Paul Grech reviews Football Manager Stole My Life for TTT – and as it’s the busiest week of year for online sales, we’ve reproduced a few of his other book-related pieces, to help with decisions on Christmas presents.

For some LFC-related Xmas gifts, click here.

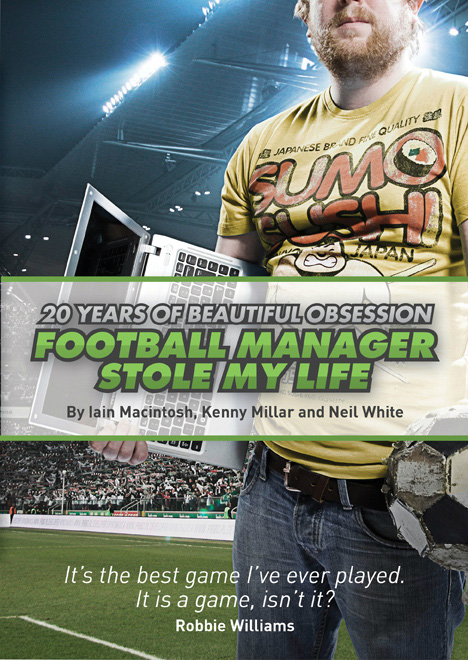

Football Manager Stole My Life

Given a choice of what game to buy when I got my first computer (a Sinclair ZX Spectrum 128K) I opted for Kevin Toms’ football manager. It was the same thing when a few years later I graduated to a Windows PC, only this time the game was Championship Manager.

This proves two things. The first is that, subliminally, I had already realised that I was more cut out for cerebral activities then physical ones.

Secondly, it proves that when this book talks about the addiction that this kind of management simulation can lead to, I know fully well what they mean.

And there is a lot of talk about the addiction that is normally associated with such games here. In fact there is a large number of personal experiences of users for whom the game had a significant impact. Some of these are entertaining but eventually they become repetitive talk of nights spent playing and obsessing over the game.

Much more interesting are their chats with some of the players who became in-game legends. Players like Cherno Samba and Nii Lamptey became famous when their potential was inflated making them must haves by those playing the game. In most cases, their actual career hasn’t been anywhere near as successful so there are those who aren’t too happy to be reminded that they haven’t done as well as some had expected them to.

Most however are delighted by their virtual-fame and they’re more than happy to talk about it. This leads to some very interesting stories which help give life to the book.

The same can be said about another feature of the book which is talking to the game’s creators about how it was developed. This in itself is a fascinating story that deals with the growing pains of a game that was perhaps far more successful than its developers ever dreamt it would be.

Yet the best parts of the book tend to be those penned by Iain Macintosh with his hilarious fictitious tale of Bobby Manager and also his interview with a psychologist over the effects of obsessing over a game like Football Manager.

Everything is very well knitted together to present a thoroughly enjoyable book; one with some lows but also some very prominent highs.

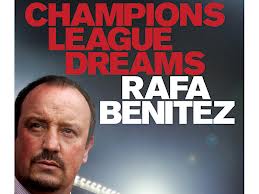

Champions League Dreams

(Review from October 2012)

The day after it was announced that Rafa Benitez had left Liverpool, I came across an acquaintance – a long time Liverpool fan – who surprised me by saying “don’t tell me you’re sad to see him go! Benitez ruined Liverpool.”

It was a reaction that took me aback. Naturally I was conscious that there were many fans who wanted to see the back of Benitez and thought that he wasn’t the one to take the club forward, but it had never occurred to me that there might be people who felt that he had ‘ruined’ Liverpool FC.

Two years have passed since his dismissal and fans – including a good portion of those who wanted him out – are looking much more positively at his time at the club. Time, and the failure to get anywhere near a Champions League spot in the meantime, has enhanced his reputation to the extent that when Kenny Dalglish was dismissed there were many who clamoured for his return.

