Abridged excerpt from “Dynasty: 50 Years of Shankly’s Liverpool”, book available here.

Graeme Souness 1991-1994

Introduction

On paper it was the perfect appointment. A canny ex-Liverpool player (and a Scot, to boot) with exacting standards, and whose football education after leaving Anfield had continued in the rarified tactical arena of Italy, before enjoying success north of the border with Rangers — an experience through which, unlike the man he replaced in the Anfield hot seat, he gained several years of management know-how before taking the job. Four titles in five years at Rangers, where he ended an almost-unthinkable nine-year wait for the championship at Scotland’s most successful club at the time, suggested that Souness had everything needed to pump life back into a side that had started to show the first signs of deterioration. How could it go wrong?

Unfortunately, it did just that. Rather than end a long wait for the title, as he had at Rangers, Souness’ failure on a number of levels led to the start of an even longer period without a league title.

The Liverpool Graeme Souness returned to was clearly different from the one he had left seven years earlier. He inherited an ageing side heading for decline, but rather than arrest it, he hastened the fall from the summit like a mountain climber discarding his guide ropes in favour of overcooked spaghetti. He also clearly suffered some bad luck –– a serious Achilles tendon injury sustained while representing England rid John Barnes, the best player at the club, of his pace, and he was a shadow of his former self in between 1991 and 1994, while the massively influential Alan Hansen had just retired. But Souness’ failure in the transfer market, and his decision to insensitively sell a story to The Sun newspaper on the anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster, meant that he contributed to his own inevitable downfall.

The timing of Liverpool’s partial demise could not have been worse. The new financial landscape of the Premiership opened up in 1992, when the First Division changed its name. Meanwhile, the Champions League — in which Liverpool would not compete for almost a decade — was another cash-cow that began in 1992, when the European Cup was rebranded and the structure slightly altered, introducing a group stage and allowing more than one team from each country to participate. While Manchester United won league titles and cashed in on their success with heavy merchandising, Liverpool were left standing.

Also, Souness himself was going through changes. In 1992 he underwent a triple heart by-pass, something that would lead to him questioning his own inner strength, as well as indirectly leading to an alienation of many of the fans in its aftermath.

Situation Inherited

There can be no doubt that Graeme Souness inherited an ageing side about to head rapidly over the hill. Alan Hansen retired at the same time as Kenny Dalglish quit; the ultra-composed centre-back’s knees were already held together with sellotape and blu-tack. Ronnie Whelan turned 30 at the start of Souness’ first full season, as did Steve McMahon, while Ian Rush reached that age six months into his reign, just a couple of months before Steve Nicol and then Ray Houghton also entered their fourth decade. Plenty were already in their 30s: Bruce Grobbelaar was 33 –– a good age for a goalkeeper, but at a custodian’s peak, so he wasn’t going to get any better; Glenn Hysen was almost 32; David Speedie 31; Gary Gillespie was on the cusp of 31; and Peter Beardsley had recently turned 30. Ronny Rosenthal was almost 28, but his problem was more to with a lack of real top-level quality rather than age. Jan Molby was also about to turn 28, but lifestyle issues were clearly hindering the Dane from reaching peak fitness; at times he resembled a man experiencing a mid-life crisis.

Sprightly young footballers of sufficient quality were thin on the ground in 1991. There was Steve McManaman, with a handful of appearances to his name. The same applied to Mike Marsh and Nicky Tanner, although the latter — a chunky stopper — was never sprightly and hardly the sufficient quality either. Steve Harkness, Don Hutchison and Jamie Redknapp, signed by Dalglish, were all yet to make their debuts, but would feature in the first team within a year. Robbie Fowler was in the pipeline, but still two years away. Dominic Matteo was another who would come through the ranks in 1993.

One player who did have a lot of potential and time on his side was 22-year-old Steve Staunton, a versatile defender. Souness promptly sold him. He later admitted it was his one regret with regard to those shown the door, but explained that it was down to the ruling that limited sides in European competition to three foreigners, and an Irish lad was classed as just that. Staunton had some fine years at Aston Villa, but later returned to Liverpool when his best days were behind him.

The task Souness faced clearly involved culling some of the older players. But the problem was more about which players he sold, and those he chose to keep. He was right to retain Rush, who was lean and fit, as ever; despite being dropped by his former team-mate in 1992/93, Rush responded with the goals that dragged Liverpool out of the bottom half of the table, and he was still having a positive impact on the team in 1994/95, under Roy Evans. McMahon was possibly rightly moved on, seeing as he appeared to be a fading force and £900,000 was too good a fee to turn down. Speedie and Hysen were surplus to requirements, while Gillespie was 31, and as with McMahon, an offer of almost a million pounds was too good to refuse. And by purchasing David James in 1992, Souness was building for the future, something Grobbelaar did not represent.

