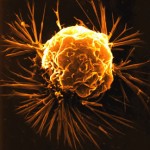

For me, complaining about the manager is like being concerned with a splinter while suffering from cancer. The cancer is what needs excising.

But the trouble with cancer is that not only does it spread, it affects the body as a whole. Even seemingly unrelated physical problems trace back to the underlying disease.

The problem for Benítez, as I see it, is that in light of the problems at the core of the club, there are no assurances that next season will be any less chaotic than this.

The problem for Benítez, as I see it, is that in light of the problems at the core of the club, there are no assurances that next season will be any less chaotic than this.

Whatever he has done wrong (and he’s made mistakes this season, as have the players, the referees, the hierarchy and even the fans), he has been juggling with one hand tied behind his back; no wonder balls have been dropped.

There are many reasons this campaign has been like a form of torture, and I will cover most of them. But this is about how the heart of the club is being squeezed and strangled from afar.

2008/09 Hangover

It seems that at the end of last season, the senior players and management felt that it had been a case of putting every last ounce of energy into the campaign, in order to overachieve but, demoralisingly, come close and yet still fall short. With the resources, that was the best they could physically do; and yet still cretins criticised them for ‘throwing away’ the league title, as if getting more than 86 points in any season is a doddle.

Indeed, with a small squad in terms of numbers (when compared with Chelsea and United, whose squad costs and wage bills have both remained much higher since 2004), the Reds had faced five years of constantly demanding football; the league form was excellent in alternate years and ‘decent’ the rest of the time, but crucially, cup campaigns – particularly in the Champions League – meant extra effort was required.

Add the fact that in this time the demands on Spain’s internationals increased, and it’s not too far-fetched to suggest that the Reds simply ‘hit the wall’.

Key players had been giving their all, season after season, to try and overcome the handicap of a relatively small squad in relation to what was expected. And perhaps the summer of 2009 was when that mental and physical exhaustion hit home.

The squad was also underfunded in 2008/09, but the players outperformed; the fear, a year later, was that they would be swamped by stellar expectations, while simultaneously understanding the need for three or four additions to the squad, on top of those being replaced like-for-like. But only the latter happened.

(Also, if you are replacing three excellent players like Alonso, Arbeloa and Hyypia, then the law of averages suggest that even the best judge of player probably has to buy five or six; after all, no-one gets close to a 100% success rate. And even if you get it spot-on, those players still have to adjust and adapt – they will not instantly play like those who were settled at the club for years. See Kyrgiakos – pretty shaky at the start, but fairly Hyypia-esque after Christmas.)

This time, a larger-than-expected injury crisis could not be overcome. A year earlier, Liverpool had Robbie Keane who, despite his failure to shine, at least offered an extra body and some experience to deal with Torres’ absence. Yet when Benítez went to reinvest that money in the summer, it had gone. Where? Debt repayment. And to make matters worse, it seems that it vanished midway through the summer, throwing the manager’s spending plans into disarray.

You can’t totally exempt anyone on the coaching or playing staff from their share of criticism (with the possible exception of the flawless Pepe Reina), but equally, a well-run club makes for a happy and supported manager, which in turn makes for happy and supported players.

Maybe Steven Gerrard wouldn’t have had such a poor season (by his standards) if an already undermanned squad wasn’t further undermined by cutbacks. (Some people blame Gerrard’s form on the sale of Alonso, over which he was reported to be ‘gutted’, but he was desperate for his best mate in football, Gareth Barry, to join the Reds. Alonso was also looking for a return to Spain, and it took both he and Benítez to fall out, not just one of them.)

As I’ve said before, Gerrard was overdue a bad season, and that doesn’t mean he should be shipped out (ditto Benítez).

Alas, it just happened to coincide with Carragher and Mascherano starting sluggishly (before recovering well), more injury woes for Torres, and a whole host of injury and form issues, mostly affecting the defence and the attack.

Aquilani’s extended injury problems meant he couldn’t contribute as expected, and with hindsight, another player might have been purchased instead. However, he was bought for the long-term, and I don’t think anyone saw the Reds being well out of contention by the time he was available and, of course, match-fit.

His injury record meant he came with a warning, so some of that responsibility has to be borne by the manager. But the employment of Mascherano and Lucas in the centre of the park meant that two attacking full-backs could be deployed; which, in terms of supposed negativity, is no different from deploying one steady, solid full-back and one attacking midfielder.

A poor pre-season, disrupted by the late return of the Spanish Confederations Cup players, carried over to the first three league games, and by then, it was a season of firefighting and plugging holes in a breaching dam.

And while Liverpool were awful away at Fiorentina, elimination from the Champions League effectively came at the hands of very late Lyon goals in both fixtures, neither of which were especially deserved.

Having ridden their luck at times in previous seasons, the Reds were experiencing every kind of setback imaginable. Fine margins were telling; for the second season running, the Reds would lead the league in striking the woodwork (which can mean not being accurate enough, but also mean coming mightily close), and experienced a decade’s-worth of bizarre refereeing decisions in one campaign. Not necessarily excuses, but certainly some extenuating circumstances.

