It’s one thing Alex Ferguson misleading the press about the plight of Liverpool Football Club, quite another them lapping it up like suckling pups. Of course, not that you’d expect a lot more from the worst breed of hacks with their pre-set narrative.

Blaming Rafa Benítez for the financial implosion rather than the Reds’ hated owners is a low blow, even by his standards in verbal scraps with the Spaniard.

My new book – which looks in great detail at the correlation between spending and success in the Premier League era – heaps plenty of praise onto Ferguson, amongst others whom I wouldn’t invite to my fantasy dinner party. It heaps praise on him because, despite my known allegiances to Liverpool, the numbers from our research often speak for themselves.

While I obviously provide extended analysis, it is done with my neutral hat firmly donned, as was the case with my co-authors, Graeme Riley and Gary Fulcher. We respect the research, not personal preferences. On top of this, esteemed writers and bloggers associated with all 43 clubs to play in the top flight between 1992 and 2010 were invited to study the data and provide their insight for their club’s section of the book.

Crammed within “Pay As You Play” are many types of analysis, all based around the ‘true’ cost of teams and squads over the past 18 years. After all, this is a book based on the Transfer Price Index, which Graeme and I devised as a way of comparing on equal terms a transfer in 1993, for example, with one from 2007.

Spending £10m at a time when it’s not a lot of money is different to spending £10m in an era when it is. Equally, spending £10m in a depressed market, when transfer fees are generally lower and few clubs are splashing the cash, means it is more, in real terms, than £10m spent in an inflated market, when everyone else is paying similar figures.

Having first calculated ‘football inflation’ in the same way economists determine the Retail Price Index (except we used a ‘basket’ of every single footballer bought and sold each season, rather than grocery produce; although a few rotten eggs were still included), we could apply it to all manner of ideas and analyses far too numerous to detail here. Some of football’s most renowned thinkers (none of them Liverpool fans) have expressed their fascination with the project, so we feel we’re on the right track.

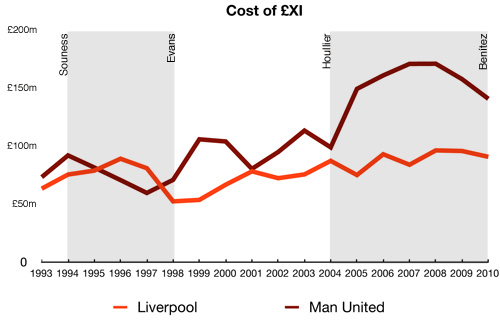

An absolutely key finding – the one that tallied most closely with league success or failure – was the average cost of a club’s XI (with inflation taken into account) over the course of a season: for the purposes of the book, called its ‘£XI’.

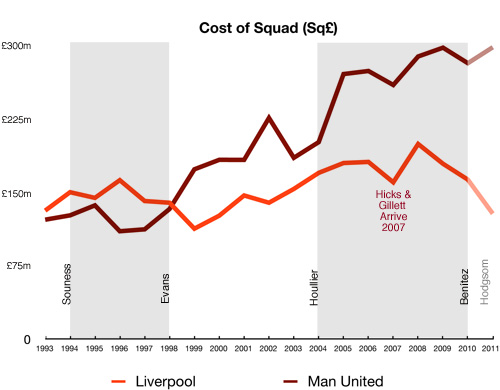

We did the same with squads (Sq£), and while that also plays a part, success or failure more often comes down to how much of a club’s purchased talent actually makes it onto the pitch throughout a campaign. (Either because money was badly spent on useless squad players, and/or because key signings were out injured.)

In essence, it is the financial weight a club punches that season; and success can be rated ‘pound for pound’.

And talking of weight, all managers had their figures presented first in their actual form, and then ‘weighted’ against the averages for the level of attainment they reached. We even managed to calculate the cost, in millions, of every point won, including the differences at various levels of the table. So it’s not the fashionable or most lauded managers who necessarily come out top.

Now of course, not every eventuality can be taken into account, and we are not saying that other factors do not play a role; clearly they do. But most of these are also discussed in full in the book, in a way that can’t be done here. Age, tactics, motivation, crazy chairmen: these are not ignored.

It’s fair to say that when managers buy players they often sell players at the same time. Gross spends are usually misleading, but even a net figure doesn’t explain the starting point; after all, Carlo Ancelotti hasn’t spent that much in comparison to Jose Mourinho because he inherited a side that was already a well-oiled machine, with a deep squad behind it, whereas managers have taken over at other clubs and been unable to see the deadwood for the dying trees.

Some of the measures in “Pay As You Play” show that, on plenty of occasions, Alex Ferguson’s success was earned rather than bought. Other parts of the study highlight the inspired work of people like Sam Allardyce and David Moyes at certain points during the past decade; real achievements in certain seasons given their budgets. As a Liverpool fan, I do not love these men. It’s not my life’s ambition to make them look good. But I’m happy to praise their work where praise is due, and to verify with fans of those clubs that the approach taken is fair.