If there is a positive side-effect of that demand not being met, it probably lies in the fact that he got to finish writing Champions League Dreams.

As the title suggests, the bulk of the focus of this book is on the Champions League and how Benitez managed to do so well in this competition. There are insights, explanations and tactical talks as he explains in detail every game that his team played. He explains how the much maligned zonal marking system was often, in fact, altered to man-mark individual players. And he explains in detail why he took certain decisions, the formation for the final against AC Milan in 2007 being the main one. It is all incredibly fascinating and a true learning experience.

Benitez also talks about the lead-up to certain decisions. One such instance is the decision to sign Fernando Torres after a list of strikers had been drawn up. Another deals with what led to the failure to sign Simao Sabrosa. Both put light on previously unknown details and there are plenty more such instances. Yet do not expect any criticism of the people that many feel let him down during his time at Liverpool – the likes of Hicks and Gillett or Christian Purslow – and although they do get mentioned it is often cursory. Nor does he talk about the split with Pako Ayesteran. The impression is that he feels that such matters have little place in a book about football.

Although unwittingly, he also highlights his own genius when, for instance, he explains that in 2005 he started the game against Juventus with the players instructed to adopt a tactical shape for the first few minutes and then changing it hoping to gain an advantage when his opponents didn’t react to that change.

Indeed, the overwhelming sensation at the end of this book is awe over Benitez’s management. Not just of games but of everything. At one stage he mentions his often publicised love of the game Stratego and how he spent a couple of days obsessively drawing up strategies on how to handle each situation so that he never lost another game. The thing is, that is how he handled every minute detail, looking at getting information or a strategic advantage.

When Liverpool beat Manchester United 4-1 at Old Trafford, he started telling any journalist who would listen a step-by-step guide on how to beat them in the hope that they would report it and some other manager would adopt the system, getting United to drop points.

That is how Benitez works, obsessively looking into each detail to see what can be done to improve it and gain an advantage. That is what comes out of Champions League Dreams, which is more of a manual of how a great manager works than a mere biography of his successes.

eBook Review of ‘Shankly: The Hard Road Back

It was an unfortunate piece of coincidence that on the weekend in which Bill Shankly would have turned ninety nine, results on the pitch brought up one of the worst periods during his tenure as Liverpool manager.

By picking up just one point out of a possible nine the current Liverpool team matched the results of Shankly’s 1962-63 side that also achieved such a total (the coincidences do not end there: on both occasions the point was achieved through a 2-2 draw with Manchester City); a total that every Liverpool side had bettered since.

The similarities, however, end there. When the league season kicked off in August of 1962, Liverpool were making a return to the top flight after an absence of eight seasons. The man who had taken Liverpool up was, of course, Bill Shankly after he had built a side capable of dominating the Second Division.

During the weeks leading to that first season back, Shankly had embarked in what was (and probably still is) an unusual venture: for fourteen weeks he had written a column on the Liverpool Echo going into incredible detail about how that team had been built and promotion achieved.

These columns have now been reproduced in a unique book that offers an insight into Shankly’s early Anfield days and the mind of the man who built the modern Liverpool.

Unearthed by The Kop Magazine, ‘Shankly: The Hard Road Back’ tells the story of how the great Scot turned the Reds’ fortunes around in his own words.

Published over a 14-week period in the summer of ‘62, Shankly revealed his Anfield battle-plan in unprecedented detail in the Football ECHO – revealing everything from his tactical thinking and transfer discussions in the boardroom to how he trained his players and sought out opponent’s weaknesses.

Indeed, hindsight proves just what a great visionary Shankly was. His belief in the importance of fitness extended beyond what was commonplace at the time. Training was split up so that each coach handled different groups to take into consideration different work loads and individual requirements. Similarly, every detail of the training routines was planned in advance to ensure that the players got the utmost benefit from the routine.