But then it starts to get more confusing. In Souness’ first full season, Ray Houghton had been excellent, making his way into the six-man shortlist for PFA Player of the Year. Souness promptly sold him. Houghton did well at Aston Villa, proving his time was not yet up. Even more baffling –– the manager’s dunder-stroke –– was to sell Peter Beardsley … and not only that, to sell him to Everton. It’s always easy to say what might have been, but Beardsley and Rush could have continued their natural partnership for a few years to come; it wasn’t where the problems lay. A teetotaller, Beardsley fastidiously looked after himself, and was still going strong in the Premiership six years later. He managed another 210 top division matches for Everton and Newcastle United, scoring a further 71 league goals after his Anfield exit; not to mention countless assists. Souness later claimed that Beardsley and McMahon were looking for guarantees of first-team football and improved deals, without which they hinted they would leave. While he felt these and other older players needed replacing, he admitted he should have waited a year, in order to source suitable replacements first. He said he acted impetuously, and that it was a major mistake.

It wasn’t just the fact that Souness got rid of too many good players with plenty still to offer –– Houghton, Staunton and Beardsley in particular –– but it was that he bought far too many inferior players to replace them. The non-native European ruling meant that clubs needed to field home-grown players and limit overseas stars, but then how did Istvan Kozma fit in with this scenario when Beardsley didn’t?

Players Inherited

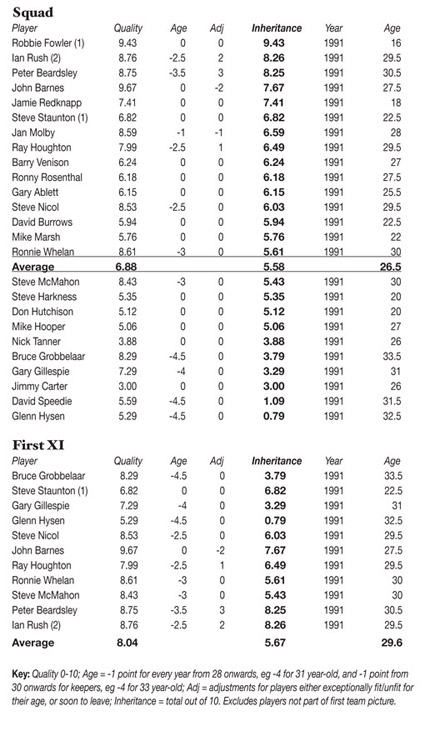

Souness claimed that “there were not many great players” at the club in 1991. In fact, he said there was just one –– John Barnes. In terms of Quality ratings [the average mark out of 10 given by the Brains Trust, see here for more info], he was right — Barnes was the only player rated in the ‘9’ category, but that was before taking into account the injury that almost instantly reduced his effectiveness by a couple of points. Souness admitted that Barnes was not the player he had hoped to find. Ian Rush was of course a truly great player over the course of his Liverpool career, but was proving less prolific in his second spell. While his all-round play had improved, he was not the world-class predator seen in his first stay. There were a lot of players rated between 8 and 9 in terms of Quality, but every single one was entering the final phase of his career, leaving a poor Inheritance value.

In terms of Quality, the Brains Trust rated the squad Dalglish bequeathed at a respectable average of 6.76. However, taking age into account, the squad rating drops to a very worrying 5.41 per player. The first XI has a Quality rating of 8.01 — which looks incredibly strong, and reflects the fact that the team were recent champions and challenging again in 1991 — but when the crucial age weighting is factored in, the Inheritance drops to an alarming 5.64. This was a team living on borrowed time.

The average age of the squad was 27, but more alarmingly, the average age of the strongest XI was 30. The imbalance in the squad can be seen by the fact that there were four young left-backs in Staunton, Burrows, Ablett and Harkness, but of course only one could play at a time; in central midfield and up front, however, all were approaching or already well into their 30s.

— State of Club (See book)

– Assistance/Backroom Staff (See book)

Management Style

Authoritarian, dictatorial, and ruthless: words that have been used to describe Souness. In many ways he has mellowed since he took charge at Liverpool at the age of 38, but back then he was by his own admission arrogant and abrasive, and in too much of a hurry. He felt “the job was easy” when he pitched up, but before too long realised it was quite the opposite.

Rumours about squabbles in the dressing room between the players and Souness were rife, with Ian Rush famously telling a Sky Sports interviewer that “teacups being thrown” was nothing new. Jan Molby saw both sides of Souness. “Unlike some of the players, I didn’t have a major problem with Souness,” he said in his autobiography. “Some of the lads didn’t like his managerial style, and it’s true he had a very short fuse. He’d come in after games and have a real pop at us. He was one of those managers who wanted to win so badly. Like Kenny, he was pretty calm before games, but afterwards he just couldn’t control it. In September 1993, we lost 3-2 to Wimbledon at Anfield in the Premiership. We really were pathetic. Souness was livid. After storming into the dressing room, he picked up a bottle of smelling salts and threw it at the mirror. It smashed into a thousand pieces. That was the worst I ever saw him after a game. He’d have a dig after most matches and then he’d go and sit down. But on a Monday morning, he was big enough to forget about what had happened.”