However, none of our research shows Rafa Benítez to be anything approaching the root of Liverpool’s financial problems in the past few years, in the manner Ferguson suggests. Indeed, it shows a job well done by the Spaniard, based not on my bias but on the cold hard facts. Benítez does not come out top in any of the numerous categories, but he is consistently one of the better performers.

What the research does show – in crystal clear form – is that Liverpool were never more financially adrift of Manchester United in terms of £XI and Sq£ than during the past six years. Indeed, it clearly points to an expensive Liverpool team in the ‘90s performing well below expected levels, with the Reds growing increasingly poor in relation to other big clubs.

In current prices, the Liverpool squad of the past couple of years did not cost much more than that from the early to mid-‘90s; and yet all big clubs have had a greater number of players in their squads since the turn of the millennium. Relatively speaking, therefore, it is far less expensive in its assemblage.

Also, the ‘90s blessed the Reds with their best crop of youngsters (ditto United). And yet, despite these ‘free’ players, results remained below par. (Wages play a role too, and that is discussed in the book. However, we feel that, overall, the £XI is vital.)

Roy Evans invested badly in several instances, and didn’t sign any outstanding players; but he did get the team playing some highly watchable football, and got within the ballpark of the title. The problem, as I clearly outlined in “Dynasty”, was Souness. Although a different, more scientific form of analysis is used for “Pay As You Play”, the result is the same. It all comes back to Souness.

(It’s also true that Kenny Dalglish’s purchasing, post Hillsborough, was not up to his usual standards, and the squad was getting old. But that does not mean that Souness, when handed a fortune in today’s money, can be excused such awful use of it.)

On the whole, with just a young few gems (Fowler, McManaman and Rob Jones), Souness bequeathed Evans a collection of expensive misfits, and the club have not recovered since. When Jamie Carragher recently said that it was Souness and not Ferguson who knocked the Reds of their ‘fucking perch’, he could well have been quoting from “Dynasty”. This is now confirmed in “Pay As You Play”.

Liverpool entered the Premier League era with a more expensive squad than any other club. Bear that in mind at all times. That’s where the money went.

But recently, in real terms, the Reds have been cut well adrift of three über-squads (Chelsea, City and United), and even lag a long way behind Spurs.

Despite a less expensive squad, United, in winning the inaugural Premier League title, fielded the most expensive XI on average; their £XI was £10m more than that of the Reds, in current prices. This is perhaps because by that stage Ferguson knew what he was doing in the transfer market, and with his team in general, and Souness didn’t.

The cost of the £XIs of both clubs change positions over the coming years in terms of whose was more expensive, but 1997/98 is when a gap starts to emerge in United’s favour. Success in the Premier League and money from the Champions League led to increased investment by Ferguson in his team. By 2000, most of Liverpool’s serious money had been spent.

The £XIs converge again around 2001, with United’s falling and Liverpool’s rising until they almost meet. What’s interesting is that this is the time when the Reds start to resemble a really good side again (winning the treble), and in 2002, with the gap still narrow, even finish above United in the league.

But then United widen the gap in 2003, and win the title; Liverpool are now in decline, with Houllier having blown his transfer budget on a series of duds from the French league. In 2003/04 the clubs are again closely matched in terms of £XI, but neither team is performing as well as it has in the past couple of seasons, although United are a long way ahead of the Reds in league points.

However, a real chasm then emerges. United absolutely blow Liverpool out of the water in terms of £XI and, to a slightly less dramatic degree, Sq£.

The year? None other than 2004/05, Benítez’s first.

Let’s be clear: pound for pound, Liverpool’s performance in 2008/09 was fairly incredible; one of the four best posted by the 36 top two sides in the past 18 years. (United and Arsenal, twice, complete the quartet; more on this, and the over-performance of other clubs in the book.) But of course, it wasn’t enough.

It was the closest the Reds have got to United in the past eight years, and the closest to the eventual champions in the Premier League era. What’s interesting is that it was the closest to that point in time that the two teams had been in terms of £XI during Benítez’s reign. But the Reds’ £XI of £96m was still a long way behind United’s £158m. That season, pound for pound, Liverpool performed better; but United just had too many pounds (and, of course, prior experience; there’s more on what it costs to win a ‘first’ title in the book).

And in terms of overall squad costs (Sq£), it’s a similar story. Liverpool’s collection of players were more expensive up until 1999. Since then, 2003 and 2004 are the only two occasions when the two have been remotely close, with United well ahead the rest of the time. If Benítez had wasted so much money, where did it go? – because the squad was not getting any more expensive. Yes, money was spent, but less than what was being recouped.

And the bad news for Roy Hodgson is that the gap, which had narrowed slightly in 2008, is now widening again; United have invested more this summer than the Reds, who, on the whole, have lost more talent than they’ve gained.

There’s a lot more of the good and bad of both clubs in the book, along with the successes and failures of the other 41 clubs in the Premier League up to the end of 2009/10. At the very least, we hope that it provides some food for thought, no matter who you support.

“Pay As You Play: The True Price of Success in the Premier League Era” will be released in November, RRP £10.99.

Some of the unused Liverpool analysis will be made available to Subscribers of this website.

ISBN 978-0-9559253-3-7