy the club.

The current rate for a 10-year Treasury note from the Central Bank of England is around 2%. The owners will not be able to borrow at the same rate as a federal government, but they will surely have access to lines of credit far beyond what the average person has. For a £250m loan, borrowing at a rate of 5% would yield annual interest payments of £12.5m. This may seem like a lot of money, but with the large increase in revenues a new stadium would bring, they are certainly not unmanageable.

2) The price of labour is comparatively cheap

Basic economic theory states there is an inverse relationship between unemployment and wages. As the unemployment rate rises, the wages needed to pay employees fall. The unemployment rate in Liverpool in 2010 was 12.2%. To compare, the rate in the North West was 8.0%; the national rate was 7.7%. For males aged 16-64 in Liverpool, the unemployment rate was a staggering 15%.

As I noted above, if decreases in infrastructure spending are a primary result of austerity, construction is one of the first industries that is affected. There are many skilled and well-trained architects, labourers, foremen and other workers who would be ready and willing to build the new stadium. Plus, from a fan’s perspective, how cool would it be to tell your grandchildren you helped build the new Anfield?

3) The price of building materials is cheap

This is probably the largest competitive advantage the club would have in building a new stadium now. Below is a graph showing the price of the Dow Jones Steel Index over the past five years:

I don’t want to suggest that Hicks and Gillett were right on anything – especially regarding their numerous broken promises on the stadium issue – but you can see that steel is much cheaper now than from 2007 through the collapse in late 2008. Growth in countries like China, India, Brazil, and throughout the Middle East over the next several years will lead to an increasing demand for building materials. The price for steel and other goods will increase as well. Also, it is worth noting that Henry made his fortune as a commodity trader.

There is no doubt that redeveloping Anfield would be cheaper now. However, there are two underlying costs to factor in should the club choose against building a new stadium. The lifespan of a stadium that is currently over 120 years old will eventually reach, and perhaps is already approaching, its limit. At that point, a new stadium would be built at a significantly higher cost. Additionally, closing down a stand or a portion of the stadium during the season to increase capacity could lower revenues. It is these two issues – matchday revenues and attendance versus capacity – which I will discuss next.

Match-day revenue

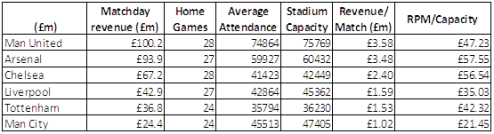

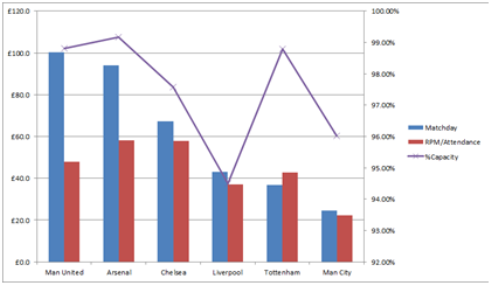

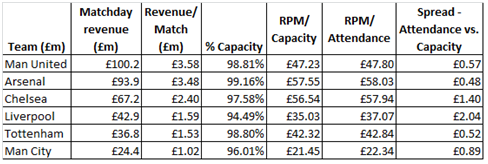

In March 2011, The Swiss Ramble meticulously detailed the finances of the top six clubs in the Premier League. He shows how Man United and Arsenal both generate £2m more than us in every single home game, and Chelsea £800k more. It should also be noted that his article uses data from 2009/10, the last season Liverpool were in the Champions League.

It is this Revenue Per Match (RPM) that Liverpool need to significantly increase to better compete with United, Chelsea and Arsenal. Their advantages lie in a combination of larger stadiums and, due to the cities they play in, the ability to charge much higher prices per ticket.

Knowing the markets the London and Manchester clubs operate in are very different from Liverpool, I decided to divide RPM by stadium capacity (the attendance and capacity figures were taken directly from the Premier League stats page). It is here you can begin to see the different playing field that the London and Manchester clubs are on.

For those interested, here is my spreadsheet with all of the data used in this report. The “Top20Euro_Financials” tab compares us to the other European teams in the Deloitte report.

Unfortunately, the money generated per seat is not the only issue facing the club as they look to increase matchday revenue. Liverpool, especially in comparison to other English clubs, simply does not fill up Anfield.

For those interested, here is my spreadsheet with all of the data used in this report. The “Top20Euro_Financials” tab compares us to the other European teams in the Deloitte report. Unfortunately, the money generated per seat is not the only issue facing the club as they look to increase matchday revenue. Liverpool, especially in comparison to other English clubs, simply does not fill up Anfield.

Attendance vs. Capacity

Anfield has been renowned for decades as a fortress, one of the most intimidating places to play for visiting clubs in all of Europe. It often seems that the fans in the stadium give the players an extra shot of energy, and our club is famous for the atmosphere on a European night.

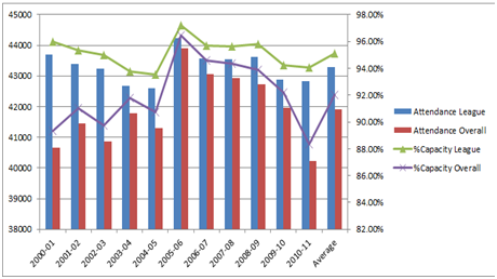

Despite this reputation, Liverpool has not maximised the number of tickets sold for home games for many years [although it’s worth noting that after four home league games, this season’s average attendance is a very impressive 44,932 – Ed]. This is true not just for last season during the Hodgson era, nor is it for Europa League or Carling Cup games. Even during our peak years of the past decade, winning the Champions League and ranked as the top club in Europe, Liverpool has fallen short of reaching capacity over a full season:

The blue bars show the average attendance for the nineteen league home games each season; the red bars include any European, FA and Carling Cup games as well. For those who find it easier to think in percentages, the green and purple lines indicate the per cent capacity of Anfield for league games and total games, respectively, each season. [Note that for the Champions League, UEFA mandates a certain number of rows around the perimeter are kept vacant so there is always a reduced capacity for CL games]

During the best year – 2005-06 – in terms of attendance over the past decade, we could not sell an average of 1,286 tickets for our league games (remember, we were fresh off being crowned European champions). In 2009-10, the season used for all of the financial figures in this piece, we were short an average of 2,633 tickets for each of our league games and a surprising 3,560 seats for the total 27 games we played that season. You can see a table of my figures, courtesy of lfchistory.net, that includes more information here.

It is easy to see why the club stated in the annual financial report that attendance versus capacity is one of the most critical drivers for financial performance (numbered page 2 of the document, page 4 of the PDF). The problem is only magnified in comparison to the other top English clubs:

The blue bar, which should be counted in millions of GBP, is total matchday revenue for the full 09-10 season; the red bar indicates the revenue per match for every ticket sold. Note that this figure is different than RPM/Capacity to highlight the difference for clubs that more closely sell out their matches (only league games to provide more accurate figures):

The UK clubs that maximize the capacity of their stadium have the lowest spread in that final column. To think of it another way, Liverpool must charge a premium of over £2 per ticket to make the same amount of money as they would if all seats were sold. Or, with that £2 premium and selling out all seats, the club could make an extra £2.46m per year. Compared to the other five teams listed, a lot of work has to be done.

The second half of this article is for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]