Many of the senior players were not prepared for the hard line taken by the new boss, with the situation perhaps exacerbated by the fact that several — Rush, Nicol, Grobbelaar, Gillespie and Whelan — had once been teammates. This was different to Kenny Dalglish taking control directly from within, not least because of the different personalities involved.

Souness felt the senior players lacked passion, and were becoming increasingly concerned with money; certainly they didn’t seem to share his overwhelming desire to win. Mark Wright and Dean Saunders had arrived on higher wages than experienced stars like Rush and Houghton, and the existing stars wanted to know why. “The Liverpool I left,” explained Souness, “was all about the dressing room and how good this team of professionals were. When I went back there I found a dressing room of people who were only interested in what their next contract was about and how much they were going to earn.”

But perhaps hypocritically, Souness had left Liverpool purely for the financial gain. “I am moving for the money. There is no use lying about it,” he said at the time. Later, in his autobiography, he said that he never wanted to leave Liverpool — his wife needed to get out of the country for tax reasons; but then how different is that to the players he inherited having their own monetary concerns or desires?

Rush, in particular, had a rocky relationship with Souness, and would end up being dropped in the second half of the 1992/93 season; whether or not it was intended to have such an effect, it certainly fired up the legendary striker, who returned to the team to score the goals that led the Reds away from a dangerous flirtation with the relegation zone.

Consolation at this time could be taken from the fact that Souness had fully blooded several new prodigious young talents like Steve McManaman and Robbie Fowler, allowing them to play and develop in the first team, where they were desperate to be — as opposed to many of the other senior players, according to Souness. He had also wanted the senior players to lead the way and set the example to the younger pros, in the way he had been shown the ropes by Steve Heighway, Phil Neal and Ray Clemence, and how, a few years later, he, along with Kenny Dalglish, had passed on his experience to the younger lads. But now — and this is something backed up by Roy Evans — most of the senior players seemed more concerned with themselves. A sense of selfishness and complacency had started to evolve. In the ‘70s and early ‘80s, the tendency for players to let their hair down with a drink was balanced out by the senior pros having a strong sense of knowing when the time was right, and they were also prepared to put in that extra effort in training to compensate. But now there was less responsibility being taken by the players.

However, for all his disagreements with Rush, Souness later praised the striker’s work with Robbie Fowler. Even before Fowler was in the first team, Rush was advising him in the finer arts of leading the line. While Rush wasn’t receptive to a lot of Souness’ ideas, at least he pleased the manager by taking an interest in the development of the next generation of stars.

Unique Methods

Graeme Souness tried to instigate change, and do what Alex Ferguson had done at United — namely remove complacency, stop excessive drinking, and rebuild an entire squad.

Making the break from the past seemed to be Souness’ main aim. Tommy Smith was now writing for the Echo, but also hanging around in the Boot Room. Souness felt it wasn’t right to allow a member of the press special access to the inner workings of the club, even if he was an ex-captain. Souness’ explanation was that his players, who were being criticised by the ‘Anfield Iron’ in his column, would think that he condoned Smith’s comments; as such, Smith was asked to stay away. The expulsion only served to make Smith a harsher critic: “He sees himself as a Messiah. But he is leading the club down the drain,” he said of Souness. Smith probably felt his presence was harmless, but clearly Souness had a point.

Jan Molby explained some of the changes taking place from 1991: “Souness seemed determined to shake things up on the training ground. He wanted Liverpool to be run along the lines of Sampdoria, whom he’d joined in 1984, but found it hard to get his ideas across. The famous five-a-sides were left intact but we first noticed the difference in his initial pre-season in charge. We had been used to doing everything short and sharp at Liverpool, with runs taking a maximum of eight minutes. Under Souness, they suddenly lasted 45 minutes!”

Molby claimed that Ronnie Moran and Roy Evans were upset by the changes, particularly to the pre-season training routine, which had been in place since the days of Shankly. But there was also the problem that the new methods were not working. “We ended up with more injuries — most of them to the Achilles tendon — in the first three months of Souness’s first full season than we’d ever had,” Molby explained.

Another problem area was the change to the daily training routine. Ever since Shankly’s desire to have the players feeling more familiar with Anfield, and also to enable a cooling down period after training, the players would meet at the stadium to get changed and then take a coach to Melwood, and everyone would return to the ground to eat lunch after the morning’s session. Souness felt that it made sense to have everything in one place — as is the case today. Anfield was becoming busier, with a shop open, function rooms hired out and a museum planned, and it was no longer as practical to get the players in and out.