Shankly’s attention to detail – a trait of any successful manager – was such that before a game at Sunderland he tried to measure when the sun went down behind the goal to determine which was the best side of the ground to kick-off towards!

There are also glimpses of his legendary motivational abilities. When talking about the young players at the club he states that “I brought to Anfield a number of boys who attracted my attention as youngsters out of the ordinary”. You can imagine James McKenzie, Robert (Bobby) Graham, George Scott, Gordon Wallace, Philip Tinney and Tommy Smith reading those words and their self-belief going up by a couple of notches.

Of those players, two – Graham and Wallace – eventually enjoyed varying degrees of success in the first team whilst Smith went on to become a club legend. The investment of time and effort Shankly had put into the identification of these players paid off. Although he does not say so in the articles, a bit of subsequent research (such as this interview with George Scott) shows just what a personal interest he took in these players.

Yet these articles also hold evidence that even the great man sometimes got it wrong. One of the players he bought during the season was Jimmy Furnell. The goalkeeper was described by Shankly as a “player in whom I had been interested in for longer than this particular season” and his faith in him was such that he was immediately given the number 1 shirt which he retained till the end of the season.

Furnell, however, failed to live up to the expectations that Shankly had for him and midway through the following season he would be replaced by Tommy Lawrence.

Shankly: The Hard Road Back is only available as an e-book.

An Interview With Simon Kuper

Goals scored and conceded. Points won. Attendance figures. Up till a few years back those were practically the only statistics that made their way on to the football pages and in to the fans’ consciousness. Now it is a completely different story. Clubs employ teams of statistical analysts, journalists regularly quote passes made, fans look at heat maps of individual players and apps churn out an apparently endless stream of statistics. The shift in culture has been massive.

One who was at the forefront of this change was Simon Kuper, who in 2009 teamed up with Stefan Szymanski to write ” Why England Lose: And other curious phenomena explained” which was the first serious literary attempt at trying to determine the role and importance of statistics in football.

The second edition of that book – re-titled Soccernomics – came out this year with a whole host of new ideas examined. In their own way, these two editions reflect the culture change that has taken place. “In the first issue we didn’t talk a lot about match statistics but instead we used a lot of financial statistics and off-the pitch statistics. In the recent issue of the book, however, we have a whole chapter devoted to match statistics.” Kuper says. “That in itself shows the difference that has taken place in these past few years and how much match data has developed.”

“It is part of the general trend of football people becoming intelligent and less worried by numbers. Also they’ve seen the value of statistics in baseball and cycling. In particular they’ve seen how numbers have fuelled the success of British cycling which has made British football clubs more interested.”

For Liverpool that trend involved the appointment of Damien Comolli, which came thanks to the recommendation of Billy Beane, the star of Moneyball. Yet whilst Comolli was supposed to usher a new era of intelligent signings based on detailed analysis of statistics, he delivered what quite possibly is the biggest waste of a £100m transfer budget.

Kuper, however, is willing to be a bit more charitable to the Frenchman than the average Liverpool fan. “First of all, I’d say that Comolli got a couple of decision very right. He was correct to sell Torres for that sum of money and secondly he was right to buy Luis Suarez. So I think that Comolli did slightly better than a lot of people give him credit for.”

“The error, I think, was that the philosophy was to build a team with crosses. So you had Stewart Downing and Jordan Henderson brought in for their crosses and you also had Carroll bought because he is one of the best at heading the ball in from crosses. The problem is that crosses is a bad way of scoring goals. It isn’t as good as the short passing system of Barcelona and Arsenal, for instance – even if your players aren’t as good as Barcelona’s or Arsenal’s. The key fact is that not all data is the right data. We’re still in the learning stages of getting to know which data gives you the information you need.”

You’d imagine that Comolli’s failure would have put paid to any talk of Moneyball around Liverpool. Yet the phrase is still as commonly used as ever. What does Kuper – who makes frequent references to Moneyball in his own book – think is understood by this phrase? “People normally think of baseball where it was good way of getting undervalued players. It is what the Oakland As use to overcome their budget constraints. In football that hasn’t been successful and there hasn’t been a lot of success in statistics identifying the kind of players others don’t think are good enough.”