Ultimately, though, it comes back to the strength of the squad. Rather than keep good squad players and simply purchase new first team players, Benítez has had to sell the former to finance the latter. I’ve made this point on many occasions, but this piece will go on to highlight just how it’s hit the club.

Finances For Failure

Since the arrival of Gillett and Hicks to England, the list below is the net spend of the top seven clubs. (At £27m, Liverpool’s 3-year spend is less than the £40m interest payment from the past year alone. The debts are crippling the club, clearly.)

Of course, a low net spend relies on having saleable assets to start with, and doesn’t take into account the different starting points for each club. But it gives an idea of what’s been coming in and what’s been going out.

1 Manchester City £262m

2 Tottenham Hotspur £76m

3 Aston Villa £64m

4 Manchester Utd £33m

5 Liverpool £27m

6 Chelsea £25m

7 Arsenal Profit +£22m

Now, the main factor is how strong this spending – nor lack of – left each squad in 2009/10.

Chelsea’s net spend is low in that time because they spent hundreds of millions – net – between 2003 and 2006, and still have most of those players. So it’s the cost of the squad as a whole that reflects financial wherewithal, along with the wages paid to them.

Chelsea and United have continuously had squads that cost over £200m, as well as the biggest wage bills in England (a large wage bill is necessary for a sizeable squad).

Liverpool’s squad cost (just £150m at the start of the season and £143m now) is getting lower all the time, and is well behind that of Spurs, let alone Chelsea, United and City.

And while the “value” of Liverpool’s squad might be far in excess of £150m, this value (as well as the wages paid to those like Torres, Reina and Gerrard, who are clearly worth more than they cost) is tied up almost exclusively in first-team players.

Therefore, injuries and/or a loss of form is far more hard-hitting.

This last point led me to examine the squads of the top seven in a new way.

First, there is obviously the cost of each squad; the natural starting point.

Including players who were at each club for at least half of the 2009/10 season, the following totals will be fairly (if not 100%*) accurate.

(*Getting 100% accurate transfer data is impossible, for various reasons I’ve explained in the past. But I make every effort to be as accurate as possible.)

1 Chelsea £235.8

2 Manchester United £217m

3 Manchester City £212m/£250m**

4 Spurs £195.6m

5 Liverpool £150m

6 Aston Villa 118.2m

7 Arsenal £95m

(**£250m if including those out on season-long loans, and who didn’t represent the club this season.)

But as people keep telling me, this doesn’t account for players like Steven Gerrard, who cost nothing, but are worth millions.

So I went through each and every squad player at these seven clubs, and awarded them a ‘value’ mark out of 10 in relation to what I thought their wages would be: after all, wages are the best indicator of a player’s value – transfer fees vary for numerous reasons, but wages are what the club tells the player that he is worth to them, and if they do not reflect his input, he looks to move on.

For example, someone like Gerrard, who didn’t cost a penny in terms of a transfer, is clearly a ’10’ when it comes to weekly pay packet.

Other 10s are people like John Terry, Michael Ballack, Carlos Tevez and Wayne Rooney: basically, anyone on more than £100,000 a week. Some clubs have a more rigid wage structure than others, and only certain individual salaries are well-known, but it’s possible to get an idea.

Now, this is based mostly on estimates, so bear with me; I’m not claiming that this is scientific, but it does involve educated guesses. And vitally, for terms of accuracy, the overall squad ‘values’ tally with known rank of wage bills, which is as follows:

1 Chelsea

2 Man United

3 Man City***

4 Arsenal

5 Liverpool

6 Spurs

7 Villa

(***estimated, now that they have at least six players on £100,000 a week)

Therefore, the average squad value/wage will reflect the positions shown above – although expanding squad sizes at City and Spurs will have radically increased their wage bills since the last annual reports. (And, of course, Spurs’ will rise significantly now that players will seek remuneration for their efforts

If someone costs a fairly hefty £15m, they might not necessarily be on a ’10’ wage, but it’s highly unlikely they’ll be much below 8; their fee tells us that they were in demand. Similarly, anyone who gets close to the British transfer record has to be earning a 9 or a 10.

Alternatively, if a cheap or free player has been at a club for a number of years, and awarded new contracts, chances are his wages will also reflect a growing importance; after all, if you don’t reward his progress, he’ll run down his contract and leave for free.

Findings

What I found was that there is not a whole lot of difference between the ‘value’ of each club’s First XI. Chelsea, United and City comprise the top three, as you’d expect.

Arsenal, who on average don’t pay a lot in transfer fees but who are known to have a reasonably high wage bill, see this reflected in how their XI scores a higher average than Spurs or Villa.

Liverpool’s XI also scored higher than Spurs and Villa, and around the same as Arsenal’s. (Which is reflected over a the past few seasons, when there’s not been much to choose between the two clubs.)

But the real difference was in the ‘value’ of squad members. By my valuations, Liverpool experienced the biggest drop, thanks to players like Ngog, Insua, Degen, El Zhar and Kyrgiakos, none of whom will be pocketing large salaries.