Ronnie Moran, in particular, was resistant to change. He was old-school, and understandably not keen on altering the methods that had brought so much success. For his part, Souness, while respecting Moran, regretted that he didn’t push the issue harder with the coach; he didn’t want to completely move away from the ‘Liverpool way’, but felt certain changes were important. History would prove that it needed an entire shift away from Boot Room personnel to move the club into the modern age. In 1998, Ronnie Moran retired, and shortly afterwards, Roy Evans resigned. That allowed Gérard Houllier to make the essential changes to diet and preparation. Where Souness had felt constrained by those around him, Houllier was given carte blanche to alter things as he saw fit. While Houllier ultimately failed for other reasons — poor purchasing later in his tenure and limited tactics — the increased professionalism would prove to be beneficial in Liverpool’s resurgence as a successful cup team.

Souness was also blamed when the club knocked down the fabled Boot Room. The decision was made in order to expand the press room. Souness maintained that it was the club’s decision, and it’s easy to sympathise with his explanation that such moves “did not come within a manager’s brief”. But by that stage, he was being blamed for everything that was changing at Liverpool. As well as press and fan criticism, he was becoming increasingly unpopular with those inside the club. Looking back on his final days at Anfield, Souness said: “I daren’t play in a five-a-side, because if I collapsed, no-one would give me the kiss of life.”

Strengths

Souness was passionate, but probably to a fault. “No-one ever tried harder at Liverpool than Graeme,” Roy Evans later admitted. “I’ve never seen anyone so distraught when we lost games as he was. Sometimes you would fear for him getting into his car after a game, he looked so bad. I think, and Graeme would acknowledge this now, that he was too impetuous, wanting to change too much too soon. He discarded too many of the more mature players far too early.”

After his triple-bypass heart surgery, Souness wondered if he was made of the same stuff; instead of tough teak, he felt more like brittle balsa. After one defeat, against Ron Aktinson’s Aston Villa — a game famous for Dean Saunders, recently sold to Villa, scoring twice and Ronny Rosenthal, unbelievably, hitting the bar from a central position having gone around the keeper — Souness admitted crying all the way home in the car, having been due to join Atkinson for a meal after the game. He felt on the edge of a nervous breakdown.

Souness was a hard taskmaster, but tried to let bygones be bygones; however, once players were upset it was hard to turn them around. Having fallen out with Ian Rush on a number of occasions, Souness still made the marksman club captain. For a man seen as stubborn he could admit his mistakes, as Jan Molby attested. In 1991 he had told Molby that he didn’t feature in his plans, but was big enough to admit he’d made a mistake, and recalled the Dane to the team.

Having played in Italy, Souness was looking to bring a more continental approach to Anfield. In that sense it can be argued that he was ahead of his time. Rightly, he felt that the days of the team being handed fish and chips on the team bus after the game needed to be consigned to the past, and a move to a more athletically-propitious diet of pasta was implemented. Ian Rush, for one, didn’t take kindly to being told he couldn’t eat a steak three hours before a game; his argument was that it had served him well enough over the years. Souness’ counter-argument may well have been that Rush would be even sharper on a diet more conducive to aerobic exercise — something rival teams were no doubt cottoning on to, which would have given opponents more running power. And Rush wasn’t exactly scoring as he had been in the past, although his own Italian experience — shorter and less pleasant than Souness’ — perhaps scarred him to continental methodology.

Souness was a disciplinarian, but it is hard for one man to take on an entire squad which has an entrenched mindset, as Roy Evans later discovered. There may be some receptive players, but if they are in the minority, it’s a tough task. Ultimately, the best way to instil discipline is to change the personnel, although that’s easier said than done. If a manager can root out the hardcore of those who cause problems or resist instruction and — the crucial part — buy players who already have the right temperament, to lead by example, then he can have the team follow his thinking. But both Souness and Evans exacerbated their problems by spending a lot of money on players with questionable characters.

– Weaknesses (see book)

Historical Context — Strength of Rivals and League

When Souness took charge in April 1991, Arsenal were looking like becoming the dominant team. With the Reds having fallen away after the shock of Dalglish’s departure, the Gunners were on their way to completing their second title success in three years. But Arsenal’s time as a league force under George Graham had come to an end; they would win both domestic cups in 1993, and the Cup-Winners’ Cup in 1994, but they never again hit the heights under the Scot in what had now become the Premiership.

Leeds then briefly emerged as a real threat under Howard Wilkinson. Boasting an impressive midfield — Gary Speed, David Batty, Gary McAllister and Gordon Strachan — they won the title in 1992, helped partly by the introduction of Eric Cantona in the second half of the season. But Leeds finished 17th a year later, and their bubble had burst.

It was in 1992 that Manchester United finally appeared to be getting their act together as a league force, after cup successes in the previous two seasons. They pushed Leeds hard to the title, but lost 2-0 at Anfield in a game in which Ian Rush finally scored against the great rivals.