“Moneyball in football lies firstly in the physical side where statistics have been a huge source of progress. There are also dead ball situations. Statistics show that the best way to score from corners is by inswingers but a lot of traditional managers go for the outswingers. Similarly people should stop trying to score direct from a free kick and opt to pass it, even when it is from just outside the box. Statistics are also of great use in penalties, which can help you guess where a player will shoot. Stoke, for instance play a stats driven game for their throw ins.”

Statistics, therefore, will become increasingly more important for clubs yet not in the way that they were expected to be. “Statistics are more useful for dead balls then they are for buying. Only four or five clubs rely on statistics when it comes to decisions on who to buy. Others may use them to confirm certain beliefs but they’re more of a backup.”

Another area that Soccernomics deals with is the appointment of managers, with Kuper being quite critical of the rushed approach football clubs tends to take when appointing managers. It was an argument that will resonate with Liverpool fans given the negative reaction to the length of time it took FSG to choose a replacement for Kenny Dalglish.

“It was the right decision. Absolutely. I don’t understand why you need a manager next week. Why when you’ve got other people at the club managing things and you can keep functioning without the manager? It is an important decision and you should take your time to pick the right man. Look at Arsenal who took their time in appointing Arsene Wenger but ultimately chose the right man for them.”

One thing that Liverpool did change during the summer was scrap the notion of appointing a Director of Football. Again, Kuper approves.

“In football previously you had the manager making the decision and then you had someone like Comolli coming in with the decision. So the decision on transfers shifts from the manager to the technical director – but you’ve still got only got one person, or perhaps two people, making that decision. The problem is that two still is too few people to make a decision. It is better to have a group of people going over the decisions and debating them – “what about this factor or what about that”. The more opinions you have the better and more reasoned the decision you ultimately take.”

Encouragingly, this seems to be the approach that Liverpool will be taking where, although Rodgers will have the final say, transfers will be debated about among the scouting and technical team members.

There are risks in this approach especially if – as seems the case – it centres around trying to get to players before they hit stardom. At a smaller club this might be very much the finest option, at a bigger club there is always the pressure to go for the big name who can deliver immediate results.

“It is true that at a club like Liverpool you have more pressures than say at Norwich. That can be a problem because you don’t necessarily have the freedom to do what you think is best,” Kuper admits before continuing “then again, Liverpool have advantages over smaller clubs like Norwich in that they have more money. The main thing, however, is that you have to be brave. For a few weeks the fans might be angry if you sell a big-name player or happy if you buy a big name but in the long run what they’re really looking for is to win games. If you make moves that will ultimately lead to that result, then in the long run they will be happy.”

The most prominent example of this system remain Lyon, who managed to win seven consecutive league titles in France. Yet Lyon have since fallen on hard times. There are a number of theories about this decline but, according to Kuper, “they won the French league seven times in a row which is like say Southampton doing that in England. The thing is that they were the best in France, which they should have been happy with, but they had this dream of being champions of Europe. The thing is that in order to get the star players to do that Lyon had to pay too much money and got players who didn’t really deliver. In the end it was difficult for them to make the step up from being best in France to being among the best in Europe. Given the size of their club, they probably shouldn’t have tried.”

Lyon’s decline coincided with the rise of cash-rich clubs like Paris St. Germain. Which leads to the doubt that money will, ultimately, always win out irrespective of how intelligent other clubs tend to be.

“In the book we say that in the long run money is responsible for 90% of success. Yet you still get great managers who over-perform and achieve success even with shortfall in the budget. Manchester United is not only driven by money and Alex Ferguson has done a great job in keeping them successful. Arsenal as well. You can be successful without spending as much as the others but it is very difficult.”