And indeed, Spurs provided the main surprise, with their squad players possessing more value than their First XI!

(This is because I anticipate that players like Dawson, Assou-Ekotto, Huddlestone and Lennon are not on stellar wages; however, this might change when their contracts are renewed. And unlike other clubs, the inclusion of players like Bentley, Pavlyuchenko, Hutton, Woodgate, Jenas, Bale, Bassong and Keane means that as well as fairly hefty wages for players not getting regular starts, they also had a very expensive bench; the squad players costing more than this season’s main men.)

‘Value’ of back-up players in relation to First XI

1 Spurs 129%

2 Man City 93%

3 Chelsea 90%

4 Man United 87%

5 Arsenal 82%

6 Aston Villa 82%

7 Liverpool 79%

In other words, out of the top seven, Liverpool had the lowest valued non-first XI players when compared with those in the ideal team.

The average value/wage rank (out of 10) for non-XI players was as follows:

1 Chelsea 7.7

2 Man City 7.3

3 Spurs 7.1

4 Man United 6.5

5 Arsenal 6.4

5 Aston Villa 6.4

7 Liverpool 5.6

Remember, this is purely my attempt at valuing the players. But it does suggest that in building a side that can compete for the title (as seen last year – there’s no doubt that the majority of first XI players are of top-class pedigree), Benítez has had to sacrifice squad depth.

Also, of the £150m spent on players who featured for Liverpool in 2009/10, £104m was wrapped up in the ‘best XI’.

Indeed, the best XIs of Chelsea, Man United and Man City all cost in excess of what the ENTIRE Liverpool squad that ended the season cost to assemble.

The alternative?

Given that the squad has rarely cost over £150m in Benítez’s time, and that the current season ends with it closer to £140m, the alternative approach would have been to spread the expenditure; so no Torres, Mascherano and Johnson (or Alonso, when £10.5m was a fairly big fee; £20m in today’s money according to TPI), and no Keane and Aquilani.

Instead, a greater number of players, hopefully like Agger, Reina, Kuyt, Crouch, Garcia, Skrtel and Benayoun.

Of course, this almost inevitably means fewer world-class players; while not impossible, it’s far more difficult to find them in the middle-to-lower tier of purchase prices. Such an approach wouldn’t have won the title, or even got close in the way it did last year, but it might have cemented a top four place.

This season, it ‘might’ have been better to have 24 ‘very good’ players, rather than a few injured/out of form world-class ones supplemented by some cheap gambles. But that’s this season; next season could see different levels of fortune with injuries.

One More Alternative

There is one further alternative: the Arsenal route; i.e. grow your own. But to do this you need a) excellent scouts, and b) excellent Academy staff to train, guide and develop them. It’s debatable that Liverpool have had either of these in recent years; certainly not to the level required in the modern, multi-cultural game.

Last year, Rafa Benítez brought Rodolfo Borrell to the club – the man responsible for much of Barcelona’s incredible success. He was not impressed with what he found upon taking over from the staff employed by Rick Parry in 2007, and outdated ideas going back well beyond then. The scouting set-up was also an amateurish mess.

Since then, the U18s have been revamped, with new additions to the squad. The initial signs are very promising, but it could take years for it to bear fruit. That’s the problem with youth development – it takes a hell of a lot of time, and requires masses of patience.

And rather than rely on almost 100 part-time, amateur local scouts, some of whom were in their 80s, Benítez has whittled it down to a dozen-or-so professionals.

But it is areas such as this, and in appointing one of the world’s leading sports scientists, that Benítez is working to improve the club in fundamental, long-term ways.

Alas, too few people realise this.

The Power to Act

Good managers have been here before: having to act after a bad season.

They are then backed to act swiftly and decisively; rid the camp of the deadwood and the disruptive. Bill Shankly, another who distrusted the powers that be (and threatened to walk out time and again) had a similar period circa 1970, and he was able to act with power and ruthlessness, even though his last trophy was four years earlier (and his next would take a further three years).

But what can Benítez do? Buy players? – with what money?

And who of any merit would join the club in such uncertain times?

Indeed, one way of rescuing a season is to spend big in the winter transfer window; never ideal, but it’s been known to work. Again, Liverpool lost more players (Voronin and Dossena) than they gained (free transfer Maxi).

Until the club is sold, no-one can plan for the future. With the season ending this weekend, now is the time to be making moves in the market. Instead, everyone finds themselves in a debilitating limbo, while the World Cup could very well inflate the prices of any potential targets.

And even if a buyer for Liverpool is found in 2010, will it be in time for next season? (Not just the deal wrapped up in time, but being able to recruit new players.)

And if you were a manager under fire, would you hold out in the hope that the next lot of promises aren’t broken too?

Let’s face it: Liverpool FC needs chemotherapy – to nuke the malignant tumours at its core – but is more likely to get a sticking plaster.

Subscribers may discuss the article in question with me in the comments section below.

[ttt-subscribe-article]