By the time Souness resigned, his friend and predecessor in the Anfield hotseat had not only taken Blackburn into the Premiership but had them on course to finish second in 1994, a year before landing the title. Like Souness, Dalglish had spent big, but unlike Souness, he got his key signings spot-on. There was clearly less pressure at Blackburn, and Dalglish no doubt had a freer hand to do as he wished — as opposed to what Souness was finding at Liverpool. But whereas Souness showed an interest in Leeds’ David Batty, Dalglish went out and got him. Whereas Souness looked at Tim Flowers, Dalglish signed him. And within a year of Souness breaking the bank to sign Dean Saunders, Dalglish had snapped up Alan Shearer.

– Bête Noire (See book)

– Pedigree/Previous Experience (See book)

– Subsequent Career (See book)

Defining Moment

Clearly the defining moment of Souness’ Liverpool stewardship was the heart bypass surgery which took place at the time of the FA Cup semi-final against Portsmouth in April 1992, and how he promptly sold his story to The Sun; as far as fans on Merseyside were concerned, it might as well have been his soul. It was bad enough that he sold an interview and pictures of himself kissing his girlfriend upon the operation’s success to that particular newspaper — which is still reviled for its dishonest and deeply insulting reporting of the Hillsborough disaster, and remains boycotted on Merseyside –– but to do so on the eve of the third anniversary of the tragedy was unfathomably crass. To make matters worse, the piece, which was due to appear on the 14th, ran a day later, on the 15th –– the very anniversary of the loss of 96 lives. Although he apologised profusely at the time, Souness later admitted that he probably should have resigned. Any goodwill left from his playing days which had survived a turbulent first season in the league was wiped away by needless and selfish actions. It could be argued that he wasn’t thinking straight, but it seems that he knew what he was doing.

For Souness himself, the defining moment in terms of knowing he had reached a dead end came on the afternoon of the FA Cup 3rd-round replay defeat by Bristol City in January 1994. City were staying in the same hotel that Liverpool used ahead of preparations for an Anfield game, and were in the suite next to Souness’ room for a pre-match briefing. Russell Osman, the manager of the opposition, was giving his team talk, and Souness could hear every word. Every individual’s weaknesses were correctly assessed. The damning statement that if you matched Liverpool for effort then the Reds would crumble was something that, painfully, the Liverpool manager knew was only too true. City did just that, and won 1-0.

– Crowning Glory (See book)

– Legacy (See book)

Transfers In

All managers forage in the market they know best, but Graeme Souness had a strange habit of not only plundering leagues in which he’d managed, but also recruiting players who had previously played under him –– and not always the best ones at that. For instance, when he later managed in Turkey and Portugal, and back in the Premiership with Blackburn, he bought ex-Reds Mike Marsh, Barry Venison, Stig Inge Bjornebye, Brad Friedel, Michael Thomas and Dean Saunders. Players he sold at Liverpool, like Marsh, Saunders and Venison, he ended up repurchasing when they were past their peak, although he did get the best from Friedel at Blackburn, who was originally brought to Liverpool by Roy Evans.

Whatever the reason for the failure of many of Souness’ signings –– and many did fail –– it’s fair to say that at the time they were purchased, quite a few made reasonable sense. He would regularly spend big money on established players who had done well in the old First Division/newly-formed Premiership. Perhaps these players just couldn’t handle the step up to the biggest club in the land, or maybe Souness’ management skills were woefully lacking. It’s possible that some were simply not suited to the Reds’ style of play; and then there’s the likelihood that they were simply good top division players, but rarely great ones. Where was the real outstanding talent?

It seems there is evidence of a deficiency in Souness’ scouting system throughout his career after leaving Rangers. Of course, there’s the infamous story of Ali Dia, widely believed to be the worst Premiership player in its history when he briefly appeared for Souness’ Southampton in 1996 — which seems to sum up the Scot’s attitude to recruitment. Phoned by someone claiming to be former World Footballer of the Year George Weah, Souness was offered the African’s cousin: Ali Dia, a Senegalese international who had previously played for Paris St Germain’s first team. Of course, it was not Weah, and Dia was not Weah’s cousin. Nor was he an international or a former Ligue Une player; he was little more than a parks player. With no chance to see him in a reserve fixture, Souness brought on Dia early in a Premiership match against Leeds United. So bad was he, Dia was himself removed on 53 minutes. Dia’s one-month contract was promptly cancelled. Can you imagine many other top-level managers making such a bizarre mistake? (Souness has since criticised some of Rafa Benítez’s signings, including Yossi Benayoun, saying he was ‘not Liverpool standard’. How dare he? some might ask. Mischievous souls might suggest that some of Souness’ signings at Liverpool made Dia look like World Footballer of the Year.)

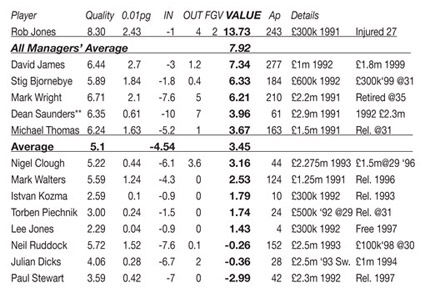

At the start at Liverpool, Souness went in big and hard into the transfer market, just as he always had with tackles. In July 1991 the Scot paid £2.2m for Mark Wright, in what seemed an inspired move. Wright had excelled a year earlier at Italia ‘90 as England came within a penalty shootout of the World Cup Final. However, and perhaps crucially, it was as a sweeper, playing behind two stoppers that he excelled. Maybe this would be why Wright never found his best form under Souness in a 4-4-2, and only rediscovered his class in the mid-’90s, when Roy Evans adopted a formation with three centre-backs. In 1998, aged 35, Wright retired after 210 games for the Reds, having scored nine goals.

At the same time as he moved for Wright, Souness raided relegated Derby once again, this time for Welsh striker Dean Saunders, son of former Red, Roy. The English transfer record was broken in the process, as Liverpool shelled out £2.9m to partner the striker with his fellow Welsh forward, Ian Rush –– the club’s previous record signing. Saunders was a capable, busy striker, who could score goals without ever being particularly prolific. He scored 23 goals in his first season, but nine came in the UEFA Cup, against very substandard opposition, and four more followed in the domestic cups; meaning that only ten came in the league. Too often his control seemed lacking, and he couldn’t utilise his pace on the break in a side that played possession football. Two more goals would be scored at the start of the following campaign before, in September 1992, Saunders was sold. As with later record-breaking signing Stan Collymore, Aston Villa came in and took the player off the club’s hands, for about 85% the original fee, but by which time the transfer ceiling had risen. A couple of months after Souness signed Saunders, Ian Wright moved to Arsenal for £400,000 less; the Londoner may or may not have done as well at Liverpool, but he proved to be a far more effective Premiership goalscorer over the coming years.

Mark Walters arrived for £1.25m in August 1991, having scored a goal every 2.7 games at Rangers, but during his Liverpool career that ratio was a far less impressive one every 6.5 games, although quite a few of those appearances were as substitute. Walters was a fine player, but was always going to suffer by comparison with the recent memories of John Barnes at his best. Walters scored 19 goals in 124 games, but aside from 1992/93, when he scored 13 in 44, his contribution was too often lacking. He was released in 1996.

Michael Thomas looked like another shrewd signing, when he arrived in December 1991 for £1.5m. A box-to-box midfielder, the former Arsenal man, whose fame was cemented at Anfield two years earlier, would offer the kind of running his new midfield partner, Jan Molby, could only dream about. But as with John Barnes, Thomas suffered a debilitating Achilles tendon injury during the Souness reign, and emerged at the other side a diminished force. He would later establish himself in the Reds’ midfield under Roy Evans, but as a holding midfielder whose job was to break up attacks and give simple passes. While not an outright failure, he did not live up to the expectations that came with a transfer fee that, by 2008 standards, would be the equivalent of around £15m. After 12 goals in 163 games, Thomas moved to Benfica.

Another midfielder arrived a few months after Thomas: Istvan Kozma, signed from Scottish football in February 1992. In the March of that year, 18-year-old Lee Jones was plucked from Wrexham for £300,000. Jones would later go on to prove a handy lower league player, but during his five years at Anfield he only made four appearances, all as a substitute.

The summer of 1992 showed no let-up in the rebuilding programme. David James arrived for £1m from Watford, for whom the 21-year-old had played almost 100 games. James was hugely talented, with the perfect physical attributes to be the very best. But the psychological side of the game would always hamper him –– decision making, confidence and concentration. Capable of pulling off breathtaking instinctive saves, he fared worse when he had more time to think. It seemed that boredom crept in during games –– he had to be involved, and would come for crosses when there was no need; although at least the defenders knew they had a proactive goalkeeper behind them, and not some timid soul rooted to his line. He also admitted spending too much time playing his Playstation, and not preparing properly for matches. Part of the problem was that he was still very young for a goalkeeper, and once he had made costly mistakes at such a high-profile club, he was mentally scarred. The cutting headlines –– “Calamity James” –– must have hit him hard. After 277 games, he was sold in 1999 to Aston Villa, for £1.8m.

When he was signed from Spurs in July, Paul Stewart, approaching his 28th birthday, had just made the PFA shortlist for Player of the Year. He had also recently won three caps for England; as such, it seemed that he was a player on the up. Souness paid £2.3m for the former striker who was now making his name as a holding midfielder. But Stewart never settled at Liverpool, where expectations were higher, and where he was expected to seamlessly transfer his midfield form from Spurs which, in itself, had come about after three years of failure as a forward. Injuries didn’t help his stay on Merseyside; as a result, he seemed slower and more cumbersome without full fitness. In a midfield that could contain a now-overweight John Barnes and the considerable frame of Jan Molby, Liverpool were about as far from athletic as you could get. Julian Dicks and Neil Ruddock would soon add more weight to the back line, albeit in the wrong sense, while Ronnie Whelan was nowhere near as trim as in his youth. Within four years Stewart would leave on a free transfer, to cap another bad foray into the transfer market by Souness.

Rather than get better, Souness’ signings only seemed to fare worse. Torben Piechnik was signed for £500,000 in September 1992. Piechnik was far from poor in terms of pedigree; he had only just helped Denmark, who hadn’t originally even qualified for Euro ‘92 (but were allowed entry due to Yugoslavia’s civil war), win the competition in one of the biggest upsets of all time. Part of their success was attributed to a lack of pressure; they weren’t meant to be there, so they had nothing to lose. The same could never be said of a player joining Liverpool –– there is almost always an expectation to win. The Dane started well enough, but deteriorated rapidly with a loss of confidence, and only played 23 times during two years at Anfield.

December 1992 saw Souness once again look to Scandinavia, with the signing of Norwegian international, Stig Inge Bjornebye, for £600,000 from Rosenborg. Bjornebye was never viewed as an outright success at Liverpool, but he was perhaps underrated and undervalued by many. It’s true that his time at the club was very much an up-and-down process, with good seasons followed by bad. But the left-back/left-wing-back served the club well, particularly under Roy Evans, before being sold in 2000 for £300,000, a decent return on a fine, dedicated professional who was 31. In his eight years at the club, he scored four goals in 184 games.

Having failed to get Liverpool into the top five, Souness went all-out in 1993 to find the missing ingredients. It was a summer of big spending and, alas, massive failure. The Reds started the ‘93/94 season in excellent form, winning the first three games, but from that point it all fell away. None of his new signings made the kind of impact he was looking for.

Neil Ruddock was purchased from Spurs for £2.5m in July. Any player who gets ‘self-styled hardman’ put before their name should raise concerns. Perhaps contrary to this image, Ruddock was actually a very fine passer from the back, pinging balls out to the wing with his left foot. An imposing figure, his height made him useful at set-pieces at either end, registering 12 goals in a red shirt in 152 games. But too many times he let himself and the team down. Any time he was injured he returned heavily overweight –– he claims to have piled on the pounds by just looking at food, but in that case, he must have spent every waking moment staring avidly at hamburgers, fries and pies.

More than 40 years after Bill Shankly tried to sign the striker’s father, Nigel Clough was purchased in June for £2.275m. A talented player in the Peter Beardsley mould, the 27-year-old England international however didn’t possess his predecessor’s mobility and sharpness; in essence, he was Beardsley-Lite. Clough started brilliantly, scoring twice on his debut against Sheffield Wednesday and soon added a cheeky flicked goal at QPR. But his form then waned. His best game was against Manchester United at the start of 1994, when the Reds were trailing their bitter rivals 3-0 at Anfield. Clough popped up with two goals, before Ruddock equalised late on. After that, Clough drifted out of the picture, and was eventually sold to Manchester City for £1.5m in 1996, after just 44 games and nine goals.

In September ‘93 Julian Dicks arrived from West Ham, in a deal that saw him valued at £2.5m, but with two players –– David Burrows and Mike Marsh –– exchanged in lieu of cash. The introduction of the feisty 25-year-old Bristolian, as with Ruddock, was designed to add some aggression to the side. But it didn’t really succeed in making Liverpool a tougher proposition. Dicks was a good Premiership player, but he never settled at Anfield, and left for less than half the amount paid for him after just one season.

– Transfer Masterstroke (Rob Jones, see book)

Expensive Folly

Where to start? Dean Saunders, £2.9m? Paul Stewart, £2.3m? Nigel Clough, £2.275m? Julian Dicks, £2.5m? In 2008 money, that’s about £90m of talent, and it amounted to precious little. None of them lasted at the club for more than four years, and none was a regular in the first team for more than a single season. Saunders was the most successful, in terms of performances and recouped fee, while at least Clough had some very good games, even if he was on the whole a failure. Dicks, meanwhile, was steady if unspectacular. Which just leaves Paul Stewart — an expensive mistake if ever there was one. He cost 70% of the English transfer record — over £20m in current terms — and played just 42 times over his five year contract, only to be released for free at the end of it.

One Who Got Away

On November 6th 1991, after Liverpool’s 3-0 victory over Auxerre in the UEFA Cup, Souness met France manager Michel Platini. The French legend told him he had a player who would like to play for Liverpool: Eric Cantona. Souness declined, citing the player’s poor disciplinary record, which included throwing a boot in the face of a team-mate and, on another occasion, throwing the ball at a referee. Within a year Cantona, having helped Leeds win the title, would score a hat-trick in Leeds’ 4-3 Charity Shield win over Souness’ Liverpool, before moving onto even bigger success at Manchester United.

Was it Souness’ biggest mistake? At Manchester United, Cantona proved to be a difficult character on the pitch (although a very successful one at that), but a consummate professional off it, teaching the younger players how to train and look after their bodies (as well as some fine kung-fu moves). It’s easy to see why Souness declined, however. And whereas United were at the stage where they needed one extra spark within a talented and disciplined set-up, Liverpool were nowhere near.

Also with a strong Leeds connection, David Batty was a player Souness had been tracking in 1992, when he ended up going for the more physically imposing Paul Stewart. Leeds parted with Batty a year later, selling him to Dalglish’s Blackburn, where, in 1995, he collected a league winners’ medal.

Budget – Historical Context

Blackburn were building a strong side under Kenny Dalglish, but they would peak once Souness had been replaced by Roy Evans. Arsenal signed Ian Wright in September 1991 for £2.5m, but they were still relying largely on home-grown stars; and anyway, the Gunners were becoming a fading force in the league. Leeds won the 1992 title with some young home-grown talents (David Batty, Gary Speed) and rejects from other clubs (Lee Chapman, John Lukic, Gordon Strachan), before promptly disappearing from the upper echelons of the league.

The big story, of course, was the emergence of the Reds’ bitter rivals Manchester United. While Ryan Giggs had gravitated to the first team from the academy set-up, the side that lost the title at Anfield in May 1992 — Peter Schmeichel, Denis Irwin, Steve Bruce, Mike Phelan, Gary Pallister, Paul Ince, Bryan Robson, Ryan Giggs, Brian McClair, Mark Hughes and Andrei Kanchelskis — still had a very substantial average cost of 45% of the English transfer record. Nine of those players were Ferguson purchases, and clearly he was seriously bankrolled on his way to breaking the club’s 26-year hex.

The side that Souness fielded against United on January 4th 1994, just weeks before resigning — Grobbelaar, Wright, Jones, Ruddock, Dicks, Barnes, Clough, McManaman, Redknapp, Fowler and Rush — cost on average 43.5% of the English transfer record; however, the five purchased by Souness — Wright, Jones, Ruddock, Dicks, and Clough — cost an even higher average of 58%. The Reds came back from 3-0 down to draw the game, but even that great Anfield night couldn’t paper over a myriad cracks.

Conclusion

Graeme Souness cared passionately about bringing success back to Liverpool. But perhaps his all-consuming desire hampered his efforts, making him impatient and causing him to lose both his temper and his perspective.

It took Alex Ferguson four years to simply get United out of the slump that they’d experienced after he arrived, and another three to land a first league title. A case could be made for saying that Liverpool’s new man was simply following the same course. Souness himself used the example of Ferguson, and to this day feels he would have got it right in time: “Liverpool will always be a cloud over me. I know I would have got Liverpool right, but, you know, it took Fergie seven years at Manchester United.” The changes Souness looked to make — related to diet and training — were becoming rife in England by the late ‘90s, but at the start of the decade it was another story. Was he ahead of his time? In that sense it seemed he had the right ideas, but perhaps didn’t implement them properly, while facing resistance from the old guard. Had Walter Smith moved with him, he might have had more luck; as it was, Phil Boersma was not a top-quality coach.

Whatever the validity of his ideas on modernisation, the problem was that Souness’ signings were so unsuccessful and the football often so uninspiring, that there was no leeway. Then there was the selling of his story to the The Sun. Michael Parkinson, the legendary journalist and broadcaster, understood the significance, despite no connection to Liverpool: “What he did was so crass, so insensitive and so plain bloody silly that he must still have been under the influence of the anaesthetic when the pictures were taken.”

Souness might have been correct about eventually getting things right — in time, he might have rectified his mistakes and built a new side. But after three years there were no shoots of optimism — aside from the youngsters he’d inherited, and the purchased Rob Jones — that could be clung to. His subsequent career has shown him to be a fairly decent, capable manager, but a far from exceptional one. And in 1991, exceptional was what Liverpool FC needed.

© Paul Tomkins 2008

“Tomkins not only shows why he is a prolific, talented writer but also cements his status as very knowledgeable and passionate Red. In my opinion this is Tomkins’ best work to date; a thoroughly excellent read.”

Vic Gill, Shanks’ son-in-law and former LFC trainee

“The project that Tomkins has taken on here is highly ambitious: assessing each of Liverpool’s managers since Bill Shankly. He does this in his own irrepressible style of analyzing in detail every area that falls within a manager’s remit. And whilst Tomkins has a talent for such a task, where he excels here is in approaching each manager without any apparent pre-conceived ideas.”

Paul Grech, Squarefootball.net

“A unique analysis of the club’s managers, which is no mean feat given the extensive bibliography of the club… informative … another perspective on the last 50 years at Liverpool.”

Programme & Football Collectable Monthly

****

FourFourTwo